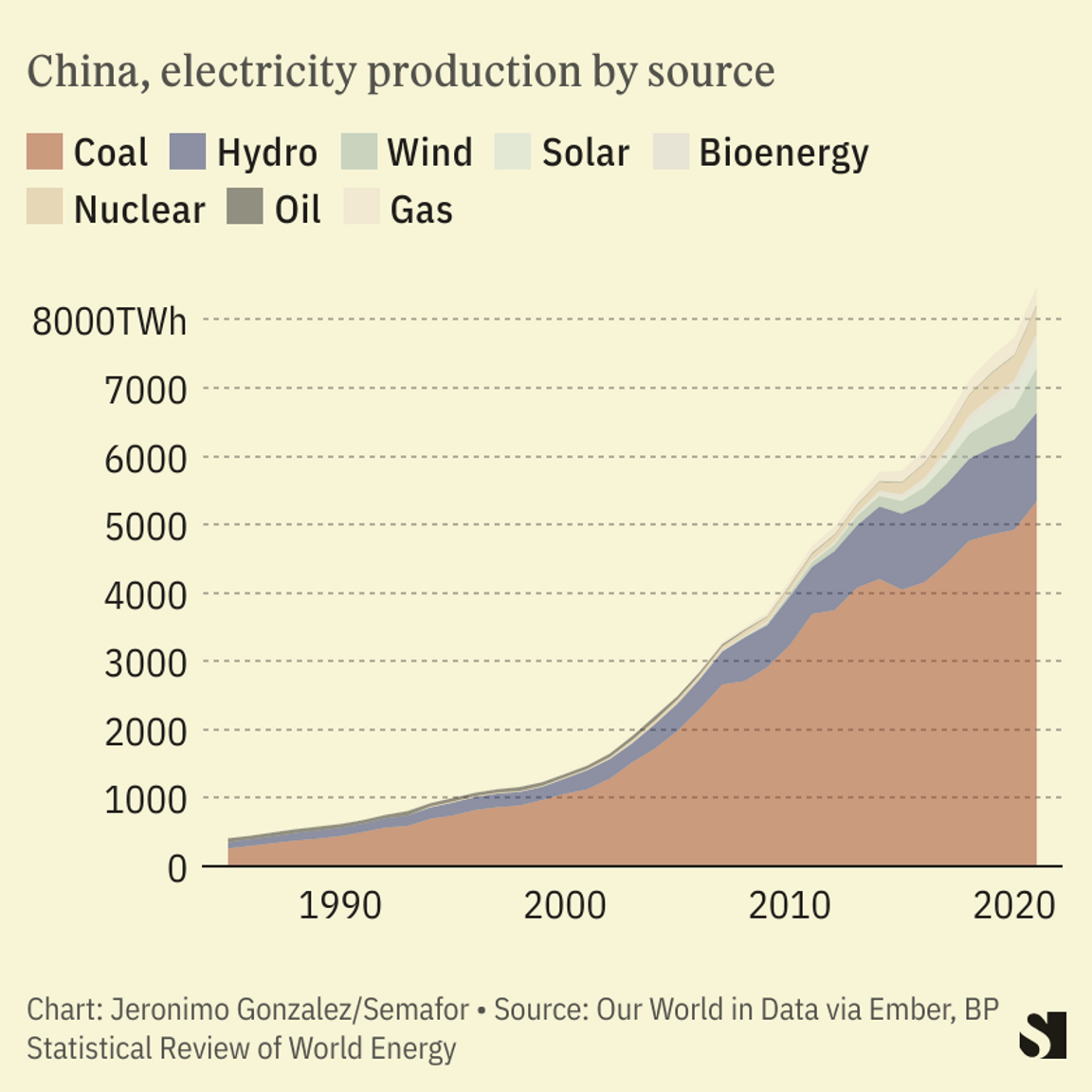

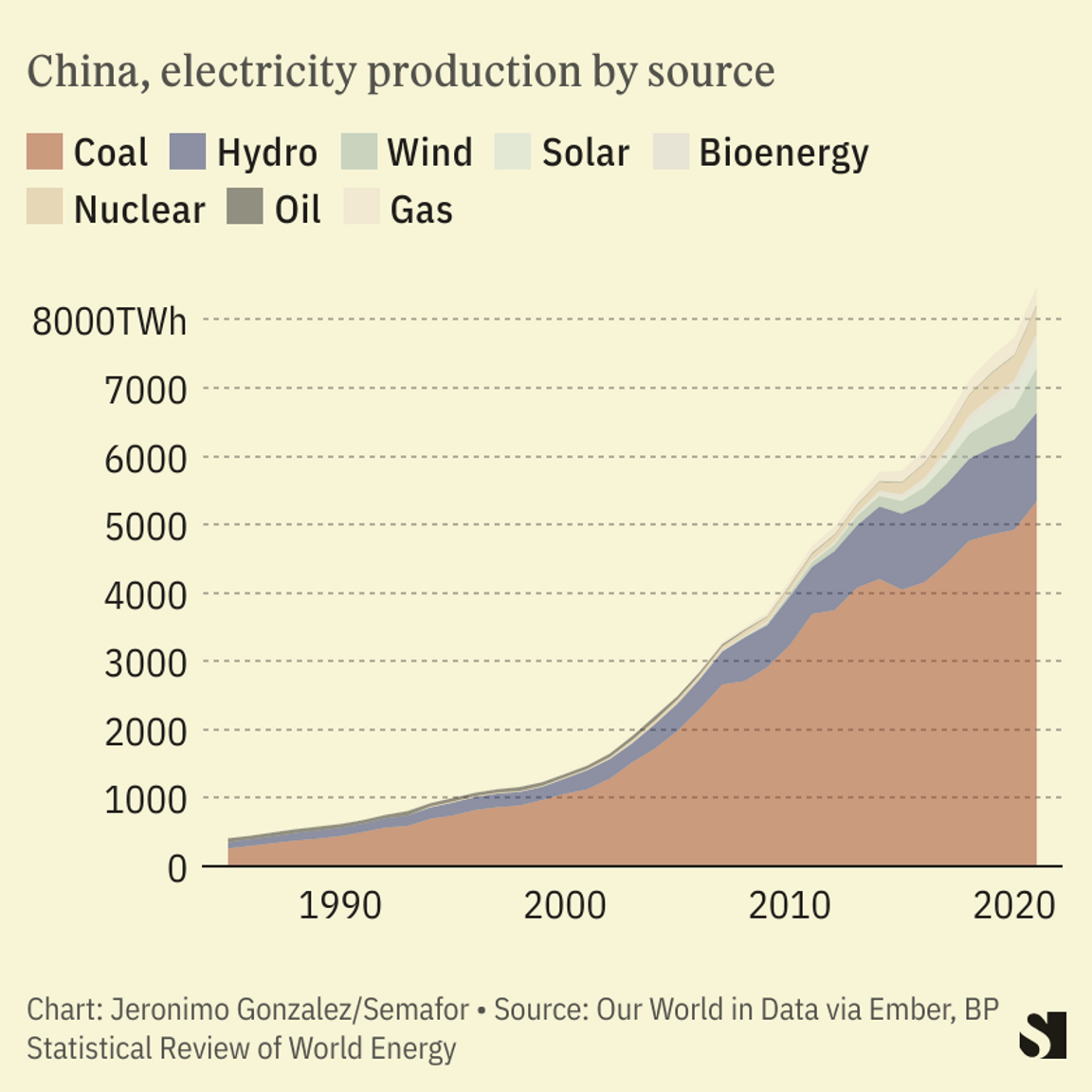

An aerial view of the machinery at the coal terminal of China’s Huanghua port. China Daily/Handout via REUTERS An aerial view of the machinery at the coal terminal of China’s Huanghua port. China Daily/Handout via REUTERSTHE NEWS China permitted more new coal power capacity in 2022 than any year since 2015, and all signs indicate that the surge will continue this year. It OKed 106 gigawatts (GW) of new capacity last year, equivalent to two large coal power plants per week, and a fourfold increase from 2021, according to data published this week. That’s about half of the U.S.’s total coal capacity. Analysts expect the spike to stretch into 2023. At least 60 GW of coal power capacity could be permitted this year, one told me. XIAOYING’S VIEW The coal surge is China’s fight or flight response to two years of domestic power shortages and the energy crisis that resulted from Russia’s invasion of Ukraine. In 2021, widespread power shortages paralyzed factories in manufacturing hubs, such as Guangdong, and left residents facing sudden electricity cuts. As a result, the central government ordered provincial governments to prioritize energy security and boost coal production. Chinese leader Xi Jinping also emphasized that large-scale power cuts “must not happen again” at a key economic meeting at the end of 2021. Then, when power shortages hit Sichuan — a hydropower hub that sends electricity to more economically developed regions — last summer, forcing the local government to cut the power supply to factories for two weeks to keep residential lights on, other provinces, especially those that do not produce their own electricity, realized the importance of being self-sufficient.  