The Facts

The Earth has more than enough of the metals and minerals needed for the energy transition. The trouble is, they’re in the Earth: The real bottleneck is how quickly the silver for solar panels, rare earth metals for wind turbine motors, lithium for electric vehicle batteries, and more can be mined. No amount of permitting reform or tax breaks can spur a mining boom of the scale needed to fully match supply to demand. That means prices for these minerals are almost certain to spike — and that different approaches are needed to close the gap.

Tim’s view

There are two main ways to address this problem, both of which are drawing investment and scaling up alongside the wave of new mines: Recycling and improved mine-waste processing.

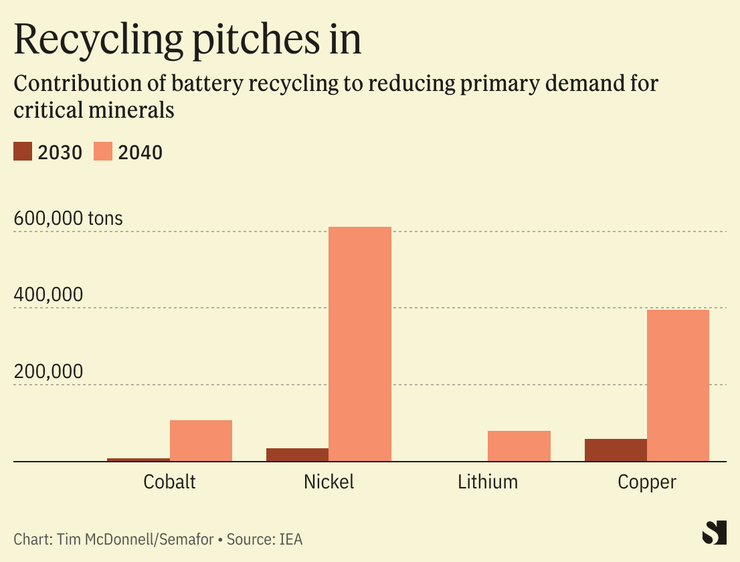

Today, electric-vehicle battery recycling is almost nonexistent, and by the same token most EV batteries and other clean tech contains no recycled minerals. That will change dramatically over the next decade as all the EVs being bought now reach the end of their life.

Unlike the fossil fuels we currently rely on, we won’t be burning the minerals that will underpin the greener economy of the future. So not only can we recycle them, we must: A recent Johns Hopkins University study concluded that the mineral production expected by 2030 falls massively short of projected demand by the U.S. and its main trading partners. Eighty times more graphite is needed, 10 times more lithium, 30 times more cobalt, and twice as much nickel. If China and other suppliers are counted too, lithium and cobalt supply would still meet only half of global demand by 2030, the International Energy Agency projects.

Know More

By 2030, 1.2 million EV batteries will be available for recycling, according to the International Council on Clean Transportation, reaching up to 50 million by 2050. Depending on how efficiently the minerals in those batteries can be recycled, they could provide anywhere from 5-30% of the minerals needed for battery manufacturing globally by the mid-2030s.

“We need to do urban mining to supplement the earth mining,” said Steve Cotton, CEO of Aqua Metals, a Nevada-based battery-recycling company that was founded with a technology to more cleanly recycle traditional lead acid batteries and is now aiming to pivot to EVs.

