The News

The venture capital industry and AI are “absolutely in a bubble,” according to one of the biggest technology investors in the world, and it won’t easily be deflated by policymakers.

“I think you just have to wait for it to pop,” Orlando Bravo, founder and managing partner of the $180 billion tech private-equity firm Thoma Bravo, said in an interview. “People are taking enormous risks for small probabilities of enormous returns.”

He said some public stock valuations are still reasonable — “the Magnificent Seven are absolute cash machines” — but warned that if big companies “get way over their skis on huge capex investments and all of a sudden the music stops, or even slows, that would be a big shock to the system.”

Bravo is worth listening to. His firm’s portfolio companies, which sell everything from cybersecurity defense to CFO planning software, are the best window we have into corporate AI spending and whether there is enough appetite to justify Silicon Valley’s huge investments.

Bravo also lived through the dot-com bubble, which scarred a generation of tech investors whose speculation fueled a series of very public flameouts. Today’s gamblers aren’t just venture firms; they are blue-chip companies and twitchy, overleveraged retail investors on a YOLO bender. A tech crash “would not be contained to a given sector or a given community,” he said. “It would just spread. That market cap dwindling would have a big effect all around the economy.”

He spoke with Semafor late last year at his office in Miami, where Thoma Bravo was an early Wall Street gentrifier. Beyond the AI bubble, we talked about where his own software empire is vulnerable, using AI as an excuse for cost cuts, and if his junior employees are secretly using the technology to do their work (and whether he cares).

The View From Orlando Bravo

This conversation has been edited for length and clarity.

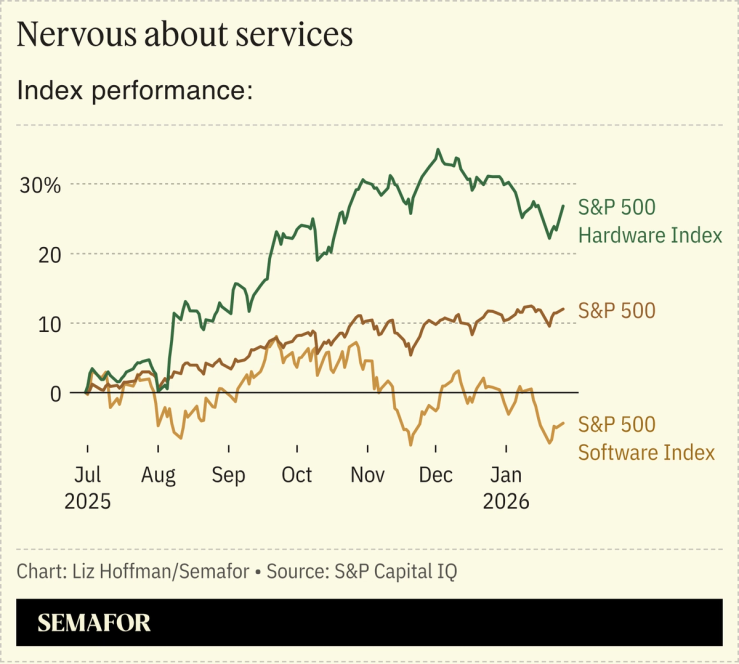

Liz Hoffman: Software is a dirty word in the markets right now. Do you think that’s fair?

Orlando Bravo: What the market is telling us about software valuations is very real. AI for the right software company is an incredible growth opportunity, but they have to do something about it. Now, as many of these companies execute correctly, you will see a resurgence back on those multiples. Think about it this way: Would you rather buy a software company that serves education, or buy a school? Would you rather buy a bank or the company that supplies software to the bank?

But there’s a sense that there will be maybe two or three winners in each software category.

Try one [winner].

Ok, one winner. And my guess is Thoma Bravo owns it. But somebody owns Nos. 2 through 10. One criticism you hear is that a lot of enterprise software is just decent UI sitting on top of pretty undifferentiated code, which can now be written by AI assistants or even by vibe coders, and that when customers figure that out, there’s going to be a massive wipeout.

Software that just summarizes and reports back on basic data is vulnerable. Corporations have found it easier to build that internally. Competition is not only what your competitor is doing, but what your customer can do. But I want to be careful with these general statements. There’s a lot more that goes into these applications than the technical aspect.

When we bought our first software deal, Prophet21, [in 2003], the main risk was that Microsoft was consolidating that industry. Believe me, Microsoft could come up with a product 20 times better than the little company we were buying. But Prophet21 knew the distribution business. They knew what tile distributors and electrical companies needed. This is still as much a service industry as a technical one.

We have the best office-of-the-CFO planning company there is by far, Anaplan. They know FP&A. They know the language of the business. There’s a lot of learning that goes into that, so I wouldn’t discount the value of a standardized way of doing a certain process and doing it right.