The second half of 2022 saw a “steep acceleration” in the amount of coal capacity permitted, as the new data shows. The jump is likely to be a response from provinces, which have the power to sign off new coal plants. Europe’s energy crisis, caused by the invasion of Ukraine, meanwhile made China wary of relying on foreign supplies of energy. So it turned to a resource it has in abundance: coal. KNOW MORE Permitted capacity isn’t the only figure that jumped last year, according to the new data, which was jointly published by Global Energy Monitor (GEM), a U.S.-based non-profit, and the Centre for Research on Energy and Clean Air (CREA), a Finland-based think tank. Last year also saw construction begin on 50 GW of coal power capacity, six times the rest of the world combined, and the most since 2015. Many of these projects had their permits “fast-tracked” and moved to construction within months. Plant retirement also “slowed down further.” China’s latest statistics, meanwhile, show domestic coal production saw a 10.5% year-on-year increase last year, and coal consumption went up 4.3% compared to 2021. The report’s lead author, CREA’s Lauri Myllyvirta, told me he expects 2023 to be “another big year” for permits, barring a backlash from other parts of the central government, such as the financial regulator. Provinces could hand out permits for at least 60 GW of coal power capacity this year to hit a target set by the country’s energy watchdog, he said. Shandong province — which has the largest coal fleet in the country — has announced plans to add six more coal power projects this year, while Jiangsu province has “prepared” 13 coal power units under six projects in January, according to GEM senior researcher Yu Aiqun, the report’s co-author. “These are all likely [to be] permitted in 2023,” Yu said. QUOTABLE The policy signals from the central government seem to have set off a rush of permitting, with provinces scrambling to issue as many permits as possible while the floodgates stay open. |

