The News

African countries unable to borrow internationally risk amassing domestic debts that could “significantly blow up,” a senior African Development Bank economist has warned.

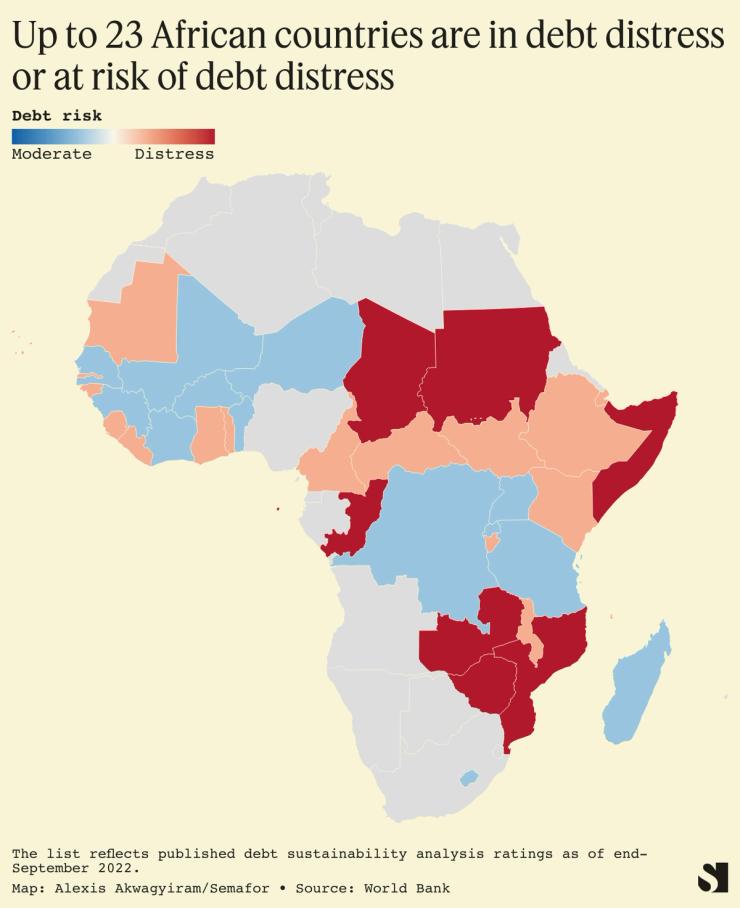

Nearly half of Africa’s countries face difficulties making their debt repayments, according to figures compiled by the World Bank and International Monetary Fund. Eight countries are in debt distress — meaning they are unable to fulfill their financial obligations — and 15 others are at high risk of falling into that category. As countries struggle, their creditworthiness plummets and they find it difficult to borrow from global markets.

In December, Ghana launched a domestic debt exchange and said it would default on nearly all of its $28.4 billion of external debts. It became the second African country to default since the start of the pandemic, following Zambia in late 2020. Other countries struggling to service their debts include Congo Brazzaville, Mozambique, and Zimbabwe.

Anthony Simpasa, who leads AfDB’s debt sustainability division, said there is a danger that some nations locked out of international capital markets would ramp up domestic borrowing, which “could significantly blow up the country’s debt situation.”

“The challenge is that borrowing domestically would trigger a rise in domestic interest rates, and that would also wipe out private sector investment in those countries,” Simpasa said, adding that it was important not to focus solely on foreign debt

Simpasa said the debt problems faced by many African countries could spill over into 2024. He said countries struggling to meet their financial obligations should work with lenders to restructure their debts, and urged more to do so under the G20 Common Framework. The program was set up to enable the swift reworking of debt.

In this article:

Alexis’s view

The idea that African countries must avoid loading up on domestic debt is a point that is often overlooked because analysts tend to focus on external borrowing. But it matters, and Simpasa’s point provides a well-rounded picture of the potential pitfalls faced by several countries.

The options for reworked debt are tricky too. The Common Framework has been widely criticized for being a slow process. Last week Reuters reported that Ghana planned to request debt relief via the program so long as it received assurances that negotiations could be expedited.

Chad, Ethiopia and Zambia signed up to the program in early 2021. Chad reached a deal with creditors in November but Zambia is still in talks and Ethiopia’s discussions were delayed by its civil war.

The debt problem matters because of the impact on people’s lives. Terms like “distress”, “Eurobonds” and “haircut” gloss over the true significance of the issue: the human cost.

The more money a country uses to service its debts, the less it has to spend on education, health and social services to mitigate the impact of higher food costs on the most vulnerable citizens. It also means a government can’t set up the nation for future economic growth by investing in social initiatives to develop a skilled workforce.

Room for Disagreement

There are African countries that are bucking the trend of debt problems. Ratings agency Fitch, in a report, said some African nations “enter 2023 in a more robust position, including those that have benefited from higher commodity prices.” It cited Angola, one of the continent’s top oil exporters, as an example.

Simpasa said higher oil and gas prices had enabled some countries “to accumulate a little bit more in a windfall that is helping them to narrow their fiscal deficits.”

The View From London

Charlie Robertson, global chief economist at Renaissance Capital, argues that most African governments aren’t focusing on a key factor in determining public debt levels — family size.

A country’s fertility rate is the average number of children women in the nation give birth to. Many western countries have fertility rates far lower than the average of 2.1 children demographers say is needed for a population to grow, but most African nations have fertility rates of 3 or above. “Every country with a fertility rate above three children on average is at risk of default,” Robertson told Semafor.

He said 90% of defaults occur in countries with high fertility rates. That, said the economist, is because people have too many children to save, leaving bank deposits low and interest rates high. As a result, governments in those nations seek foreign loans which have lower interest rates than other forms of borrowing, leaving them vulnerable when their currencies weaken.