The Scene

Private equity firms that were once Wall Street’s disruptors have turned into its establishment, and are turning to a solution they know well: deal-making.

In the latest move, General Atlantic, known for taking stakes in fast-growing private companies, is buying Actis, which owns telecom towers in the Balkans and data centers in Chile. BlackRock, diving into alternative investments after years of false starts, is skipping right over pure-play private equity with its $12.5 billion acquisition of GIP, an infrastructure giant. That follows TPG’s deal last fall for credit and real-estate specialist Angelo Gordon.

Private equity has outrun both its roots and its name. Faster-growing corners of investing, like credit and infrastructure, and faster-growing regions, like the Middle East and Asia, are pushing Wall Street and City veterans beyond their LBO origins. So are their customers: Pension funds want a handful of investing superstores rather than a sea of boutiques, and are offering bigger checks to fewer managers.

“We don’t think of private-equity as being a mature industry but it is,” said Daniel Lavon-Krein, a partner at Kirkland & Ellis. “They’re the incumbents, and have all the pressures and incentives that come with that.”

Of 116 M&A deals struck by big alternative asset managers in recent years, one-third have moved them into credit, real estate, or other types of investing, according to data from Bain & Co. One-fifth have added a new geography, mostly in Asia.

The CEO of Partners Group predicts that 11,000 private-equity firms will whittle, by consolidation or evaporation, to as few as 100 “next generation platforms” over the next decade. The CEO of EQT, a European giant on a deal-making spree of its own, sees maybe a dozen global firms and a handful of niche players. “The rest,” Christian Sinding said, “will be stuck in the middle.”

In this article:

Liz’s view

BlackRock, which dominates the world of low-fee, brown-shoe ETFs, has spent years plotting its move into the high-fee, Italian-loafer world of private investing. By choosing GIP as its chassis over a more traditional private-equity firm, Larry Fink essentially dismissed the pure-play model.

He and General Atlantic’s Bill Ford are correctly calling the top of pure-play private equity — the basic model of buying a company, mostly with borrowed money, making some operational improvements, and selling it for a profit.

It’s not just that debt, the rocket fuel of any buyout, suddenly got expensive, although that makes the end of this era sharper than it might otherwise be. Today’s companies are more efficient than the sleepy giants targeted by private equity’s founding buccaneers, so there’s less fat to cut. “Exclusive” deal access and insider deals have been replaced by open-air auctions that drive prices up and returns down. Pension funds want to deal with fewer managers, and pay each of them less. Fee-free “coinvest” rights are table stakes.

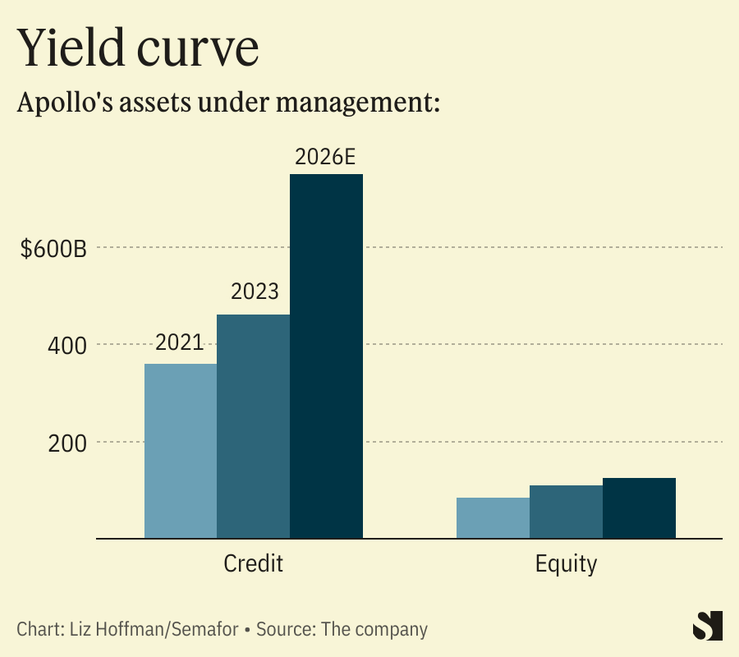

“In the equity business, this year has really marked the end of an era,” Apollo CEO Marc Rowan said last spring. Apollo saw this coming: It now makes two-thirds of its money offering retirement products and is growing its credit assets twice as quickly as it’s growing traditional equity assets.

A few pure-play holdouts are betting that they’re good enough at their knitting to stick to it: Vista (software buyouts), Warburg Pincus (financial services), and L Catterton (retail). Those three probably are. But I wouldn’t want to be the next rung down: “Monolines with average returns are in big trouble,” Citigroup investment-banking executive Anthony Diamandakis told me.

Room for Disagreement

Expanding simply for the sake of doing so created the conglomerates of the 1980s and 1990s that the private-equity industry busted up.

The shift toward financial supermarkets has also been a mixed bag for big banks, as each has tried to fill in their missing pieces with varying degrees of success. Goldman Sachs lost billions trying to build a consumer bank. Bank of America can’t quite turn its $3 trillion balance sheet into Wall Street success. Citi is now trying, again, in wealth management.

Notable

- Buyout shops are starting the year with For Sale signs for their portfolio companies, according to Bloomberg.