The Scoop

Google is closing in on deals to expand a new method for buying clean electricity that could open a major new path to viability for low-carbon power projects that have been too expensive for utilities to pursue on their own.

Google revealed last week that it had signed a first-of-its-kind deal involving the Nevada utility NV Energy and the geothermal power startup Fervo. The Nevada deal is an untested iteration on the traditional power purchase agreement (PPA), a type of clean power contract that Google also pioneered nearly a decade ago. Under the contract (the value of which wasn’t disclosed), Google will pay a higher rate for power at its Nevada data centers and other facilities. In exchange, NV Energy will commit to a long-term deal to buy 115 megawatts of newly-built geothermal power from Fervo.

Now, Google is working on deals following the same approach with utilities including AEP, Dominion, Southern Company, and the Tennessee Valley Authority, Caroline Gollin, Google’s global head of energy market development and innovation, told Semafor. Those deals will go beyond geothermal, and could include advanced nuclear power plants, long-duration storage, and grid enhancements.

Tim’s view

PPAs have arguably been the most powerful tool for bringing clean energy into the grid in the US and Europe — but they are in need of a serious makeover if that impact is to continue. A new approach to PPAs is especially urgent to ensure the wave of new power demand from data centers and EVs isn’t met with fossil fuels.

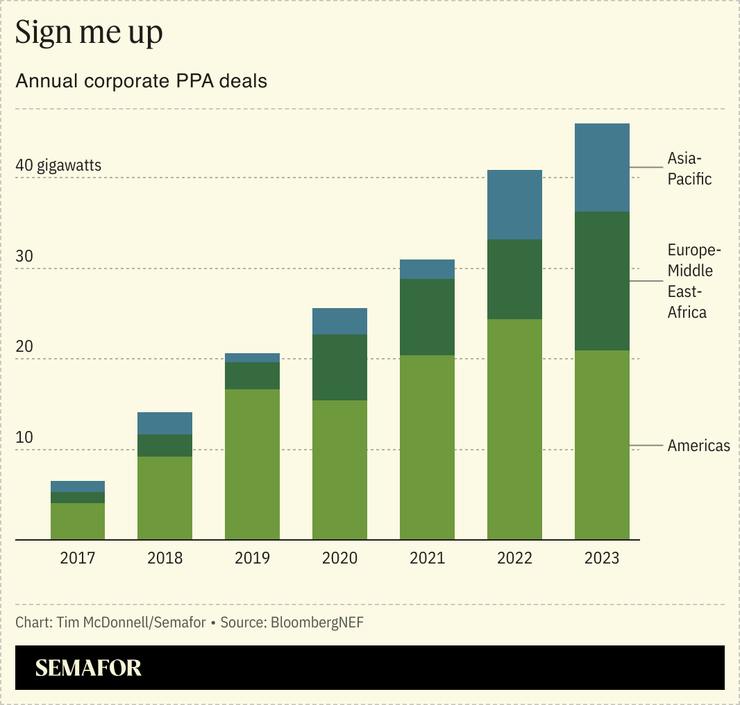

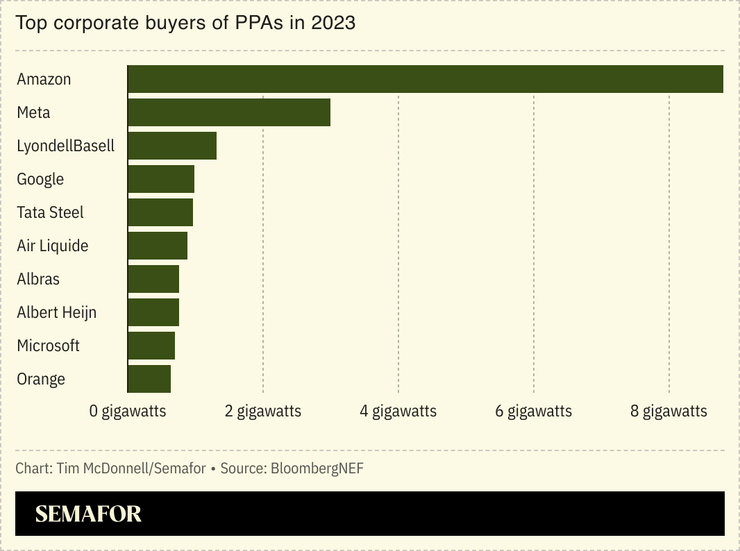

In a typical corporate PPA, a company signs a 15-20 year purchase agreement with a solar or wind farm developer. In most cases, the buyer isn’t actually taking power directly from the plant, but is technically buying only a certificate representing the power’s zero-carbon attributes; the power itself flows into the local grid and can’t be counted against anyone else’s carbon footprint. These deals make new projects bankable that otherwise wouldn’t be, and they’re one of the only ways for a company to jump ahead of whatever its utility is willing or able to do to decarbonize. They are also typically structured so that if the prevailing daily price of power falls below the fixed rate in the PPA, the buying company will get paid back the difference, which for Google and other buyers has become an important side stream of revenue. In 2023, companies globally, mostly in Big Tech, signed a record 46 gigawatts of PPAs, according to BloombergNEF, equivalent to the overall power output of 100 midsize coal plants.

But traditional PPAs are running into a few “serious limitations,” Gollin said. They aren’t available in the half of US states with vertically integrated utilities, where deals that exclude the utility aren’t allowed. It can be a headache, Gollin said, to manage essentially two separate sets of energy bills, from the PPA certificates and the actual power the company is still using from the utility. They often aren’t economic for large, expensive, cutting-edge baseload power projects like geothermal and advanced nuclear. Wind and solar PPA prices are rising in the US because of high inflation rates and supply chain bottlenecks, forcing many developers to renegotiate. And the explosion of PPAs has essentially created a parallel virtual grid, Gollin said, which is a headache for utilities that remain responsible for transmitting power they weren’t involved in planning.

“We don’t want to build an island just for Google, because that’s not going to catalyze the type of change we want to see,” Gollin said.

