The News

What once shocked markets is now becoming routine: for the third straight month, OPEC+, led by Saudi Arabia, agreed to raise output, potentially lowering prices. It’s the opposite of what cartels are supposed to do.

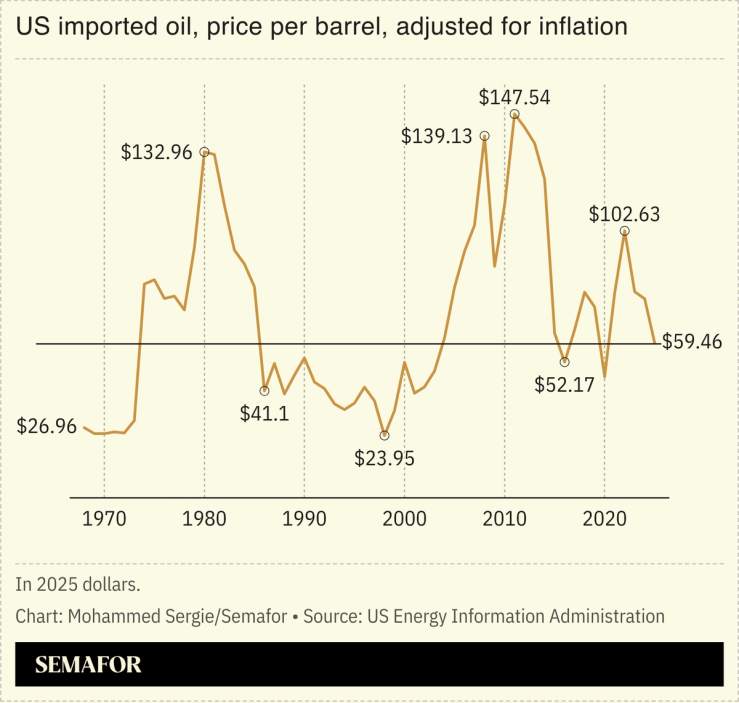

Goldman Sachs forecasts oil averaging $60 a barrel this year and dipping to $56 in 2026. Eurasia Group puts the range between $45 and $75 a barrel through 2027 — a steep drop from the $88 average between 2022 and 2024. The consultancy sees the global economy entering a “low-cost energy cycle.”

Know More

That’s a win for consumers, and may work out in the long term for Gulf producers whose low-cost barrels will outlast the competition. In the short-term, however, there are jitters.

Bahrain, Kuwait, and Saudi Arabia are all expected to post deeper deficits this year, and debt issuance for the latter two is rising. The other three Gulf countries are still in surplus territory, according to the International Monetary Fund, but lower oil revenue could slow spending and drag on foreign investments: both are crucial for creating new revenue streams to diversify the economy. Saudi Arabia’s non-oil private sector expansion slowed in April, according to investment bank Riyad Bank.

Saudi officials are relatively sanguine. Finance Minister Mohammed al-Jadaan told the Financial Times last week that the government will stick to its spending plans but take a look at which projects to prioritize, making sure to “spend in support of the growth.” With deficits expected to rise to as much as 5% of GDP, he said the kingdom’s low overall debt means it has a long runway before it reaches its self-imposed debt-to-GDP ceiling of 40%.

Saudi stocks were the world’s worst performers in May, Bloomberg reported. Inflation-adjusted oil is on track to record its third-lowest annual average in 22 years — eroding exporters’ purchasing power. At these levels, tensions within OPEC+ are mounting.

Analysts are still debating the OPEC+ decision. Some say it’s to punish OPEC+ members cheating on quotas, others point to the need to reclaim market share from US shale producers, or to appease US President Donald Trump’s call for lower prices. Most likely, it’s all of the above. The result is the same: oil revenue is sliding and eventually, someone will pay the price.