The News

Chinese wind turbine makers, already industry leaders, are about to fast-track their global expansion, key industry players say.

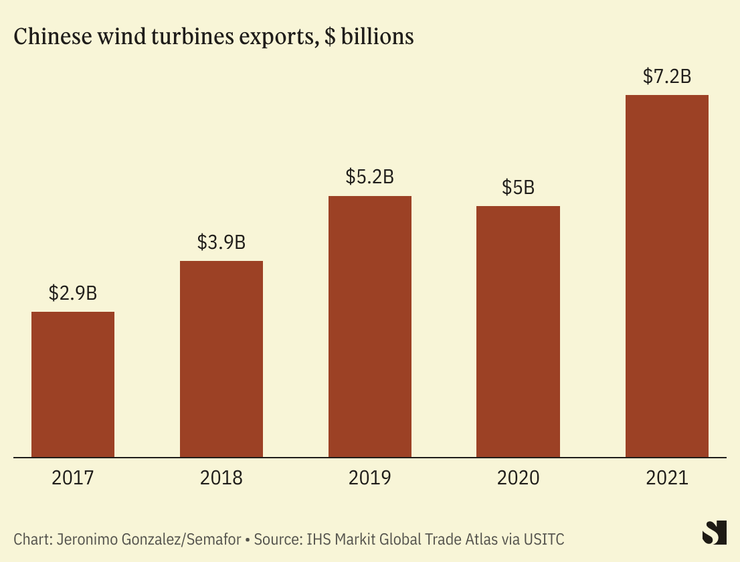

After spending years developing a range of products and building global supporting networks, Chinese companies are on the cusp of an “exponential growth in exports,” a senior member of the country’s main wind industry trade body told me.

Overseas orders signed by Chinese wind turbine manufacturers in the first quarter of this year alone added up to nearly 2 gigawatts — almost their total export volume in 2022 — according to the Chinese research firm Windmango.

Western wind turbine giants have been hit by an array of obstacles, including COVID-19 lockdowns, supply chain disruptions, and spiking costs for commodities and shipping. Chinese companies, on the other hand, have weathered the storm relatively well on the back of robust home-based supply chains and the nation’s dominance in steel production and raw materials.

Xiaoying’s view

Chinese companies already dominate the global solar-panel market, but while the country’s wind-turbine manufacturers occupy around half of the overall global onshore and offshore market and hope to grow that share, the path to expansion abroad is far more complicated.

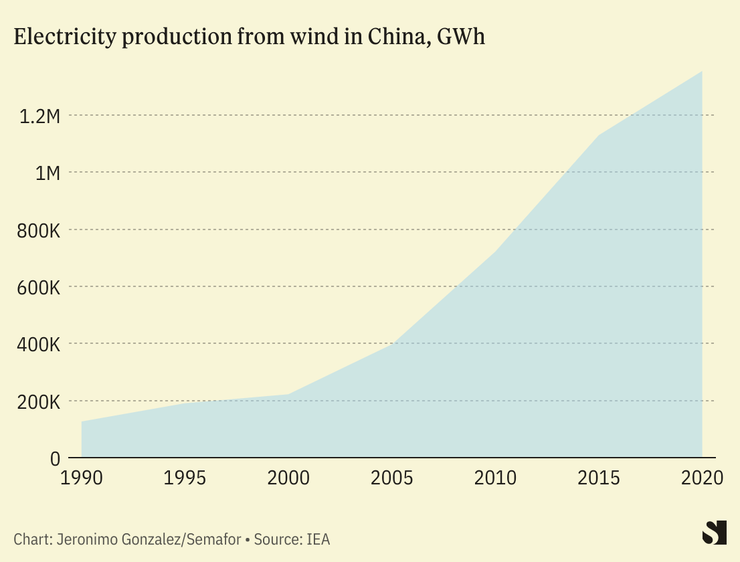

China has had the world’s largest installed capacity for wind power since 2010, and is now home to more than one-third of the world’s wind power capacity. And it’s still growing: In 2021 and 2022, China’s cumulative growth in wind capacity was 3.6 times greater than that of the United States and 7.3 times greater than that of Europe over the same period.