— Lauri Myllyvirta ROOM FOR DISAGREEMENT China may be ramping up coal power capacity, but some experts I spoke to said that the country would control actual generation from the fossil fuel. Beijing views the expanded capacity more like an insurance policy, to help its inflexible power grid — which cannot easily handle large, unpredictable, inputs of renewable energy — and ensure reliable supply when wind, solar, and hydropower resources are unavailable. After all, the country last year passed a notable milestone, with renewable power capacity surpassing that of coal power, according to Caixin, an independent Chinese financial outlet. Wu Wei, an assistant professor at the China Institute for Studies in Energy Policy at Xiamen University, said coal power plants could operate fewer and fewer hours once renewables become the primary energy source. “Even if [coal power] capacity is increasing, if its operating hours are decreasing, its emissions will decrease accordingly,” he explained. THE VIEW FROM INDIA India is in a similar position to China. It also relies on coal for electricity, and plans to build more coal plants this decade to meet growing energy demands, while concurrently working to increase renewable power capacity. India is preparing to expand its coal power fleet by a quarter — equivalent to nearly 56 GW in capacity — by 2030 unless there is a “substantial drop” in the cost of energy storage, its power minister Raj Kumar Singh told Bloomberg in September. NOTABLE - Instead of focusing on relentlessly expanding coal power capacity, China should devote its attention to improving electricity transmission and distribution nationwide, Shen Xinyi, a researcher at CREA, argues in Sixth Tone, a Shanghai-based outlet.

|