The Facts

Climate change could curdle the balance sheets of global meat and dairy companies.

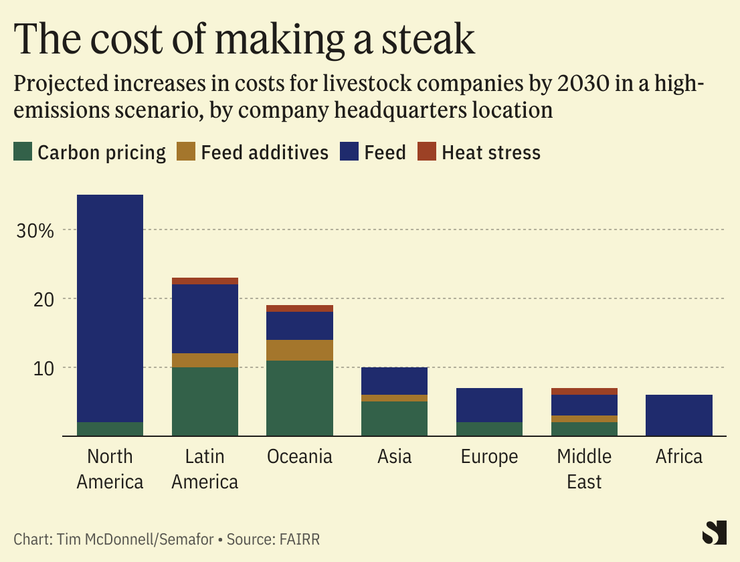

By 2030, the top 40 global livestock companies could see profits fall collectively by nearly $24 billion, according to a recent report by a shareholder advocacy group. Causes include heat stress on animals and rising feed crop prices, as well as the financial toll of carbon pricing and anti-deforestation measures.

Half of those companies — including well-known giants such as JBS and Tyson, along with others headquartered in Brazil, China, and elsewhere — are on track to be operating at a loss by 2030, the report said.

Tim’s view

Investors frequently raise concerns about the financial impacts of climate policy on both energy companies and the banks that finance them, and some are demanding these companies reduce their reliance on fossil fuel revenue to protect their long-term profitability. But the livestock industry has been slow to plan for how global warming and policies to prevent it will affect its bottom line, leaving their shareholders holding the bag. It’s not dissimilar to how shareholders of oil and gas companies could wind up on the hook for production assets that get “stranded” by climate policy.

“The livestock sector is far behind other sectors, given the exposure they have to climate risks,” said Erika Susanto, director of ESG research at the FAIRR Initiative, the London-based research outfit that produced the latest report. “The financial impacts will be quite material.”

Know More

The FAIRR analysis is based on information from companies’ disclosures about which types of animals they raise or process, where they do so, how much feed they use, and other factors, combined with models of future climate change.

Drought and rising temperatures are likely to cut the global grain supply, for example, and livestock produce less meat and milk in hot weather. The analysis also incorporates a forecast of carbon pricing. Livestock emissions are not currently taxed anywhere in the world, but Europe will soon tax emissions from fertilizer production, which will raise the cost of animal feed. And in Latin America and elsewhere, livestock companies could face an indirect form of carbon pricing either through policies that restrict deforestation (and thus limit the availability of grazing land), or through the market for voluntary carbon offsets, which in Brazil is already making it more profitable for landowners in some areas to conserve forests rather than clear them for cattle.

JBS and Tyson, according to the analysis, are on track to net nearly $5 billion less in profit in 2030 than today, mostly due to rising feed costs. Marfrig and Minerva, two of Brazil’s biggest livestock companies, are on track to see profits fall by $1-2 billion. JBS, Tyson, and Marfrig declined to comment for this story. Minerva shared a strategy outline that says the company is working to diversify the geographic distribution of its assets as a hedge against climate impacts.

There are other steps these companies could take to mitigate their exposure to climate risk, FAIRR’s Susanto said, including diversifying their sources of grain, insuring animals against climate damages, and switching to breeds of livestock that are better adapted to heat stress. They should also push more to cut emissions to minimize exposure to future carbon taxes. But of the 40 companies FAIRR assessed, only 11 have published a plan for mitigating climate risk.

Rebecca White, an ESG analyst at Newton Investment Management, said that mainstream asset managers are starting to pay closer attention to climate risks in the livestock industry, and could drop shares in companies that aren’t doing enough.

Room for Disagreement

Prospects for carbon pricing are a source of significant uncertainty in FAIRR’s model. Even in jurisdictions like China and the EU, where carbon pricing for some sectors is in place, prices are still too low to make much of an impact on a company’s operations. Carbon taxation remains politically infeasible in the U.S., Brazil, and other major livestock markets. And the voluntary carbon market would need to scale up enormously to put a major dent in deforestation. A study in April estimated that it would cost up to $130 billion to fully compensate global livestock and agriculture producers for their loss of access to land if all deforestation were halted immediately.

The View From New Zealand

One exception to the carbon pricing trend is New Zealand, which in October last year became the first country to include the agriculture and livestock sectors in its national emissions cap-and-trade system. That policy will take effect by 2025, with the aim of cutting methane emissions 10% below 2017 levels by 2030 and in half by 2050. More than 50% of the country’s total greenhouse gas footprint stems from these sectors.

Notable

- Artificial intelligence could help. A nonprofit in Brazil is using AI-assisted processing of satellite images to predict where deforestation is most likely to occur, giving authorities more time to intervene. And startups like ClimateAi are developing AI software that livestock companies can use to anticipate climate changes and their financial impacts.

Correction: An earlier version of this story misidentified the ESG analyst at Newton Investment Management. She is Rebecca White, not Natalie.