So why is Salesforce getting hammered right now?

Well, hold on. Some of these companies have gotten hit in the last year because, again, there’s more execution risk. They have to prove things that they didn’t have to prove before. So maybe the discount rate is a little higher, but they’re still trading at very good multiples.

You lived through the dot-com bubble. Do you think we’re in a bubble now?

AI is absolutely in a bubble. It doesn’t make any sense. People are taking enormous risks for small probabilities of enormous returns. And at the end of the day, a company is worth a multiple of its net earnings or net free cash flow. And the kind of earnings that you have to produce to make 3x or more return — while suffering no dilution from future rounds, including an IPO — is enormous. And there’s just not that many people in the world that can do that. Some will stay in the business, and some won’t.

Is there a way to deflate that bubble? Alan Greenspan didn’t think so.

I think you just have to wait for it to pop. I wouldn’t necessarily translate the venture capital bubble into a public market one. Some [stock prices] are reasonable out there. The Magnificent Seven are absolute machines. But if people get way over their skis on huge capex investments and all of a sudden the music stops, or even slows, that would be a big shock to the system.

The other thing to ask is whether investors will continue holding [Big Tech stocks and bonds] versus the infinite world of opportunities they have. Should they have more infrastructure? Should they just earn 11% in private credit? These companies still need the support of their shareholders. That’s another risk element if that big money says, ‘I get it, but I’ll see you in two years when this works.’

The dot-com crash was painful but didn’t spill over into an economy-wide event. Would this one be worse?

It would be bad. Now you have the big money, these enormous corporations, heavily invested in it. It would not be contained to a given sector or a given community. It would just spread through, especially if one of the very large players gets hit by a big surprise. That market cap dwindling would have a big effect all around the economy.

I want to pivot to the investing business broadly. There are tens of thousands of alternative-asset managers out there right now. What do you think that number is in five years?

Private equity is going through a shakeout. The industry bought a lot of things for very high prices. There’s not enough exits, and in many cases people have run the companies for cash today instead of investing in the future, which is coming to light now [as hold times increase]. Have you been making the right decisions for the business, or did you think that you could just cut costs, get the margins higher, and make money? But I don’t see big consolidation coming. That’s very difficult to do.

Thoma Bravo has so far sat out the push into retail as Blackstone, KKR, and others have piled in. Why?

We’re cautious and we’re open-minded about it. The added pressure of producing great and consistent, but also now short-term and consistent returns [that retail investors want], is hard. As it relates to those large managers, I can’t comment on the specifics, but it’s hard to bet against them because they’re so good.

We are not yet seeing that money circulating. It’s not like our phones are ringing off the hook with [Blackstone or KKR saying] “I just have another 10 billion here. What can we do together?” Maybe they have different strategies for it. But the sector that we cover is the largest by far in private equity — almost 40% of the buyout business is software — and we’re not seeing these flows.

Let’s talk about junior talent and AI. AI can create a cash-flow model in seconds — don’t you think they’re all secretly using it?

Probably. But you catch that when you go to an analytical approach to decision-making. [You ask them] “why does the backlog in this company continue to build? Is there something going on with the business?” You know pretty quickly whether people are focused on the right things. I think [AI] can be additive. It’s not a substitute to understanding how a business works.

There’s no substitute to the grind. But young people go quicker to scraping or finding information in an efficient way that is not necessarily calling people on the phone. Leaders have to adjust to that. Does that mean that we change the way we hire? No.

Will there be PE agents cranking on due diligence while your analysts are off taking clients to dinner?

This moment is inspiring people to think about how they can automate their businesses more. Look at a lot of the cost cutting that’s happening across corporations. How much of that is due to AI or agentic solutions versus old-fashioned “I can take out 15% of costs”?

You think it’s the latter?

A thousand percent, yes, because the investments in the corporate world in AI are not big enough yet to produce all this efficiency. [Recent layoffs are] not directly related to the technology. AI is a cover to become much more efficient.

We recently had a panel at our AI conference of our biggest customers, non-software companies. There were five of them, representing $1.5 trillion in market cap and a million employees. We asked, where do you want to be in five years from a revenue and an employee standpoint? All of them said they want their employee headcount to be the same and revenue to be two to two-and-half times higher.

Thoma Bravo has largely stuck to its knitting in buyouts. Would you ever take it public or expand beyond software?

We’re going to be much bigger in five years, organically. But we keep our business simple. We have around 220 people for almost $200 billion in assets. We don’t need to be hiring a lot because we don’t have a lot of turnover. We don’t have to be training all these new people because our people stay and they have a path towards future leadership. All of our time is spent on: get the deal, improve the deal, sell the deal. I don’t have to worry about getting my stock price up next quarter. No, we’re not going to go public.