The News

The Biden administration released new guidelines Tuesday on Inflation Reduction Act tax credits for the production of low-carbon aviation fuel, handing a win to the farming and airline industries but opening a rift with environmental groups.

The new rules effectively allow much more corn-based ethanol to qualify as a sustainable aviation fuel (SAF), which the European Union, for example, does not allow. They could help spark investment into SAF production facilities that has been stalled up to now. The Biden administration’s goal is to increase SAF output 20-fold by 2030 to an equivalent of 10% of current US aviation fuel demand. Corn will have to be a major contributor to the SAF supply — alongside waste oil, captured CO2, and other feedstocks — if the airline industry is to have any hope of reaching that goal, United Airlines’ chief sustainability officer Lauren Riley told Semafor.

“It will be hard to get to those volumes based on the pace of change that we’re seeing,” Riley said. “That’s why clear guidance on [the SAF tax credit] is really important, so that we can determine what to do in the few years we have left.”

In this article:

Tim’s view

It’s not too surprising that the US would take a relatively permissive approach to SAF carbon accounting, given the powerful political influence of Big Corn. But with these rules, the administration has set a challenge to the ethanol industry: to pivot to a new, sorely needed role in the energy transition without actually increasing its environmental impact. At the same time, by agreeing to subsidize corn for SAF, Biden is essentially doubling down his bet on electric vehicles, since the extent to which corn-based SAF becomes a climate hazard is closely linked to how quickly EVs can displace demand for gasoline.

The SAF tax credits are worth up to $1.75 per gallon, provided SAF manufacturers can prove their product’s emissions, including any associated with growing biofuel crops, are not more than half those of conventional fossil-based fuels. They create a new financial incentive for farmers to adopt practices like no-till farming, planting cover crops, and using higher-efficiency fertilizer that reduce or draw down emissions. It also incentivizes ethanol producers to adopt carbon capture technology. But the new rules under-estimate the emissions associated with converting more land to cornfields, as SAF competes with food and transport fuels, said Dan Lashof, US director for the World Resources Institute.

“Powering planes with crop-based biofuels is anything but sustainable,” he said, and will “benefit wealthier air travelers at the expense of average consumers who will pay more for food.” The new rules “put the U.S. aviation industry out of step with its international competitors and made its own climate protection goals harder to achieve.”

But it’s not clear how intense that competition will really be. Ethanol demand for road transport is expected to fall 14% by 2030, mostly because of EV adoption, according to Coco Zhang, vice president of ESG research at Dutch bank ING. SAF, she said, could be a “lifeline” for ethanol producers and the corn farmers that supply them, with airlines easily able to absorb what drivers don’t want. With a strong supply of corn-based ethanol, the US could provide half of the global SAF supply, and possibly become a net exporter, she said.

While road transport demand for ethanol is falling, US corn yields per acre are increasing. That leaves room to use more corn for aviation fuels without increasing agricultural water consumption or causing land conversion, said Tom Michels, United’s director of government affairs: “Our expectation is that as airline demand grows, it’s not really adding demand, but basically just diverting the existing supply into a different fuel tank.”

Zhang pointed out that the climate impact of corn-based SAF hinges a lot on the US presidential election: While a second Trump administration would most likely continue a favorable stance toward ethanol, it would likely roll back incentives for EVs, thereby putting more pressure on the ethanol supply and raising the odds of land conversion emissions.

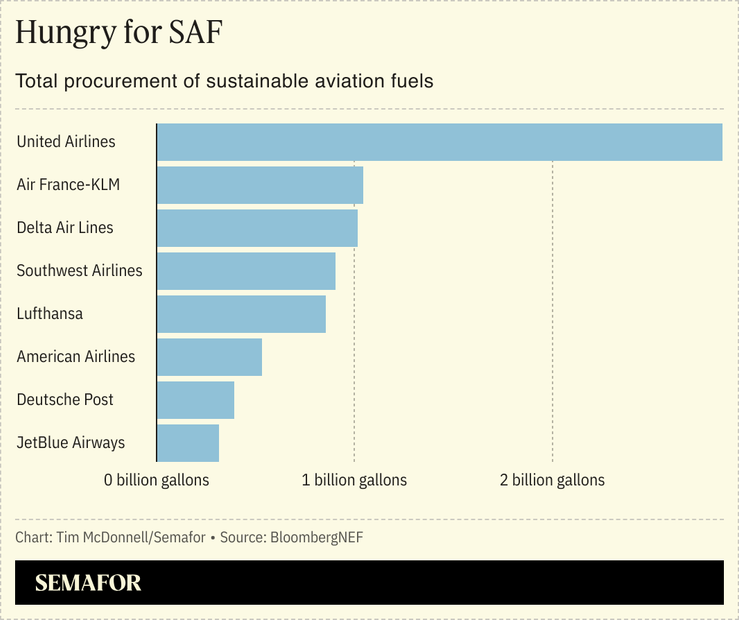

Riley, who has led United to be the industry’s top SAF buyer, said SAF will have to come from a wide range of feedstocks, and she’s happy to let the market dictate how much comes from corn versus other sources. The more important thing, she said, is to get ahead of her competitors in building up a stockpile of SAF as a hedge against an inevitable, expensive carbon crackdown by governments.

“Carbon pricing will happen,” she said. “When it does, those companies that have prepared for a transition to low-carbon alternatives will be more competitive.”

Room for Disagreement

To some extent, whether or not these rules are favorable to corn-based SAF is beside the point. That’s in part because they expire at the end of this year and will need to be revisited after the election. And no matter what the rules say, Wall Street still sees SAF production as “a very risky field,” Michels said. The nascent industry’s biggest challenge is financing commercial-scale factories that use new, unproven technology, especially since no airlines are willing to sign long-term offtake agreements that would set bankers at ease but would require airlines to make a commitment none are yet willing to make. Whether it includes corn or not, the best thing for SAF, Michels said, would be for Congress to extend the lifetime of SAF tax credits up to a decade, like it did for wind and solar credits.

The View From Europe

European Union regulators said Tuesday that they are investigating 20 unnamed European airlines for possible greenwashing, including overstating the climate benefits of both SAF and carbon offsets. Europe has an ambitious target for SAF to provide 70% of aviation fuel by 2050. But the EU has so far been much more strict than the US about what kinds of carbon-cutting solutions it will allow airlines to practice, which could create complications for companies operating in both regions.