The News

African countries — beset by high levels of debt and vulnerable to fast-rising global interest rates — are increasingly turning to green financing solutions.

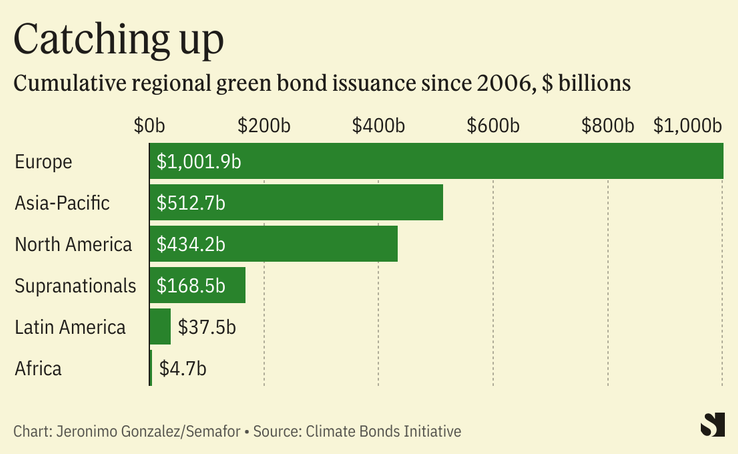

Egypt and Angola — two of the continent’s largest economies, which both struggle to access international bond markets at competitive rates — are preparing ESG-linked debt issuances in the coming months. More countries could join them. International lenders including the World Bank, European Investment Bank, and African Development Bank are promoting the tool, even promising to guarantee billions of dollars of such debt to encourage private investors to fund African countries’ Sustainable Development Goals. But so far only four nations have issued green bonds in Africa, representing less than 1% of the global green bond market.

“The market … is effectively closed to all but a couple of entities in Africa,” Matthew Vodola, founder of Windham Advisory, a U.S. firm specializing in climate finance in emerging markets, told me. “A climate angle makes it possible to find support from multilateral backers and is the most viable way to catalyze private or commercial capital.”

Lara’s view

Green financing — if properly managed — could solve several problems at once for African countries.

For one, it could give them access to lower-interest bonds than they can currently obtain. Some 25 African countries are classified as at high risk of debt distress, and many are overleveraged, with high borrowing levels exacerbated during the worst of the COVID-19 pandemic. Green bonds come with lower interest rates because in many cases multilateral development banks back them: The AfDB, for example, has pledged to guarantee billions of dollars of green-financing issuances to encourage private investors to participate in Africa’s nascent green bond market.

It is also a useful tool to attract international investors who are increasingly shying away from developing and emerging economies, parking their money in what are seen as safer assets as Western central banks ratchet up interest rates.

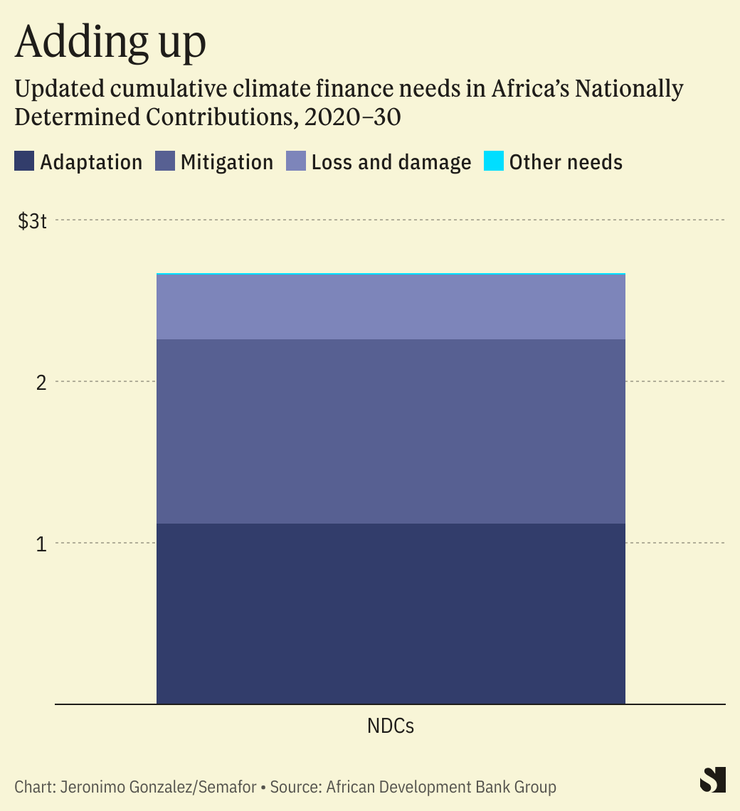

And it provides much-needed financial support for countries aiming to tackle climate-related challenges: Patrick Verkooijen, Chief Executive of the Netherlands-based Global Center on Adaptation, an international organization focused on climate adaptation, told me that emerging markets have had to rely heavily on capital markets as rich nations have fallen short on promises to provide climate financing to the developing world.

Know More

The main difference between green bonds and their traditional counterparts is that borrowers ostensibly direct proceeds to projects with environmental benefits. But while countries can advertise how they intend to use the income, there is not usually a clear way to force them to carry out the promised sustainable projects.

Egypt is issuing Africa’s first renminbi-denominated green bond this year, partially guaranteed by the AfDB, and though the issuance’s interest rate has not yet been set, a prior Egyptian green bond in September 2020 — North Africa’s first — paid interest of 5.75%, compared to debt Cairo issued this year at 10.85%. The stakes for Egypt are significant: It spends 45% of its annual budget on debt-servicing costs.

Room for Disagreement

As countries with weak credit ratings, unsustainable debt-to-GDP levels, and zero track record of delivering on climate projects begin accessing the green bond market, questions are being raised over the “sustainability” of sustainable financing.

Angola’s own finance minister registered his wariness about his government’s plans to issue an ESG bond of up to $1 billion next year, because of broader concerns over the need to stabilize its debt. The oil-rich country has struggled to navigate its debt burden in recent years and completed a restructuring in 2020. According to research from Allianz, debt service will increase from 2023 onwards and Angola will dedicate an average of 80% of annual fiscal revenues in 2023-2025 to debt repayment. Its planned green bond would add even more stress to the balance sheets.

The View From Europe

Europe is home to the world’s most developed green-bond market, comprising almost half of global issuance. The EU also unveiled a common framework for green bonds this year aimed at providing a high bar for issuers to meet in terms of transparency and reporting. EU green sovereign bonds are subject to higher scrutiny than in other markets and have rock-bottom yields: The bloc has a mammoth €12 billion 15-year green bond priced at 0.453%.

Notable

- Investments in green bonds aren’t solely reliant on multilateral development bank backing, or a belief that such issuances will help the energy transition, according to experts at a King’s College London panel. Just as important are expectations that demand for green bonds is likely to outstrip supply for a long time, particularly as increasing numbers of pension funds strive to meet ESG criteria.

- Within Africa, the extent of the climate-financing shortfall varies wildly: The so-called climate-investment gap is 3% of GDP in North Africa, but 26% of GDP in central Africa, research from the Climate Policy Initiative, a think tank, showed.