The News

The trade deal agreed this weekend between the US and the European Union hinges on natural gas — but both sides seem to have overpromised what each can realistically buy and sell.

In exchange for a modest reduction in economy-wide tariffs imposed by the US, and exemptions for aviation and some other sectors, EU officials agreed on Sunday to invest $600 billion in the US and to buy $750 billion in American energy products over the next three years. The investment promise is already crumbling, as the bloc has admitted it has no control over how the private sector spends its money.

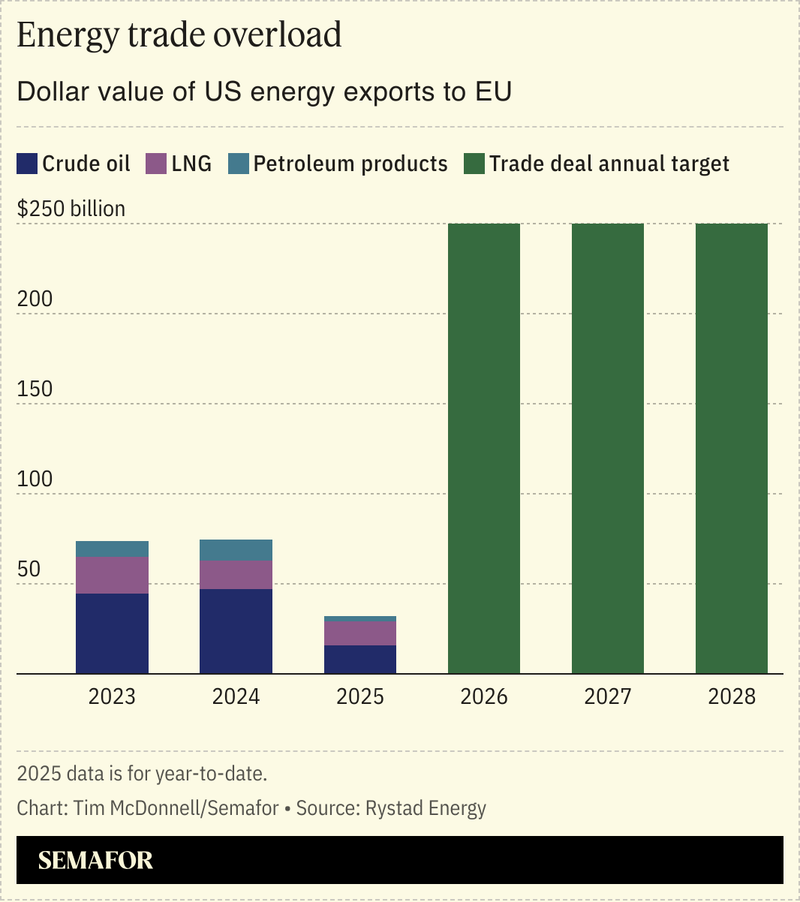

The energy promise will be next to fall. It faces the same fundamental problem: Bureaucrats in Brussels and Washington can’t dictate the flow of global energy trade. And even if they could, the new target is far out of reach. Total US energy exports to the world were worth $318 billion last year, of which about $74.4 billion went to the EU, according to Rystad Energy. So to meet the target, the EU would need to more than triple its purchases of US fossil fuels — and the US would need to stop selling them to almost anyone else.

“These numbers make no sense,” said Anne-Sophie Corbeau, a researcher specializing in European gas markets at Columbia University’s Center on Global Energy Policy.

In this article:

Tim’s view

Starting in his first term, Trump keyed in on liquefied natural gas as a central pillar of his trade strategy: The world wants more of it, the US has a lot of it, and the quickest route to winning Trump’s heart on trade is to promise to buy plenty of it.

China did this in 2019, followed in Trump’s second term by Japan, South Africa, and others. But the US gas supply — while indeed vast — isn’t infinite, and following the new EU deal there are officially far too many people in the queue for it.

The problem with Trump’s strategy, apart from its physical impossibility, is that it weakens his hand in future trade negotiations. It’s now less clear what Trump expects other countries to offer him in exchange for favorable tariff terms. To the extent the White House is able to push gas to one place or another, any further deals predicated on promises to buy US energy will unavoidably mean shortchanging those allies who already signed up, and potentially leave investors holding the bag on multi-billion-dollar import facilities that go underused. And the more US gas Trump gives up for sale abroad, the less will be left behind for sale at home, undermining his promise to keep consumer energy prices low as the data center boom drives US utilities on a mad rush for more gas (especially as the administration is simultaneously pushing to cut support for renewables).

“World leaders have clearly learned that they can kind of cajole [Trump] into positive press by offering these big numbers [on energy sales],” said Alex Jacquez, a former senior Biden administration official on the White House National Economic Council. “Whether any of that is enforceable, whether it’s going to happen, whether it’s actually good for the broader US energy dominance strategy, is all really doubtful.”

Trump is also establishing a pattern whereby countries can make what is essentially an empty promise on energy, extract better trade terms for the time being, and then hope that Trump leaves office before he catches on. That, again, is what China did back in 2019; its energy imports from the US never came close to what was promised at the time, and in the meantime it bought itself a few more years of relative detente in its trade tensions with the US.

It’s not clear where all this additional gas could come from, or where it will go: US LNG export facilities are already at capacity. More are in the works and could be operational in the next few years, but during that time, Europe’s gas demand is expected to level off. This is to say nothing of the fact that the European Commission — the bloc’s executive arm, which negotiated the deal — does not have the power to direct individual member states to purchase more LNG, or any other commodity. Officials in Brussels have privately suggested that even if LNG imports don’t pick up, per se, Trump may want to see concrete interim steps like new investments in import terminals. But Europe’s existing regasification capacity already exceeds its total gas demand, Corbeau said. Even as the EU pushes to completely sever its energy ties with Russia, there is practically no headroom for new gas import infrastructure.

And even if there was, it’s not clear that a drastic boost in Europe’s energy reliance on the US is in the bloc’s long-term strategic interest. Russia’s invasion of Ukraine revealed the risks of an overreliance on a single, politically unstable supplier, said Laurie van der Burg, global public finance manager at the advocacy group Oil Change International: “The EU has just fallen into another dangerous fossil fuel dependency trap.”

Room for Disagreement

Wall Street was more bullish about the possibilities for greater US-Europe energy trade: Share prices of top LNG companies jumped following the deal. And Venture Global, a leading builder of US LNG export terminals, closed a $15 billion financing round that it said involved 30 international banks.

Notable

- Germany plans to cut energy costs for consumers and businesses by drawing nearly $50 billion out of its federal energy transition fund.