The News

India is pioneering a strategy to shield its 1.4 billion people from increasingly scorching heat — a potential blueprint for low-income countries facing the same climate-induced challenges. If it works.

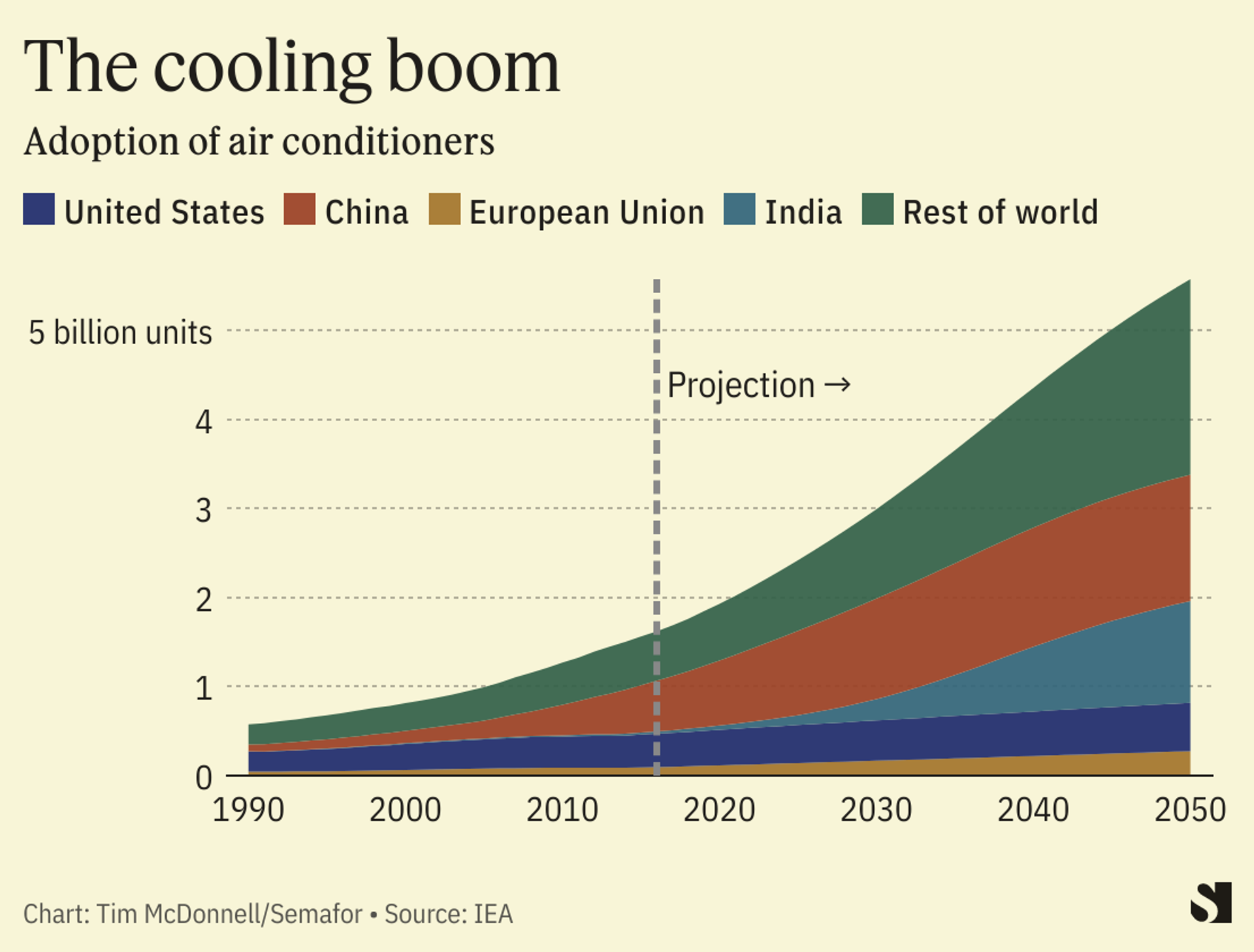

India already faces some of the longest and most brutal heat waves on record, and scientists expect this trend to worsen in future. But with average annual incomes barely above $2,000, Indians cannot afford to solve their problems with air conditioners alone.

