The News

The U.K.’s biggest private pension fund is planning to use its clout to pressure companies on climate, while firms that backslide on their climate commitments — particularly those in the fossil fuel sector — are likely to face growing shareholder pressure from increasingly impatient investors, a top official said in an interview.

“Things may well get cranked up a bit in terms of engagement,” said Innes McKeand, head of strategic equities at the Universities Superannuation Scheme, which has about $95 billion assets under management. “We’re trying to exert greater pressure to move things in the right direction.”

McKeand argued against selling shares in companies with disappointing climate plans, advocating instead using the USS’s leverage as a major investor to demand improvements. “There was probably a sense of optimism a year or two ago” as big emitters first started committing to climate plans, he told me. But more recently, companies such as Shell and BP downgraded their carbon-cutting targets or said they would invest more in high-polluting existing businesses, which “gives rise to a bit of frustration.”

Prashant’s view

McKeand’s remarks represent a growing belief among long-term investors that heavy polluters must quickly begin to decarbonize not only for the good of the planet, but also if they are to stay in business: “There’s a fiduciary duty that overlays this all as asset owners,” he said. “Doing the right thing in terms of our carbon footprint and making more money, I think those two things are perfectly aligned.”

As evidence of its own impatience, the USS said in the spring that it would vote against individual directors of companies it held stakes in if the firms did not disclose their climate transition plans.

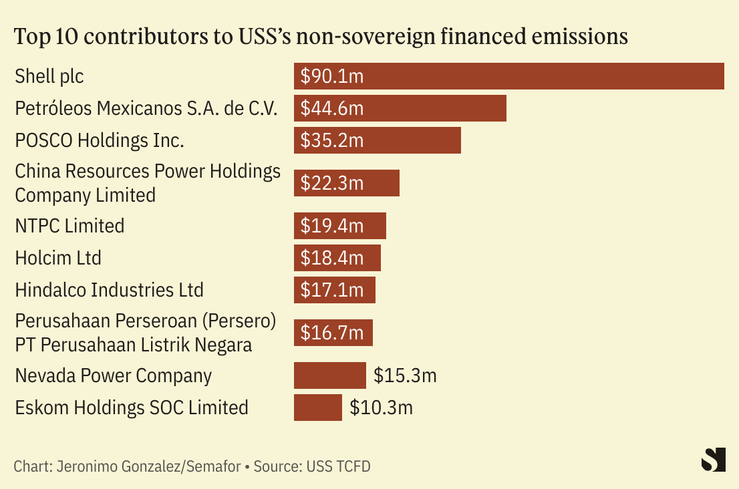

But McKeand’s comments also spotlight an emerging gulf between different types of shareholders, particularly those with stakes in fossil fuel companies. (The USS has stakes in ExxonMobil, Chevron, TotalEnergies, Shell, and BP — the latter two of which are among its top 65 equities ranked by investment.) On one side are assessments such as his, that oil and gas corporate leaders must do more to decarbonize and shift away from their extractive businesses. On the other are investors who view these companies as high-dividend stocks whose profitability is crucial for generating high returns for retirees.

For now, the latter group appear to be winning out when it comes to the oil and gas majors: Shell’s chief executive is reportedly hyper-focused on his company’s share price, and its significant valuation gap compared with U.S. rivals such as Exxon and Chevron. He has — among other things — scaled back his firm’s energy transition plans.

At the same time, climate activists had a dismal run when it came to putting forward shareholder proposals demanding oil and gas companies better report and reduce their carbon emissions — many of which the USS voted in favor of.

McKeand acknowledged recent votes had not been as successful as hoped, but said “signs of backsliding among some companies” suggested to him that investors were likely to become increasingly agitated. “We’re trying to play a long game here.”

Know More

The USS has huge clout in financial markets by virtue of its size, and is increasingly using that advantage to pressure fossil fuel companies to decarbonize. It is also beginning to more deeply integrate climate change-related factors into its overall investment decision-making process, McKeand said. The fund is beginning to more systematically analyze how a carbon tax or other penalty for emissions would affect the valuation of companies it holds stakes in, for example, as well as how other ESG-related factors could influence its investments. “It is [about] trying to take a more holistic view of the assets you’re buying, and take account of what are sometimes some significant risks to the value,” he said.

Room for Disagreement

Alongside the two strands of investors in fossil fuel companies — the USS camp of investors pushing for change, and those who want firms to double down on their strengths and maintain high dividends — is a campaign to disinvest in fossil fuels entirely, arguing that any additional capital put towards oil and gas is money not put towards renewables, ultimately hurting the energy transition. Just last month, the USS fought off a lawsuit from two of its members over its continued investment in coal, oil, and gas.

Quotable

“Investors could pick the highest emitting asset they own and sell it and reap an enormous carbon dividend. But is that doing the right thing? We’re not convinced it is. How do we change the real-world emissions? That sometimes means holding on to assets which look poor from a carbon emissions perspective right now.”

— Innes McKeand

The View From South Korea

Pension funds the world over are under pressure to disclose their climate-related risks and investments, with South Korea’s mammoth national pension service — which manages assets worth about $750 billion — facing a lawsuit from climate groups last month calling for it to publish the details of recent discussions over whether it should divest from coal.

Notable

- Some climate-conscious pensions are also losing patience with the asset managers who help guide their investments and voting decisions. Earlier this year, Brad Lander, who oversees New York City’s public pensions, said he would consider firing BlackRock if the firm doesn’t improve its climate record — and lashed out again after BlackRock appointed a Saudi oil executive to its board.