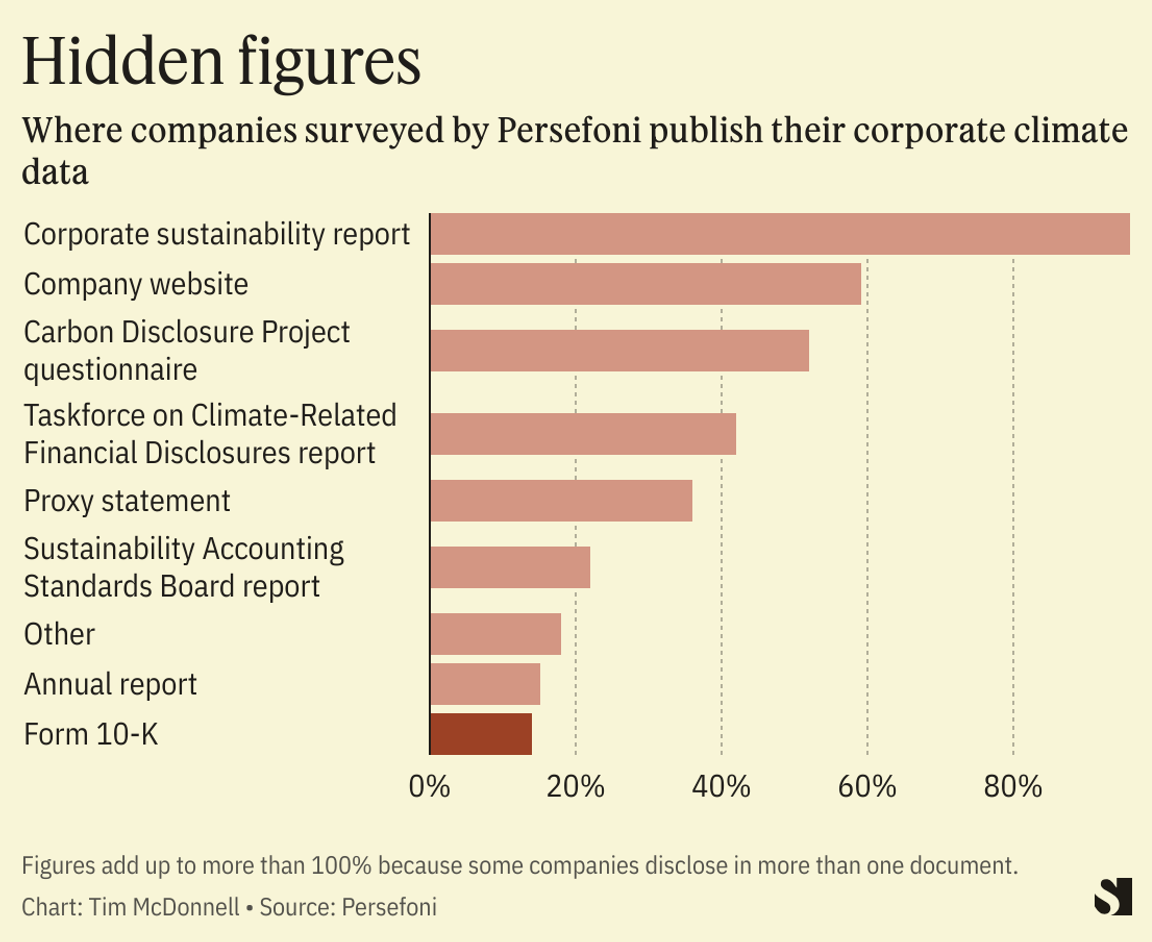

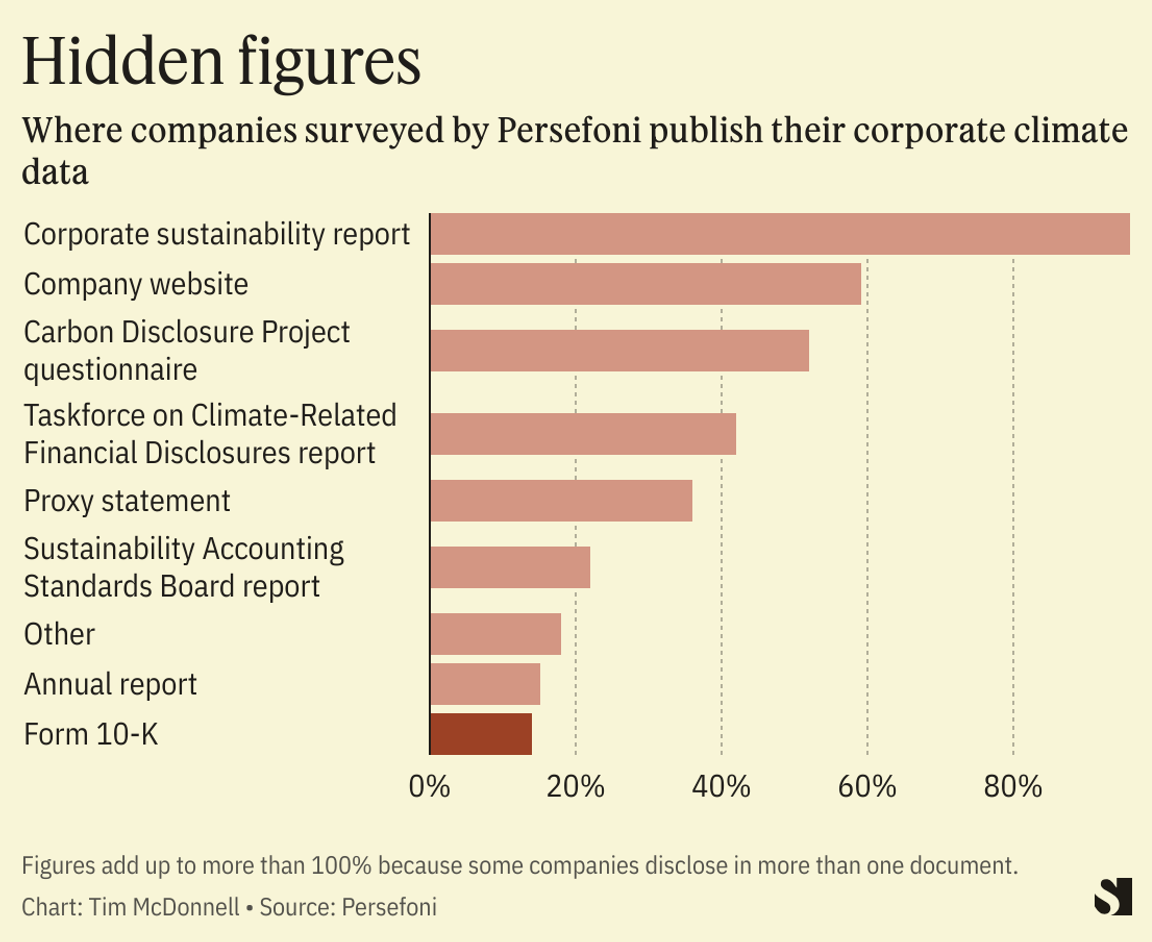

JOHN G. MABANGLO/Pool via REUTERS JOHN G. MABANGLO/Pool via REUTERSBy Tim McDonnell THE NEWS Companies — big and small — won’t be able to put off disclosing their full carbon footprints much longer. The European Union recently finalized standards for corporate climate disclosures which will take effect in January and eventually apply to about 50,000 companies, including an estimated 10,000 based in the United States. The U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission is expected to finalize its own rules next month. And California might beat them both to the punch: State legislators are expected next week to approve a pair of climate disclosure bills that go even further than the SEC on key points. “The train has left the station,” said Mike Wallace, chief decarbonization officer of the carbon accounting firm Persefoni. TIM’S VIEW Although a growing number of corporations are measuring their carbon footprints for the first time, many have strongly resisted being forced to publish the results in their financial statements, pressuring the SEC and EU regulators to water down their draft disclosure rules. There are two main sticking points: Scope 3 emissions, and the cost of future climate impacts.  Emma Roshan Emma RoshanCompanies are concerned that being forced to disclose their Scope 3 emissions — which include upstream emissions from suppliers and downstream emissions from customers’ use of a company’s products — is an imprecise, tedious, and expensive process. Many climate economists, on the other hand, insist that measuring Scope 3 is getting easier all the time, and that especially for energy companies and other big emitters it’s essential. The EU regulations let companies off the hook for Scope 3 if they can prove they’re not “material” to investors — a vague and potentially subjective definition that Tsvetelina Kuzmanova, senior policy advisor at the think tank E3G, said will muddy the waters and pass the buck to a cottage industry of carbon-auditing firms. “With the justification of reducing the regulatory burden on the companies, they’re actually just creating more uncertainty,” Kuzmanova said. “We’re looking at a mess here.” A draft version of the SEC rules took a similar