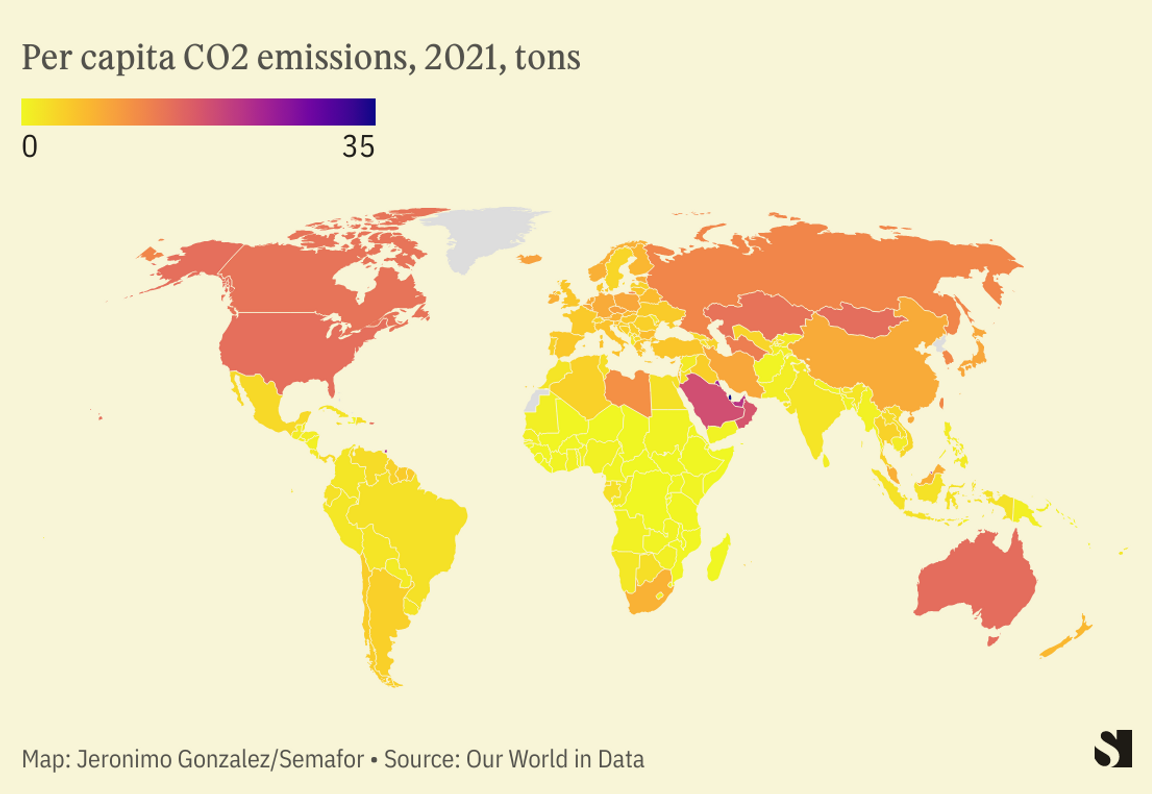

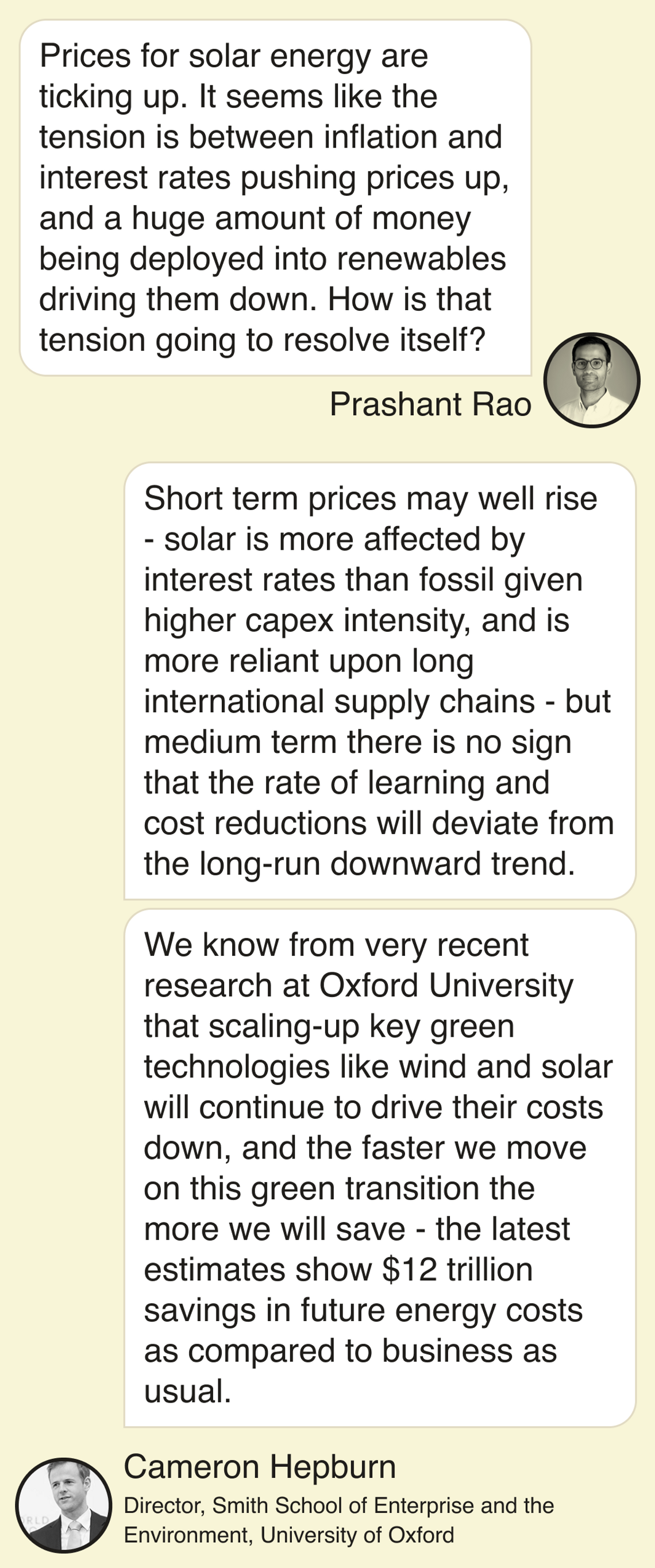

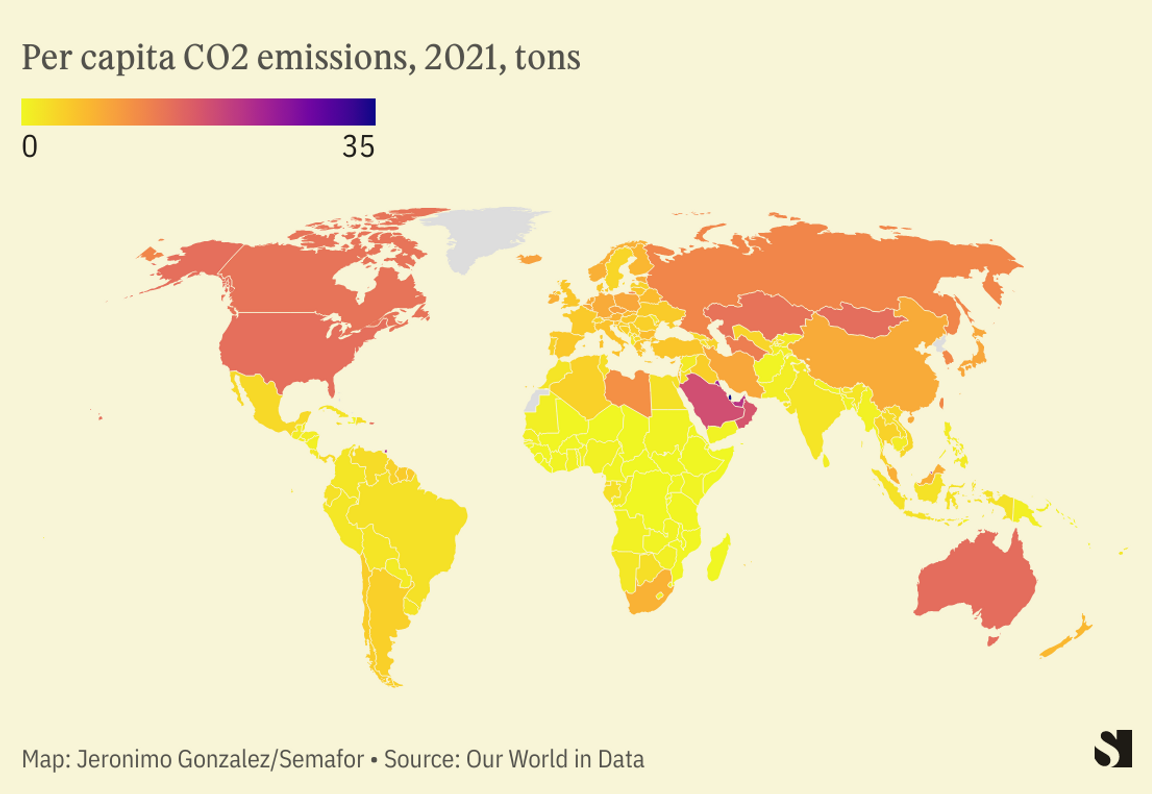

President Joe Biden delivers remarks before signing the Inflation Reduction Act. The White House/Flickr President Joe Biden delivers remarks before signing the Inflation Reduction Act. The White House/FlickrTHE NEWS The Inflation Reduction Act — a landmark law that has turbocharged incentives for clean-energy investments in the United States while enraging America’s closest allies — has experts worried that it places developing countries at risk. These nations are vulnerable to the IRA’s emphasis on reshoring production to the U.S., leaving them comparatively less space in the emerging global supply chain for green technology. The law’s focus on securing domestic supply chains could also drive up prices for green tech globally, making it more expensive for lower-income countries to transition away from fossil fuels, worsening inequality in the process. “The concerns are in the short-term — and by the short term I mean over the next 20 years — that this is really myopic … mercantilism,” said Todd Moss, the executive director of the Energy for Growth Hub, a global network of experts and researchers. “It could be ultimately counterproductive, both for the energy transition and for [the U.S.’s] other global goals.” PRASHANT’S VIEW The IRA is a path-breaking law, helping the U.S. cut carbon emissions by as much as 42% from 2005 levels by 2030. One expert I spoke to argued it would ultimately be seen as the most important piece of legislation anywhere, on any issue, in at least a century, for how much it has solidified American commitment to the energy transition. It has transformed international businesses’ view of the U.S. as a place to invest for the technologies of the future. Yet what its defenders argue were necessary compromises to win domestic political