Despite that fast growth, Chinese wind turbine makers still see opportunities abroad, although not necessarily in Western markets, where complicated laws, industry regulations, and what Chinese officials described as “trade barriers” have posed obstacles for Chinese firms’ expansion.

In the short term, most of their overseas orders will likely come from emerging economies in Southeast Asia, the Middle East, Eastern Europe, and Central Asia, where Chinese companies already have a presence due to Beijing’s Belt and Road economic program.

Gu Limin, a senior director at Envision Energy, one of China’s biggest wind turbine manufacturers, told me that he expected Chinese firms’ global market share to “be higher and higher in the next few years.” Offshore wind power, in particular, presents “huge opportunities,” he said.

The differences between the wind and solar industries, however, are instructive. Solar is a highly commoditized industry, shipping is relatively easy, and products are standardized. Wind turbines are more project-specific and harder to transport.

Chinese wind manufacturers “not only need to be familiar with the policies and legal frameworks of different countries but also participate in many other steps, such as financing, certification, logistics, and installation,” Qin Haiyan, secretary-general of the Chinese Wind Energy Association told me.

This is one of the obstacles for Chinese companies entering European and U.S. markets, but they have made some headway, Qin noted. For example, Mingyang, a major manufacturer, became the first Chinese company to supply wind turbines to a European offshore wind farm after helping build the Beleolico project off southern Italy.

Know More

Chinese companies boast what one industry insider dubbed a “landslide” price advantage over their Western counterparts. Their products cost less than half — and sometimes as little as a quarter — of Western equivalents.

One driver for the low cost is China’s production scale. According to Qin, more than two-thirds of the world’s wind turbines are manufactured in China, including those produced for foreign brands. Chinese firms also benefit from complete and concentrated domestic supply chains and clear government policies. To some extent, these advantages at home would be partially — but not entirely — negated abroad.

Goldwind, China’s largest wind turbine manufacturer, puts the industry’s success in context. It began life as a state-affiliated research institute in Xinjiang, a wind energy hub in western China, before being privatized in 1998. Like its domestic competitors, Goldwind witnessed a decade of breakneck growth from 2005 when Beijing threw its weight behind the renewables manufacturing industry.

Now, it has more than 10,000 employees around the world, is listed on the Shenzhen and Hong Kong stock exchanges, and last year sold wind turbines with a combined capacity of 13,870 megawatts — equivalent to about half of the U.K.’s entire wind power capacity. In the past few months, the company has inked major deals in Brazil, Vietnam, North Macedonia, and Uzbekistan.

Room for Disagreement

Worsening geopolitics pose obstacles to Chinese companies. In 2021, Texas blocked the development of a wind farm owned by a Chinese billionaire, citing an alleged national security threat. Late that year, the EU imposed anti-dumping tariffs on imported Chinese turbine towers after an investigation found they were being sold at “artificially low prices.”

Chinese companies also have their own disadvantages compared to Western firms, such as “a much smaller international presence and resulting business networks and contacts, as well as far less globalized supply chains,” Cosimo Ries, a renewable energy analyst at the consultancy Trivium China, told me.

The View From Europe

Major industry players told the Financial Times in September that European wind turbine manufacturers were “financially struggling and cutting jobs.” And last year, five Western firms warned in an open letter to the European Commission that they were “losing ground” to Chinese companies.

“It’s on price and financing conditions that the Europeans are really, really struggling,” when pitted against Chinese firms in third markets, Pierre Tardieu, Chief Policy Officer at WindEurope, a trade group, told me.

To address some of the concerns, European policymakers have taken steps, such as with the proposed Net Zero Industry Act, aimed at scaling up the manufacturing of clean technologies in the EU. “This is a dynamic situation,” Tardieu noted. “Nothing is closed.”

Notable

- An overseas expansion by Chinese companies — particularly Mingyang — could help develop larger turbines and drive prices lower, Norman Waite, an energy financial analyst, explained in a report published by the Institute for Energy Economics and Financial Analysis.