The Scene

Rep. Jasmine Crockett, D-Texas, kept herself busy on Tuesday. She confronted Elon Musk in a closed-door meeting, got Supreme Court justices John Roberts and Clarence Thomas arrested, ended the career of Georgia Rep. Marjorie Taylor Greene, and humiliated Colorado Rep. Lauren Boebert.

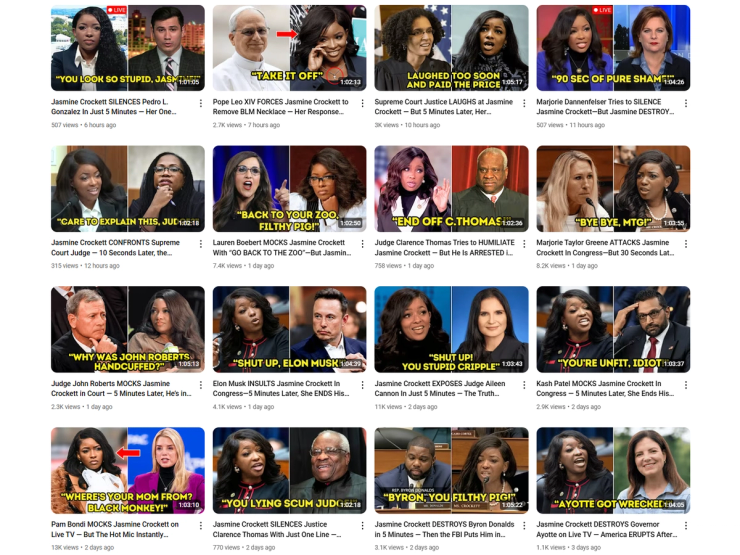

Crockett’s busy — and fictional — day unfolded on “Mr. Noah’s Stories,” a YouTube channel that inserts the names of public figures into lengthy fanfiction videos. It’s one of many accounts, across social media sites, that serves the appetite for dramatic, partisan stories by making them up.

With little fanfare — maybe “with jaw clenched,” as these overwritten stories often put it — Crockett’s gotten a few of the fakes taken down, and ignored the rest.

“Clearly the algorithm loves my name, so people do stuff with my name,” Crockett told Semafor. “I’ve just told people at this point, if it’s an AI-generated voice, it’s probably a lie.”

Hard to avoid on TikTok, YouTube or Facebook, AI-generated slop has become a barometer of political fame, just as it has of pop culture celebrity. Cabinet secretaries, members of Congress, and presidential family members regularly appear in fake stories with tidy narratives.

They fly under the radar. They sometimes get more views than real-world political reporting that’s not built for the algorithms.

And they’ve become irritating, and worrying, to some members of Congress. New York Rep. Yvette Clarke, who has introduced legislation to regulate and ban AI “deepfakes,” told Semafor that the need for reform was growing.

“We’re definitely going to reintroduce it because the technology is becoming even more expansive, and with AI that supercharges it,” Clarke said. “The ways in which our communities are victimized, particularly Black women, by deepfake technology is unacceptable.”

In this article:

Know More

The proliferation of fake AI stories about politicians haven’t created real political problems for them yet. Other online fakery, like bogus estimates of politicians’ net worth, has taken up more of their time — lies to debunk before voters start to believe them.

These fake stories are very different, and tend to make their subjects look good. Pete Hegseth Rolls Up His Sleeves to Cook for Disabled Veterans, an illustrated story that has been reposted across Facebook’s bogus news pages, suggests that the media is unfairly ignoring Hegseth’s decency and charity. The most popular version of this, including an AI image that shows the defense secretary’s finger stuck inside of a levitating hamburger, has been shared nearly 6,000 times.

President Donald Trump and his family were some of the first subjects of this phony content mill, with less discouragement than Crockett. During last year’s presidential campaign, the Trump operation shared AI images of the candidate saving pets — cats, dogs, and even some squirrels — from swarthy immigrants and raging hurricanes.

In this new term, the White House has shared He-Man Trump images created with AI; most controversially, the president shared a computer-generated fantasy of Gaza, after a possible Trump takeover, on his Truth Social account.

AI accounts have added to this with illustrated stories about the presidential family humiliating Trump’s enemies — “Do you know that Baron Trump has engaged in a public confrontation with the professors who signed the letter against Trump?” — or singing gospel music. (The latter is one of the many pseudo-Trump music videos from Vivo Tunes, which has more than 230,000 YouTube subscribers, and a disclaimer that its content does “not reflect the thoughts or attitudes of the imitated artists.“)

The newer, more politically diverse fakery is typically about conflict, not singing contests. It’s packaged like breaking news, reported from an alternate reality where clapbacks and call-outs can instantly send people to prison. It mangles some details, but gets others right; a confrontation between Attorney Gen. Pam Bondi and a non-existent liberal senator unfolds in Dirksen 226, which is indeed where the Senate Judiciary Committee holds its hearings.

Since Jan. 27, when the account was created on YouTube, Mr. Noah’s Stories has added more than 42,000 subscribers and clocked more than 5.6 million views. The Crockett character was introduced on March 31, when she confronted a judge with evidence of his corruption, “walking into a storm she always knew was rigged against her.” It was a rewrite of a story that had initially starred Michelle Obama. But it was a much bigger hit.

David and Kadia’s View

Most of the political debate about AI and deepfakes has focused on potential reputational damage — words being put into a politician’s mouth, a candidate being placed at an event they never attended. After New Jersey Rep. LaMonica McIver gave an interview about her arrest at an ICE facility, her lips were altered to match the singing voice of a Democratic activist. That’s the sort of thing Clarke’s legislation could prevent.

The AI fanfiction is another story, taking advantage of the freedom major social networks give to AI creators and churning out hours of strange fake news. And to be famous, in 2025, is to be faked. Crockett’s emergence as an AI slop star is a function of her political stardom. Her real-life “clapbacks,” which inspired a clothing collection run by her reelection campaign, are popular enough for the slop merchants to create dramatic imitations.

Unsurprisingly, no creator of this content wanted to talk about it. (The accounts that made it possible to reach out for comment didn’t reply to any questions.) They have found an audience, however small and however bot-laden, that’s so hungry for political conflict stories that it’ll click on fakes.

Notable

- Matthew Gault at 404 Media, which has broken scores of stories about AI-created content crowding out the real stuff, investigated its use in a “slop presidency” that shares fake images to dramatize real policies.

- Lifehacker’s Jordan Calhoun first noted the Crockett slop, and came up with a formula: “The subject is a controversial media figure, the predicate is a verb that could describe both physical violence or rhetoric, and the object is a media figure. Close it off with a button and you got a YouTube AI political video.”