The News

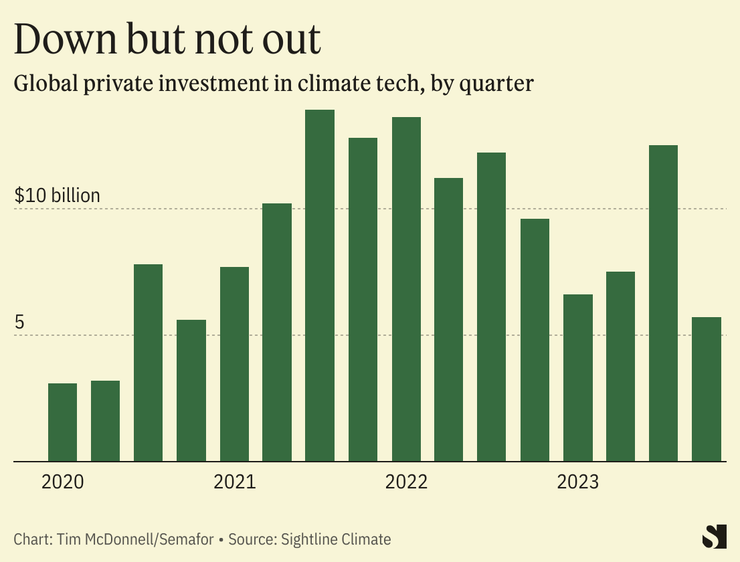

Just at the moment when a new generation of technologies needs to scale up to decarbonize the global economy, private investors are slamming on the brakes. The last quarter of 2023 was the worst for global climate-tech fundraising since 2020.

Climate-tech companies raised a total of $32 billion in 2023, down 31% from the previous year, according to data published today by intelligence firm Sightline Climate. There were also fewer deals overall, the first annual dip since 2020. The size of deals and their total number shrank or stagnated across all stages of the fundraising cycle, from seed to growth, keeping pace with a broader contraction across startup fundraising more broadly as investors confronted rising interest rates and the possibility of a recession. 2024 looks like it could hold more of the same.

In this article:

Tim’s view

Climate tech is stuck in second gear, the Sightline data suggests, with investors in a kind of holding pattern while they wait both for overall economic conditions to brighten and for bets from the last few years to pay off. It’s no surprise that they are playing it safe, given how many got burned in the clean-tech bust of the 2010s. The contraction in early-stage deals is also a sign that fewer entrepreneurs are willing to roll the dice on new ventures. But time is also running short to bend the global emissions curve; breaking through will require more investors to be willing to take first-mover risk, and require more mature companies to prove they were worth the investment.

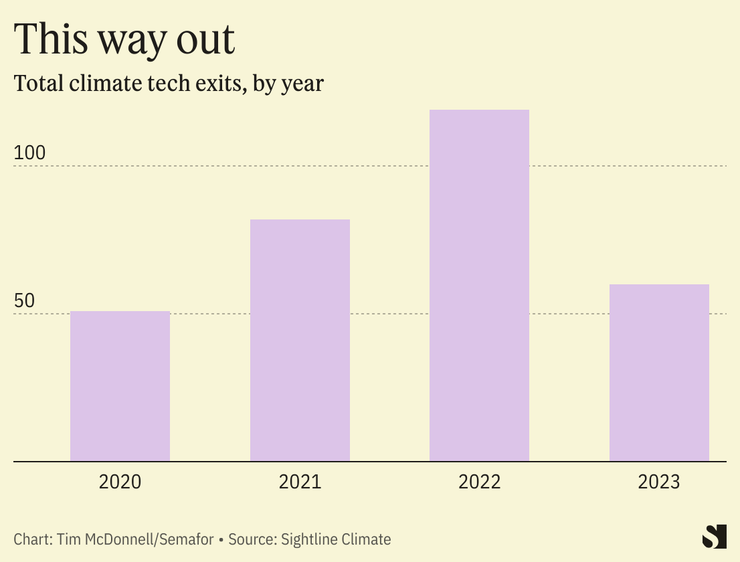

The rate of companies that “graduate” from one fundraising level to another has been steadily shrinking since early 2022, as firms choose instead to tread water and try to lock down their product and place in the market rather than grow too quickly. That leaves less capital available for new ventures, which helps explain why Seed and Series A funding tapered off in 2023 for the first time since 2020. And it means that fewer climate-tech companies are reaching an exit — either going public or being acquired — which leaves big investors with fewer winnings to put back into circulation.