approach to Scope 3; the difficulty of how to handle those emissions with a minimum risk of lawsuits — either from irate environmentalists or irate corporate lawyers — has been one of the main issues holding up the final version of the rules. The California regulations, which are expected to pass a vote in the state Assembly by next week with the backing of prominent companies including Adobe and Microsoft, would require universal Scope 3 disclosure. Climate impact risk — which the EU, SEC, and California regulations also require to varying degrees — is potentially even more complicated. Imagine a multinational firm with warehouses scattered around the world. Putting a specific dollar figure on climate-related damage to those warehouses in a given year is hard enough. Projecting those to the future requires companies to practice a kind of hyperlocal climate modeling that is challenging even for climate scientists. Notwithstanding these obstacles, a growing number of companies are voluntarily disclosing climate data, especially on emissions. A survey by Persefoni in August of 90 large U.S. companies found that 73% report Scope 1 and 2 emissions, and 26% report Scope 3. The reason, Wallace said, is that everyone is already demanding it: Shareholders, government procurement contracts, customers, financiers, other businesses in a company’s supply chain, etc. “It doesn’t matter what happens with these regulations,” he said. “You’re going to get questions about your carbon footprint.” The problem, as expressed by influential lobbying groups like the Business Roundtable — which is meeting next week in Washington, and which made a splashy commitment to sustainability in 2019 — is making those disclosures mandatory. The Persefoni survey shows most companies that do disclose are putting the data in places where it’s unlikely to draw much scrutiny or make them liable to fraud or greenwashing charges. Only 14% reported the data in their 10-K financial statements.  Legal risk isn’t the only concern businesses have: Firm-level emissions data is also a key ingredient for future carbon taxes and emissions allowances. “Make no mistake,” said David Smith, an environmental attorney at the California firm Manatt, Phelps & Phillips. “This will be the baseline from which further reductions are mandated.” |