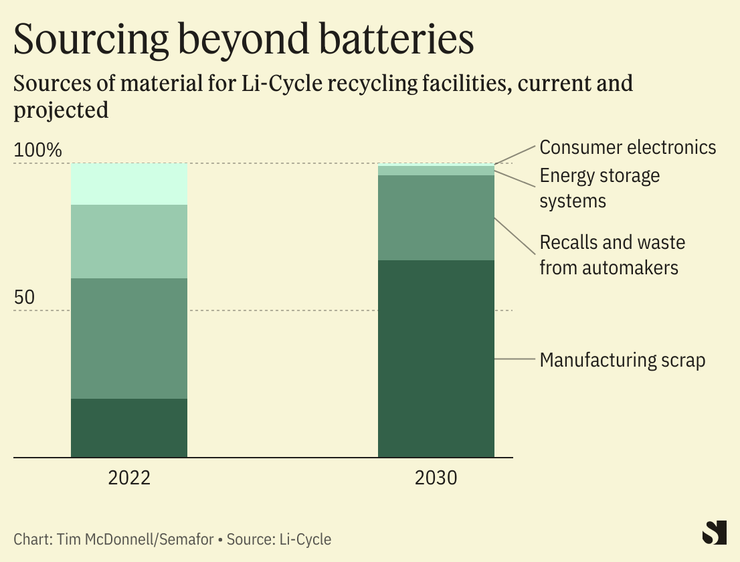

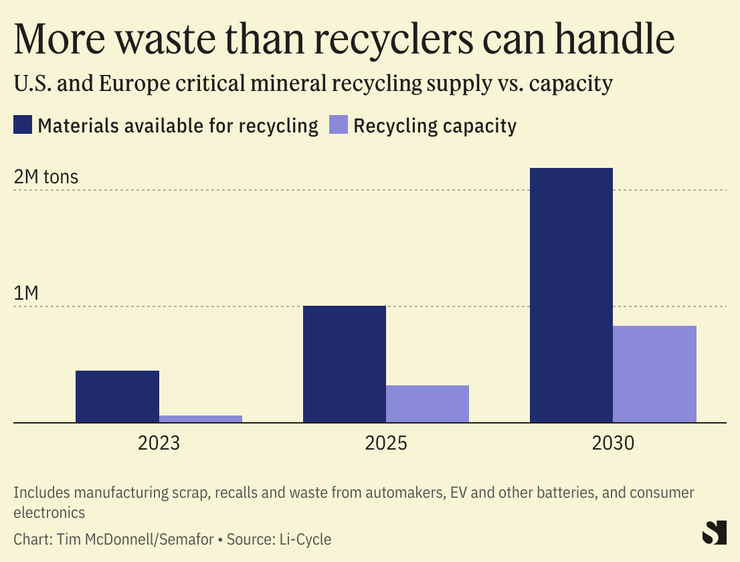

Companies like Aqua aren’t waiting for the deluge of old EVs to start scaling up. They’re already able to tap into existing waste streams, including scrap from battery manufacturers, as their feedstock. Toronto-based Li-Cycle won a $375 million loan from the U.S. Department of Energy in February to build a recycling facility in New York, supplementing four existing facilities in the U.S. and Canada. For now, battery manufacturing scrap and waste from automaker factories are the main sources of supply. Once more EV batteries start to flow in, the company expects its New York facility could become one of the largest sources of lithium in the U.S.

In fact, as Tesla and others continue to build battery “gigafactories” in the U.S. and Europe, the recycling industry will be overwhelmed with material, according to Li-Cycle projections. Automakers themselves are helping the industry catch up. Li-Cycle has a partnership with General Motors. Another recycling startup called Redwood, founded by a former Tesla executive, has raised more than $1 billion from partnerships with Ford Motor, Toyota, Volkswagen, and Volvo.

The View From Arizona

Rising mineral prices are causing some mining executives to take a second look at piles of waste at existing mines that were previously considered too low-concentration to bother with.

In 2019, at the Pinto Valley copper mine in Arizona, Jetti Resources became the first company to commercialize a process for extracting copper from low-grade ore that was cost-effective enough to justify, using acid and a proprietary chemical catalyst. Productivity at the mine doubled within a year, and has stayed at that level since, CFO Hugo Schumann said. The company subsequently rolled out its technology at a second copper mine in Arizona and is working on a third in Chile.

More than half of the world’s remaining copper is locked in low-grade deposits and waste like what Jetti works on, so leaching could go a long way toward addressing a looming global copper shortage. Other minerals, such as cobalt and nickel, could also be recovered from mine waste with a version of leaching that uses microbes.

Room for Disagreement

Recycling and improved leaching will narrow the gap between mineral supply and demand, but they won’t close it, especially in the near future. A 2022 paper by Danish energy economists concluded that a shortage of cobalt, for one, is practically inevitable before the mid-2030s even in the most optimistic outlook for recycling.

Notable

The Biden administration approved what will likely become the largest lithium mine in the U.S. on Wednesday. Meanwhile, dozens of other prospective mineral mines in the U.S. are being held up by legal challenges, the Associated Press reported.