The News

Western countries should head off the creation of new OPEC-like producer cartels for critical resources such as lithium by inviting mineral-rich nations to join an existing rich-country club, the head of a major mining trade association told Semafor.

Bringing Latin American and African countries into the Minerals Security Partnership (MSP) would also promote mineral recyclability by allowing producers and consumers to balance their concerns and economic priorities, the Chief Executive of the International Council on Mining and Metals Rohitesh Dhawan said.

The MSP “has been too late to invite the emerging world into it,” Dhawan told me. “That I think is a huge mistake because the narrative that it feeds for countries in Africa, in particular, is, ‘Here the West goes again, coming to our countries, taking our mineral riches, not allowing us to develop’.”

Prashant’s view

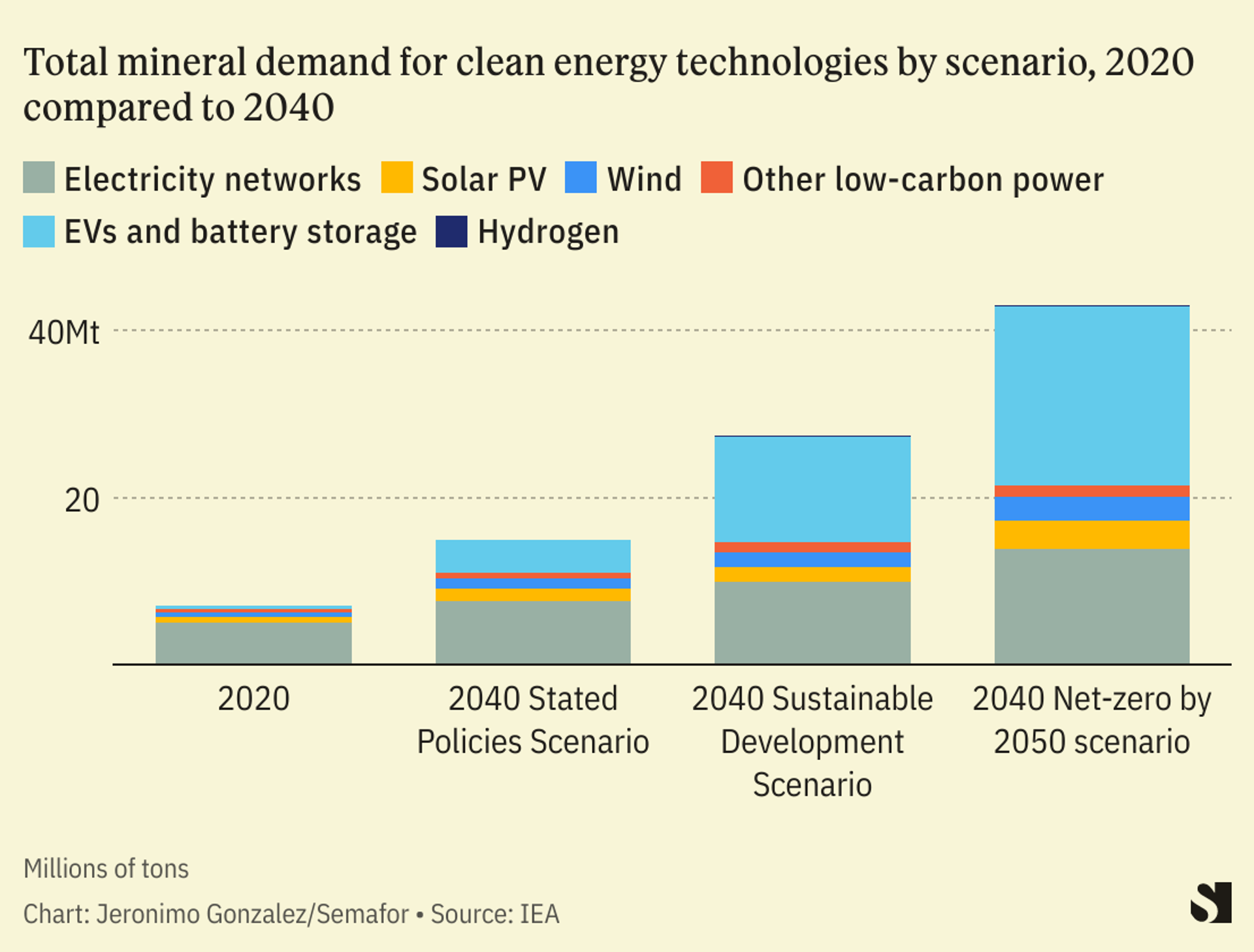

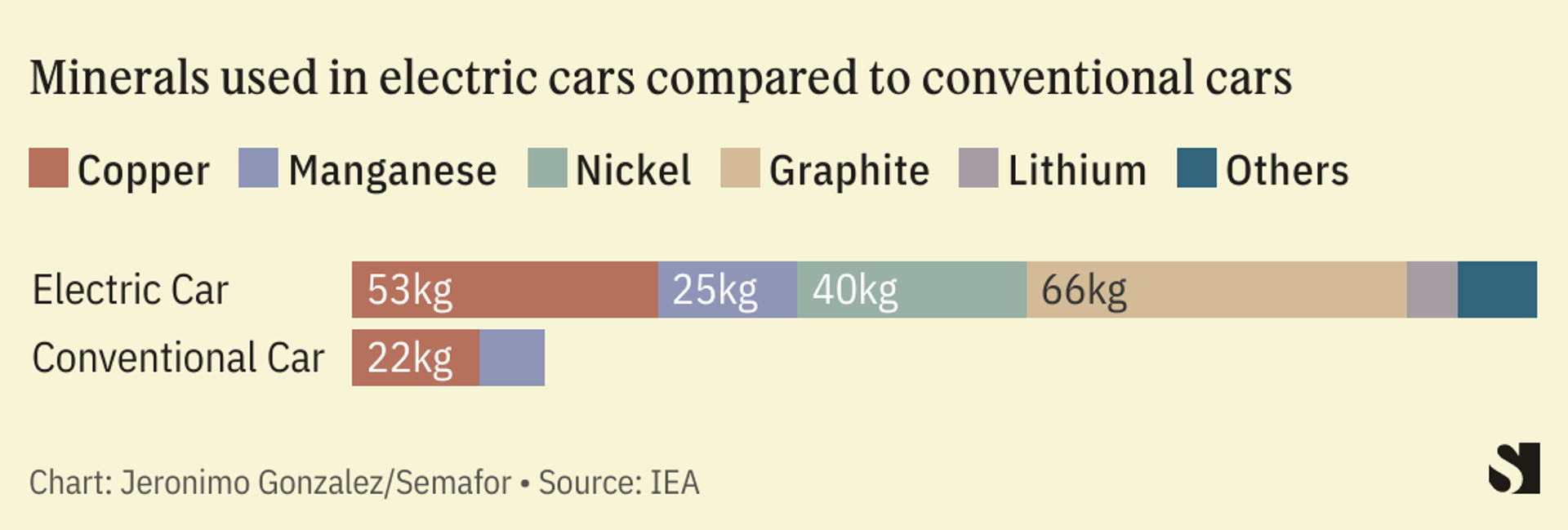

The thinking behind mineral-rich countries seeking to join together is understandable: The world must electrify its economy and wean itself off fossil fuels as part of the energy transition, and minerals are crucial for this process, underpinning the construction of wind turbines, batteries for electric cars, and all manner of other crucial goods. Countries abundant in them want to take advantage and garner as much wealth as possible from their natural resources.

And indeed, countries around the world — in Latin America’s “lithium triangle” where that metal is abundant, Indonesia, which is rich in nickel, and elsewhere — have suggested forming producer groupings in the model of OPEC to control supply and thus have greater sway over the international prices of their raw materials.

Yet the broader downsides — at least to the rest of the world — of such an approach are huge. OPEC enjoys considerable influence over oil markets, but its members are routinely criticized for claiming to be balancing supply and demand while in fact prioritizing their own domestic budgets and exacting a significant cost from the global economy.

