Ben’s view

It’s a funny time to be optimistic about global media. But we wouldn’t have started Semafor if we weren’t. The very fact that you’re reading this, in my addled start-up brain, confirms my belief that there’s enormous interest in new forms and new platforms for journalism.

And yet when I asked Friday on Twitter, Post, and Mastodon if anyone was feeling optimistic, the good cheer seemed to outweigh the eyerolls. The same has been true in my conversations with media executives, like Vox’s Jim Bankoff, who texted me below about the long-term benefits of platforms giving up on news.

The big reason for optimism is that the media monoculture is over. The 2010s were a decade in which, by the end, only one thing worked for much of news and entertainment: Social media, and its instruction to hold a mirror to your audience, telling them what they wanted to hear and showing them what they wanted to see.

Now, if you look around, you’ll see a varied world of small and medium-sized projects that are just working with audiences. These green shoots range from bespoke print magazines to ambitious local online newsrooms to TikTok accounts raising their journalism games. I’ve even heard some optimism about the rebirth of higher-quality prose, and the hope that GPT-3 can at least do away with some of the most tragic journalese. The quest to turn movies into events, from IMAX to Alamo, continues. We’ll see.

But before I get all starry-eyed, let me acknowledge the two big reasons that 2023 will be a hard year:

- The economy is already cooling advertising markets, and a recession would hit the media business broadly, with impact from producing layoffs to canceled productions.

- The large-scale subscription business is capping out for natural reasons: The growing cost of reaching the next customer, the difficulty of keeping the current ones. From Netflix to the Washington Post to medium-size sports Substacks, subscriptions remain a solid business — but the ceilings seem to be a little lower than anyone hoped.

So 2023 is looking like a tough year for the economics of big media. But the shifting internet, and audiences who have grown sophisticated in their digital tastes, also mean it’s a moment of change and opportunity.

Here are my non-comprehensive, slightly eccentric reasons for optimism this New Year’s Day:

1. A new generation of local news is coming of age

The real collapse of American news has been on the local level, with the giant chains like Gannett that gobbled up the industry decades ago continuing to bleed jobs. But an increasing number of readers are seeing local outlets, from quirky newsletters to well-funded non-profit and for-profit ventures, come of age.