support — such as the Buy America requirements it enforces — have significant costs abroad. And whereas large, rich economies such as the European Union either have the lobbying strength to be heard in Washington, or to muscle together a competing package (the EU has done both), lower- and middle-income countries have few options. Population growth in the coming decades will be concentrated outside of the U.S., as will increases in carbon emissions, and one of the most highly touted achievements at last year’s COP27 summit was a developed-country loss-and-damage fund for vulnerable nations. All of which point towards greater support for, and collaboration with, poorer countries.  The IRA, however, in many ways makes it harder for foreign businesses to access U.S. markets unless they base operations within the country. And its focus on keeping supply chains domestic will, one climate-focused investment banker told me, likely increase costs internationally, at least in the short term, by forgoing more cost-competitive sites worldwide in favor of the U.S., where the price of labor and raw materials can be higher than in developing countries. Ultimately, the risk is that it slows down developing countries’ energy transition by increasing the costs of the technologies they will need to buy, and reducing their opportunities to build businesses along a global supply chain. As Jan Steckel, an expert on climate change mitigation in developing countries at the Mercator Research Institute in Berlin, told me, it also incentivizes poorer countries with much-needed mineral resources to heavily control access to those riches. One example he cited was Indonesia, which is studying the establishment of an OPEC-like cartel for minerals used in the manufacture of batteries. ROOM FOR DISAGREEMENT Even critics I spoke to agreed the IRA was not an unalloyed negative for other countries, rich or