“The big conversation people are having is about what climate-tech exits look like, but the cohort is really early so it’s really hard to say,” Sophie Purdom, managing partner of VC firm Planeteer Capital, told me.

There’s little appetite to take climate-tech companies public; several that did so in the last few years, like electric bus maker Proterra, ended up flaming out quickly. With that off the table, the most promising path forward is an acquisition, most likely by a large industrial or energy company, including oil and gas majors, that are under enormous pressure to decarbonize and desperate for readymade solutions. Acquisitions could ramp up this year, especially of startups that are out of VC runway and willing to go on the market for cheap.

But not every company will reach an exit. Climate tech is likely in for a bit of healthy contraction, Purdom said: “A lot of businesses will shutter this year, but that’s totally fine. The really bad scenario would be if there’s a big pop rather than the air gradually being let out of the tire.”

Until the winners from the current generation of startups are more clear, the VC funding pipeline may continue to narrow. But 2024 could deliver some answers, and will be a year when some more mature companies get a chance to prove their mettle by signing or delivering on their first large customer contracts or breaking ground on first-of-a-kind factories.

“2024 is when the rubber starts to meet the road,” said Clay Dumas, founding partner at Lowercarbon Capital. “Some early winners will be revealed, and that will set off even more investment and new company formation.”

Room for Disagreement

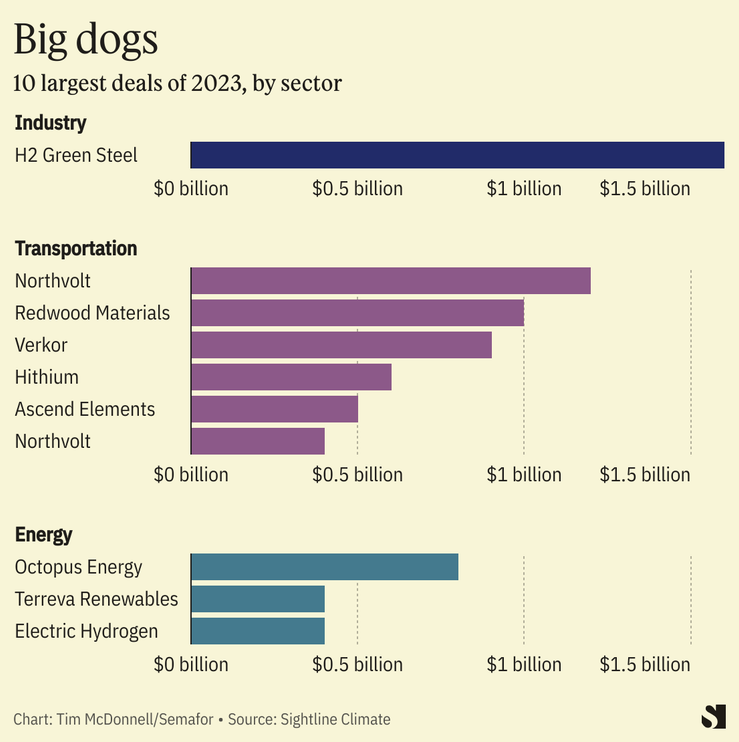

There were some mega deals this year, mostly in the electric-vehicle battery sector, that were largely built on vast injections of public funding they locked down in previous years. And since there were some chunky federal funding rounds announced in 2023 — for example, $1.2 billion from the U.S. Department of Energy for direct air capture facilities — there’s reason to hope more private funding will follow over the coming year.

Another key question is whether interest rates stabilize. If they do, “I believe that, yes, the contraction will turn around,” said Scott Jacobs, CEO of infrastructure investment firm Generate Capital. Jacobs told me he’s bullish on emerging technologies like carbon capture and hydrogen, but especially on boring-but-booming solar.

The View From Wall Street

Climate tech funding is almost exclusively channeled to emissions-reduction ventures; climate impact adaption technologies are still usually ignored. That might change this year, said Christian Hernandez, a partner at climate-focused VC firm 2150, with special interest from big financial institutions that have the most to lose if assets they own or insure get hit by a flood or wildfire: “There’s a lot more chatter on adaptation, and it will be banks and insurers who drive it because they have a large pool of exposure.”