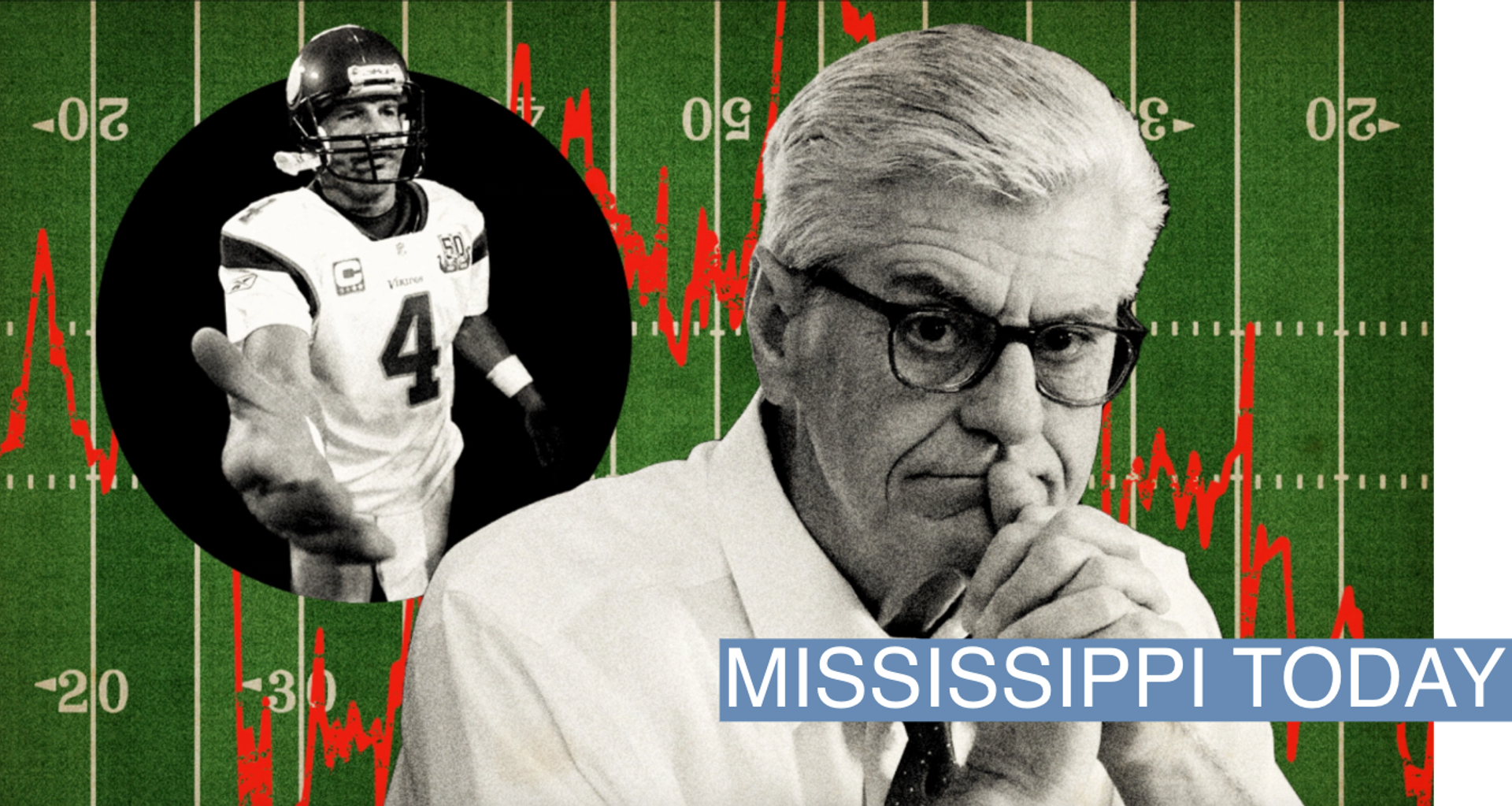

The most spectacular in 2022 was Mississippi Today, which broke one of the year’s truly jaw-dropping stories, revealing the roles of former Gov. Phil Bryant and NFL legend Brett Favre in the state’s diverting federal funds intended for the poor to athletic facilities at Favre’s alma mater.

“We are serving numerous roles in this state that no one else can or will, and we take that responsibility very seriously,” editor-in-chief Adam Ganucheau told me in an email. “It’s so damn cool to see such incredible journalism happening in nonprofit newsrooms across the South and the nation.”

2. Apple has figured out how to make TV

The much-mocked (including by me!) Apple Originals studio faces some rather serious restrictions: The company seems to require 11 Apple devices in every Ted Lasso scene and caved to Tim Cook’s disdain for a Gawker show, not to mention imposing a dead-serious ban on angering the Chinese government.

And yet, against all odds, Apple has picked up where the HBO- and Netflix-led Golden Age of TV let off, with shows like Ted Lasso, The Morning Show, and Severance cutting through the cultural noise. Now while most studios are cutting and canceling, Apple is buying ambitious new shows.

3. China Substacks are proliferating

Beijing’s censorship and the COVID lockdown can make it hard for English-language readers to follow news from China. You find yourself swinging between occasional revelatory investigations from western news organizations and random, out-of-context social media posts.

But the newsletter boom has served consumers of China news particularly well, and interested readers can find themselves in thoughtful conversation with academics, journalists, and bloggers whose perspectives range from the Washington hard line to writers at Chinese state institutions.

These are mostly one-person shows, and the biggest comes from one of the original Substackers, the longtime China correspondent Bill Bishop. But together they’ve brought a daily cadence of conversation and a set of obsessions from food to artificial intelligence into a beat whose substance is often solely geopolitical and whose rhythm has sometimes eluded more conventional journalism.

Favorite newsletters for my Semafor colleagues Prashant Rao and Louise Matsakis and me include: Chaoyang Trap, China Talk, Discourse Power, Pekingnology, ChinAI, Following the Yuan, Siming Shan, Ginger River Review, Far & Near, Concrete Avalanche, Crossing the River by Feeling the Stones, The Cleaver and the Butterfly, and MacroPolo Econ. Two others of note: Tracking People’s Daily and What’s on Weibo offer glimpses into the official and unofficial-but-still-censored internal Chinese conversation.

4. Crypto journalism grows skeptical

The first wave of crypto media in the 2010s was distinguished by its credulity, at best, and at worst participation in ICO scams. But the latest crypto boom produced professional journalism whose premise (cyrpto!) you can question, but whose reporters were mostly trying to get to the truth. They broke many of the biggest stories of the meltdown.

Big crypto outlets are going to have a tough 2023, with more cuts and consolidation. But crypto journalists are thinking about how to take their skills and their audiences outside the fast-cooling crypto space. Some of that means trying to move into straight financial journalism: Covering macro-economic news “basically serves as a hedge for us against crypto bear markets,” Jason Yanowitz, the co-founder of Blockworks, told me.

“The stuff that we are mostly concerned with are frauds or scams,” said Orson Newstat, who co-hosts the podcast Crypto Critics’ Corner. “We want to expand into other areas of frauds or scams or other weird financial shenanigans.”

5. There’s (some) hope for Twitter

Twitter’s new hostility to legacy media is pushing journalists, and a lot of the hard news and information they delivered, away from the platform. Some of what is replacing it is anti-vaccine crankery and ill-informed threads by amateur historians, and the dream of a single trusted social platform for news has faded.

But the chaotic platform is also creating new space for genuinely alternative voices after a decade in which social media often enforced journalistic consensus and groupthink.

“There’s a shift back toward populism and alternative voices, and that means a lot of things — but maybe there’s space for truly independent transgressive views,” said Lee Fang, an investigative reporter at The Intercept, who, to be fair, didn’t sound all that optimistic.

6. Return of the aggregators

And at least somebody is having fun, Max Tani writes:

In 2022, newsletters got nichier, podcasts got longer, and my monthly bill for paywalled news got bigger. So I find myself increasingly grateful for the success of some of digital media’s least respected players: The aggregators.

These are Twitter accounts like @FilmUpdates, for Hollywood news, or @PopCrave, which obsessively recirculates celebrity social media accounts. There’s @NBACentral and @TheHoopCentral for every bit of gossip, trade speculation, or shade from anonymous league executives.

The aggregators aren’t doing anything novel in repackaging public news quickly and concisely. But they do project a palpable sense that the people running the accounts actually like what they’re doing. Jacob Fisher, the 21-year-old digital marketing student who runs @DiscussingFilm, told GQ earlier this year that he shares 40-50 tweets a day to the account’s 770k followers “not because I can’t find anyone to do them but because, quite frankly, I really enjoy doing it.”

— Max Tani