Dhawan’s suggestion — while being beneficial to his organization’s member companies by undercutting such power — has a lot going for it. The MSP already includes both major producers such as Australia and Canada, as well as consumers, but is mostly made up of rich Western countries. India was inducted into the group last month, and an array of African countries — Angola, Botswana, the Democratic Republic of Congo, South Africa, Tanzania, Uganda, and Zambia — attended an MSP meeting in New York City in February, though none are full members.

In his telling, clubbing both groups together would also help promote mineral recyclability. Unlike fossil fuels, minerals and metals can be reused and recycled, which offers both long-term potential for their sustainability, as well as long-term fears that consumer countries could build up stockpiles and then cut producers off. That latter scenario, he worried, would leave mineral-rich developing countries thinking, “After telling us that we can’t exploit our coal reserves … now you’re not even gonna buy our battery metals because you found a way to circulate these in your economy.”

Know More

Avoiding the creation of an OPEC-like grouping isn’t the only lesson the mining sector should take away oil and gas, Dhawan said. The industry should also improve transparency, acknowledge its role in climate change, and admit it isn’t trusted by the public.

“For too long — including today, frankly — the oil and gas industry has been saying to people, ‘Well we produce the stuff, we don’t burn it, you burn it, so it’s your problem, not ours’,” he told me. “We believe in the signs you get in the shops that say, ‘If you break it, you own it’. If we have played a role in breaking something, like our climate, then we own the problem together with everybody else.”

Both industries have long been targets of criticism from environmental and Indigenous rights groups for their purported carelessness in dealing with communities and wildlife in their pursuit of natural resources. Mining has lessons to learn from oil and gas’s successes, too, Dhawan acknowledged: Despite high-profile disasters such as the Deepwater Horizon explosion, oil and gas companies were consistently better at health and safety than mining businesses, he said. There are more examples of countries becoming wealthy off the back of oil and gas exploration than from mining, Dhawan pointed out, even if that wealth is ultimately poorly distributed.

Indeed, some analysts have suggested that, rather than gearing up for a shift towards renewables — which deliver lower, albeit consistent, returns when compared to boom-and-bust fossil fuels — oil and gas majors should instead pivot towards mining, an industry that in some ways better mirrors the financial returns fossil-fuel shareholders expect, and which leverages oil and gas companies’ historic expertise in advanced sciences such as geology.

Quotable

“The industry’s traditional approach has been … when faced with criticism, to respond with all the great things we do, and to say, ‘Yes, but we create jobs, and economic value, and supply chains and all these other things, and don’t you like your iPhone, and don’t you like your airplane that you’re flying on’,” Dhawan said. “That’s been our mistake for the last two, three, four decades, that we have not accepted and admitted that we have acted in ways that make it hard for people to trust us.”

The View From Indonesia

Indonesia offers a case study for many of the challenges facing the minerals sector. Its vast island network is home to the world’s biggest supply of nickel, but the metal lies below thick forest. In 2020, Jakarta banned the export of nickel ore, and intends to bar the overseas sale of an array of other minerals to boost the development of local refining capacity. Last year the Indonesian government said it was studying establishing an OPEC-like grouping for metals needed to make batteries. Experts are increasingly looking to the country’s decision as a model for how developing countries and mineral-rich nations will handle the energy transition.

Room for Disagreement

Even if countries like Indonesia wanted to form an OPEC-like cartel, they would face significant challenges. When it comes to nickel, for example, MSP members Canada and Australia are major players. Indonesia is also heavily reliant on Brazilian and Chinese companies to help it extract the metal, unlike, say, Saudi Arabia, which has a state-owned company dominating its domestic oil industry. Analysts also caution that such moves could drive away investment, particularly among businesses able to help build up refining capacity in mineral-rich nations which would help them capture more of the economic value of their resources.

And the MSP itself is no silver bullet, particularly if richer consumer countries do not partner with mineral-rich ones to help them develop the processing and manufacturing capacity that helps them build a value chain, Todd Moss, the executive director of the Energy for Growth Hub, a global network of experts and researchers, told me.

Notable

- Metals and minerals aren’t just key to batteries. They’re necessary for semiconductors, too, and China’s recent decision to ban the export of key metals in chipmaking has forced countries and companies to look at shifting their supply chains, The Wall Street Journal reported.