The government’s India Cooling Action Plan is a first-of-its-kind attempt to recognize rising temperatures as a systemic challenge, proposing both high- and low-tech solutions such as tougher energy-efficiency standards and white-painted “cool roofs” to reduce the internal temperatures of buildings.

Lou’s view

The ICAP is among India’s hugely ambitious targets. Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s government wants to have 500 GW of total installed renewable-energy capacity by 2030, and become net zero by 2070 — a stretch given that various types of coal alone make up around 51% of its current energy mix.

But these grand statements are usually paired with the word “aspirational,” which cynics see as an open concession that they may never materialise. Previous renewable targets have been missed, there is no hard data on how the cooling plan is progressing, and no detailed steps to get to net zero.

Multiple sources have told me that the climate action plan for New Delhi itself — the megacity perhaps most exposed to the threat of heatwaves — has languished at the draft stage for several years.

That’s part of the disconnect I often see here in India: The country’s plans, when they are issued, are aggressive. But when it comes to implementation, they too often fall short. So far, this is what is happening to the ICAP.

“The high level vision seems good,” one expert told me, on condition of anonymity, “but when you dig into a lot of the details, one comes up with lots of hollow shells.”

Know More

India faces the possibility that a combination of extreme heat and humidity — known as a wet bulb scenario — could push the limits of human survivability. According to the consultancy McKinsey, up to 200 million people in India’s urban areas will be exposed to the risk of a lethal heatwave by the end of the decade, a number that will increase to up to 480 million by 2050.

The Western approach to cooling was “all about conditioners” says Satish Kumar, executive director of the nonprofit Alliance for an Energy Efficient Economy and one of the architects of the national cooling policy launched in 2019. But for India, “it’s much more complex than that.”

India already has the world’s highest annual cooling needs, far more than China and the U.S. combined, and the International Energy Agency projects that by 2040, electricity demand for cooling will increase sixfold.

To mitigate the demands on the grid, Indian planners have improved energy standards for fridges, air conditioners, and — crucial in India for the hundreds of millions who cannot afford either — ceiling- and wall-mounted fans. Higher efficiency fans alone could reduce the country’s peak power demand by up to 10 GW, a significant chunk of overall demand of 230 GW. They are also promoting a raft of other low-tech measures, including “cool roofs,” new rules on the directions buildings point in and their ratios of windows to doors, as well as the installation of blinds on windows.

Officials also want to expand training of maintenance workers to help ensure appliances don’t degrade, while at the same time offering well-paid, technical employment to a raft of workers who need not be fully literate, a key stumbling block in India.

Small, low-tech interventions are how you achieve scale in a country like India, as well as in many other developing countries, Kumar says.

Room for Disagreement

India can still make its cooling plan work, two experts wrote in EnergyWorld, so long as it ensures new buildings meet high energy-efficiency and insulation standards, prioritizes renewable energy, and gives more power to its states to devise appropriate local solutions.

The View From Miami

One way that several cities around the world have honed low-tech responses to heat waves is by appointing dedicated bureaucrats to the task. Miami was the first city in the world to appoint a chief heat officer in 2021. Her job entails a mix of public communication and outreach on heat-related health risks, as well as urban planning and landscaping to improve access to shade and air-conditioned public spaces like malls. Half a dozen cities worldwide have followed suit, most recently Dhaka, which appointed the first heat officer in Asia last week.

Notable

- India’s efforts have not matched its promises, analysts say. In a 2021 report, the nonprofit International Forum for Environment, Sustainability & Technology said that the cooling plan lacked a concrete implementation timeline as well as mechanisms to monitor progress and enforce action.