The Scoop

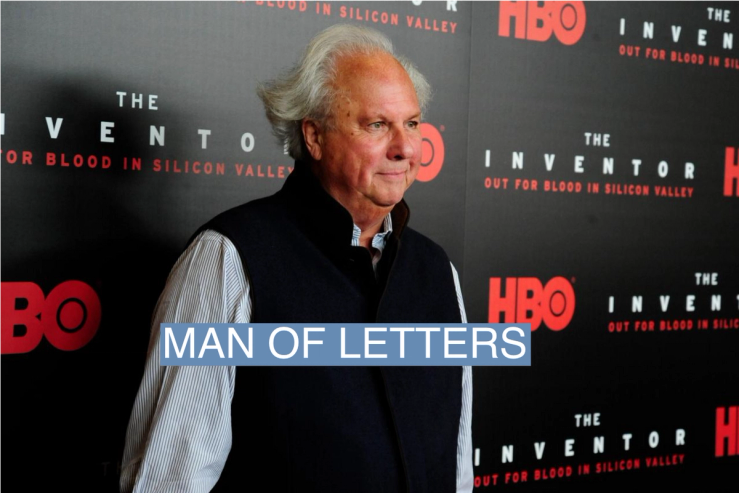

A billionaire roofing family is in talks to buy Air Mail, former Vanity Fair editor Graydon Carter’s effort to drag glossy magazines into the online age.

Standard Industries — whose CEOs, two ex-brothers-in-law named David, are stretching a family business into a wide-ranging financial empire — is in talks to acquire the five-year-old media company for about $50 million, people familiar with the matter said.

Early investors including TPG and RedBird are selling out, and Carter would remain a shareholder under the terms being discussed, which value Air Mail at about four times its 2019 worth.

Representatives for Standard Industries and Air Mail declined to comment.

In this article:

Know More

Carter launched Air Mail, dubbed “The Economist with attitude [for] well-heeled globalists” by the New York Times, after 25 years as the editor of Vanity Fair. Named for the red-and-blue-ringed envelopes that Carter has used for decades as bookmarks, the project promised to bring the magazine’s buzzy, sophisticated style — and its luxury advertisers — to the internet. Standard Industries was an early investor, as was TPG. (Both also backed Puck, another journalistic descendent of Carter’s Vanity Fair, launched by his onetime protege, Jon Kelly.)

Liz’s view

The dire headlines might suggest that media is uninvestable right now, but there’s a lot of money in the world, some of it in unexpected places. Nobody really knows, but by one estimate, family offices manage $6 trillion, more than all hedge funds combined. The largest of them, which invests the $225 billion fortune of the Walmart heirs, would rank among the 100 largest global asset managers if it took outside funds. Most made their money doing one thing very well and are now looking to spread it around, for diversification and for fun.

Standard Industries’s co-CEOs, Davids Millstone and Winter, inherited and built industrial concerns into an operating empire with 20,000 employees and $11 billion of revenue. They are, in some ways, classic media investors: The proprietors of a thriving, unglamorous family business with money to burn, they’ve put about $25 million into a handful of media startups with potential future profits but immediate cachet, including Puck, Malcolm Gladwell’s audio publisher Pushkin, and Cabana, which promises readers “a journey through sophistication, obsessive collecting, colors and fabrics.” (Standard Industries also hired a handful of former Carter deputies, prompting the New York Times to ask, “How many former Vanity Fair employees does it take to build a roof?“)

The company’s origins trace to GAF, a publicly traded roofing company acquired in a 1983 hostile takeover by corporate raider Samuel Heyman, a Milken-backed player in that decade’s dealmaking. Millstone, 46, and Winter, 47, joined the family business by marrying Heyman’s daughters, and Winter brought his own real-estate family fortune into the bargain. In addition to its roofing, trucking, and chimney-duct operations, Standard also runs a roughly $5 billion portfolio of public stocks and venture-backed startups, which tilts toward industrial companies but also holds its media investments.

It’s dabbling in an industry that’s still looking for a workable model. Faustian bargains with social platforms to distribute viral content have failed, and many in the industry are grateful for the deep pockets.

But if advertisers are fickle, the rich can be, too. Recent months have shown the weakness of the benevolent-billionaire model of media ownership, with the Washington Post, Time Magazine, and the Los Angeles Times running through the funds and patience of, respectively, Jeff Bezos, Marc Benioff, and Patrick Soon-Shiong. The Emiratis are trying the same play at the Telegraph.

Those are all legacy media companies, though, with expensive newsrooms to manage and print-first mindsets to outrun. A new generation of billionaires is betting on a new generation of influencers. And the industry’s current woes go down easier when they come with a standing reservation at the Waverly Inn, Carter’s restaurant-salon in lower Manhattan.

Max’s view

Air Mail was an early entrant into a new generation of digital media companies, less focused on reaching a lot of people than on reaching the right ones. With about 50 employees, it has targeted a smaller set of tastemakers driving culture, fashion, art, and politics, and has proceeded on a more careful scale than its traffic-hungry predecessors.

It has found some success catering to that audience, with glossy, top-tier fashion advertisers that otherwise largely avoid digital news. Carter’s last public comments in 2023 put its audience at around 300,000 paid subscribers and said its e-commerce business — which curates lists of bespoke and luxury clothes, accessories, homewares, and other items — accounted for about 15% of its revenue.

It remains to be seen whether more investment can expand the business, and how loyal the subscribers are to Air Mail. Carter has also booked much of the luxury advertising himself. In a world where he is not a part of the publication (he’s 74), can it still get these brands to pay up?

Notable

- “Strangely enough, they’re a very glamorous roofing company,” Graydon Carter told Business Insider in 2021.

- Less robber baron, more drones: The FT on the Davids’ vision of “modern industrialism.”