Google’s “clean transition rate” solves these problems by essentially re-introducing the utility as a middleman. The utility decides what specific mix of climate tech is best, and negotiates a rate large buyers can pay to tap it. Being able to access a lot of advanced clean baseload power will lower by 40% the cost for Google to meet its goal to source 100% of its power from clean sources around the clock by 2030, compared to relying exclusively on intermittent wind and solar, and conventional batteries. And it can push Nevada’s overall grid to be cleaner without raising rates for regular customers. Every gigawatt of clean baseload the utility builds is one less gigawatt of gas generation it would need to build to ensure reliability as demand increases.

The latter, Gollin said, results in “a bunch of stranded assets on the system, and it’s a poor use of money.”

Know More

The other problem with PPAs is that their long terms, and uncertainty about how the future market power price will compare to the PPA rate, make them impossible for many smaller companies to commit to. Watershed, a sustainability accounting startup that helps companies find clean power, last week launched a new product that’s essentially a group PPA, in which demand from a number of buyers is pooled together — the first batch includes DoorDash and the video game design platform Unity, and will support the construction of nearly 100 megawatts of new solar farms in Michigan. The deals are shorter, and buyers have no obligation to pay more if the market power price increases.

“Sustainability teams are often blocked by the fact that they are viewed as a cost center,” said Matt Konieczny, Watershed’s head of clean power. “What we’ve unlocked here is the ability to deliver on your targets at a fixed, predictable cost.”

The View From Nairobi

PPAs are also critical for bringing more clean energy online in developing countries and pushing out fossil fuels. Kirtika Challa, global head of power at the Nairobi-based renewables investment firm CrossBoundary, said the company has a growing business standing up PPAs for malls, breweries, and other large industrial or commercial customers around the African continent. But the real prize would be to sign more PPAs with the state-owned utilities that control the grid in most African countries. The trouble is, those utilities are chronically cash-strapped, with poor credit scores, and even with a government guarantee on the deal they can’t get banks to trust a PPA enough to put cash up front. One solution, similar to Watershed’s approach, is to have a regional power trader orchestrate group PPAs spread across multiple utilities; that solution has been working well across the southern African grid, Challa said.

Another obstacle to PPAs in developing countries is that the deals are typically dollar-denominated, a problem for governments with low foreign currency reserves. One solution proposed by the African Development Bank is for governments to essentially use their vast reserves of critical minerals as collateral, promising a lender a cut of future mining profits if PPA payments fall through.

Room for Disagreement

Europe is taking over from the US as the top destination for traditional PPAs, which aren’t going to disappear anytime soon, said Aleksandra Klassen, who manages European PPAs for the sustainability consulting firm Schneider Electric. Regulatory and carbon price pressure in the EU are driving higher demand for PPAs, but deal prices are generally falling as developers compete against each other, and against the falling cost of natural gas, for financing.