The Facts

Mass migration is destabilizing countries across the world. In the Netherlands, anti-immigrant politics drove the shock victory of the far-right Freedom Party. In the United States, Donald Trump’s Republicans continue to whip up fears around border security. Anti-immigrant vigilantes in South Africa recently registered as a political party.

These trends are not just the result of political opportunism or social media. They are connected to the historic movement of people across the world, driven by chronic poverty, corruption, conflict and, more recently, the climate crisis.

These challenges cannot be left to populist politicians. We need to take a holistic approach to address global migration, starting with our traditional framework for international development. The best place to limit migration is not in the middle of the Mediterranean or the English Channel or the Rio Grande. It is in the home countries that so many migrants are so desperate to leave. That means broadening the target of economic development beyond the bottom of the pyramid.

Herbert’s view

If you want to see more economic opportunities across the world, you need to encourage the growth of a stable middle class, developing skills locally. That can only happen by investing in higher education across the developing world. However, as UNESCO recently reported in Africa, access to universities and colleges remains stubbornly low even as enrollment is rising. The system is starved of funding at a time when the population is rapidly growing.

Instead of growing our economies through higher education, we are losing some of our brightest prospects in large numbers – undermining both sides of this brain drain. The countries that are struggling with the politics of immigration are often the ones that exploit the skilled workforces of the developing world.

Boosting Africa’s economies, and improving global stability, does not necessarily require a large increase in international aid. But it does require a change in mindset. It is time to stop seeing Africa as a continent where resources and people can be exploited. After all, there is little difference between mining the natural resources of a continent and stealing away some of its best people. Neither extraction is replenished.

To better understand this point, and the paradigm shift required, we must scrutinize the current status quo. Anti-immigrant politicians and commentators wonder out loud why so many of those on small boats want to travel to the UK, rather than staying in the EU. They could find one of the answers in their own national policy.

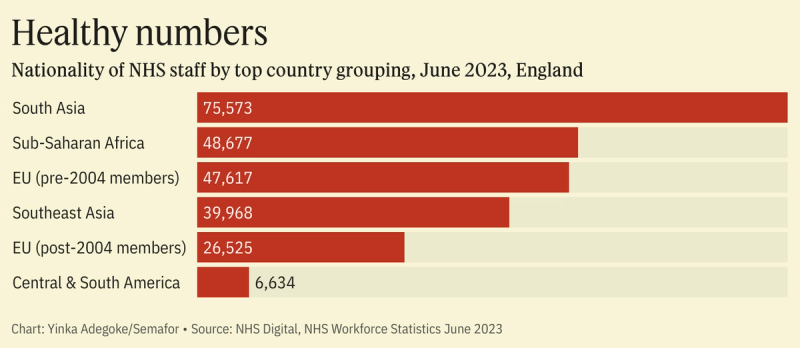

British institutions see African talent and cash as a growing source of low-cost expertise and profit. International students contributed an annual £41.9 billion ($53.4 billion) to the British economy after the pandemic, a rise of one third from the year preceding COVID-19. There are some 50,000 African nationals working in the UK’s National Health Service, most of them from countries in sub-Saharan Africa. That’s more than double the number of a decade ago.

You cannot systematically recruit the best and brightest from Africa, selling a vision of British heaven, but slam the door shut to those at the lower end of the economy with less obvious talents.

The British High Commissioner to Nigeria recently revealed that the number of Nigerian students at British universities increased fivefold in the last three years. International students now represent a fifth of the total income of British universities, and close to half of those students come from India, China and Nigeria. Many of those students do not return home.

Typically, across the EU and the UK, more than a third of them remain in the country where they study. Even more important than the flow of migrants, policymakers need to ask themselves what impact they are having on African countries when they hollow out our middle-class, technical expertise and the next generation of leaders.

Development is too often reduced to the most basic, essential level, rather than seen as an economic continuum. The World Bank’s Human Capital Project recognizes that investing in people is key to sustainable and inclusive growth. But it measures these investments through the lens of extreme poverty — especially nutrition, healthcare and basic education. These are understandable priorities.

However, you cannot solve chronic poverty or mass migration through international aid alone. For that, you need economic growth and good governance — and those require business leadership, a growing middle class, and a strong civil society. All of those are undermined by the systemic recruitment of Africa’s skilled workers and best students.

Instead of plundering talent and siphoning off precious foreign exchange for education fees, Western governments, businesses, and institutions should seek African partners in developing our professional class and our next generation of leaders.

It is not a mark of success to extract African funds to support your universities, or African nurses to support your hospitals. It is instead a failure to understand how the West is undermining its own policies and politics with a worldview that remains contorted by colonial history.

Herbert Wigwe is the founder of Wigwe University and the group CEO of Access Holdings