poor. In fact, they all acknowledged that it is a far better alternative to the U.S.’s other potential course of action: doing nothing. The only genuine path-not-taken was a “cap and trade” bill that passed the House of Representatives in 2009 but died thanks in large part to a weak economy and industry opposition. Proponents argue such a system would have been less distorting than the IRA’s reliance on subsidies and domestic-production requirements. The U.S. cutting its carbon emissions is also a good thing. Climate change does not respect borders, and so a major polluter spewing out fewer greenhouse gasses helps everyone. The country remains a key hub for global research and development into green technology, and more money dedicated to this effort will eventually lower costs globally — although the operative word here is eventually. QUOTABLE We make no apologies for the fact that American taxpayer dollars ought to go to American investments and American jobs. |

— John Podesta, U.S. President Joe Biden’s senior clean energy adviser, in an interview with the Financial Times. THE VIEW FROM INDIA The Indian official charged with leading the country’s hosting of the G20 this year has sharply criticized the IRA, calling it “the most protectionist act ever drafted in the world.” In an interview with TIME magazine, Amitabh Kant said: “You don’t [decarbonize] by being uncompetitive and doing something which you’ve been against all your life … You believed in market forces and now you do this?” NOTABLE - The IRA as it stands lacks mechanisms to quickly share knowledge with countries whose climate resilience is more clearly tied to their economic development, Rachel Thrasher, an expert in trade and investment treaties at Boston University, noted in a recent piece for Social Europe. It should include funds for developing countries to help them fund climate mitigation efforts, she argued.

|