The News

A new low-carbon fuel just got a major vote of confidence from investors — but it’s still years away from making a dent in the energy transition.

Denver-based startup Koloma closed a $245 million Series B fundraising round last Friday, a big haul by climate tech standards. The company is developing technology to find and tap underground reservoirs of naturally occurring hydrogen gas. The idea is that geologic hydrogen — also known as “white” or “gold” hydrogen in the industry’s rainbow-inspired jargon — could be mined at lower cost and with a lower carbon footprint than hydrogen produced from fossil fuels or even from renewable electricity.

In this article:

Tim’s view

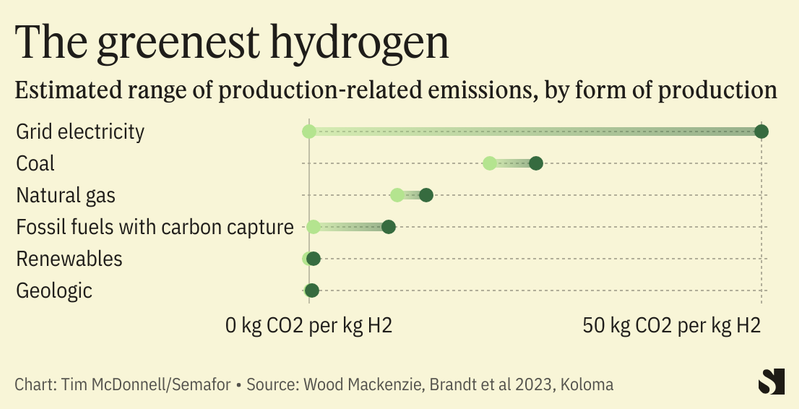

Hydrogen is a kind of magic key in the energy transition, a fuel that could replace hard-to-electrify molecules combusted by factories and commercial ships and vehicles. But today its rollout is complicated by a basic tension: Existing methods of hydrogen production can be cheap, but have little or no benefit for the climate over traditional fossil fuels, while truly low-carbon hydrogen is very expensive. Over the next decade, as regulators ramp up pressure on industrial energy users to decarbonize, more will be willing to pay a premium for verifiably clean hydrogen. Businesses that can produce it cheaply will be in position to pocket a windfall — hence the big bet on Koloma.

The company is the most well-funded of a small cohort of startups chasing a natural resource that until now has had no commercial value. Geologists believe subsurface hydrogen is extremely abundant: According to the U.S. Geological Survey, if just 2% of estimated global underground hydrogen reserves could be tapped, it would be thousands of times more than the projected 2050 demand for low-carbon hydrogen in a net-zero world. Hydrogen deposits also appear to be widely distributed, with evidence found in the U.S., Europe, Australia, the Middle East, and elsewhere. Hydrogen is a tiny molecule, so trapping it isn’t easy. But a completed hydrogen well would have virtually none of the land use, water, or energy demands that significantly complicate and raise the costs of other forms of hydrogen production.

In an interview, Koloma co-founder (and former NASCAR racer) Paul Harraka said the company sees itself as a technology purveyor more than a mining company per se, using its newly-raised capital to expand its Ohio labs and refine its inventions, which are essentially the picks and shovels that other companies might use for hydrogen mining. That business model sounded lucrative to storied Bay Area venture capital firm Khosla Ventures, which led the fundraising round.

“If these guys have the technology to find and extract geologic hydrogen, it’s going to be a huge, huge deal,” Samir Kaul, Khosla’s managing director, told Semafor.

Geologic hydrogen mining can produce greenhouse gas emissions, since there is often methane trapped in the same reservoirs that can leak out. But its carbon footprint is close to zero, making it potentially the most climate-friendly flavor of hydrogen available. A Wood Mackenzie report this week argued that the global hydrogen market is poised to split, with greener forms commanding a premium and flowing mainly to Europe, where demand will be highest.

Kaul said the size of Koloma’s fundraising round gives the company a considerable leg up over its competitors such as Natural Hydrogen Energy, which drilled the first U.S. hydrogen well in 2019. But Harraka said it’s too soon to say when commercial-scale hydrogen mining will happen, and that in the industry’s early days, costs will still be high. That means there’s a risk that by the time geologic hydrogen production is up and running, renewable electricity-based hydrogen — which can be situated anywhere with decent wind or sunshine — will be much more cost-competitive. Kaul is happy to take that chance: “The market size is so big that it’s okay to wait a little bit.”

Room for Disagreement

Even though geologic hydrogen is geographically distributed, its biggest problem is still its location: “where Mother Nature put it,” as Harraka said. That’s not very helpful if the goal is to feed it into industrial hubs, since transporting hydrogen requires either costly pipeline networks or ships that can carry it as liquid ammonia. Distribution and the ammonia process also produce emissions, which could erase geologic hydrogen’s climate benefit. Koloma is focused on finding deposits near likely demand centers, Harraka said; Cemvita, another geologic hydrogen startup, is addressing the location problem by using proprietary biochemistry to convert residue inside abandoned oil and gas wells into extractable hydrogen.

The View From Mali

The only commercial hydrogen mining operation today is in Mali, where in the late 1980s geologists looking for water hit a hydrogen stream instead, which is now used to power nearby villages.