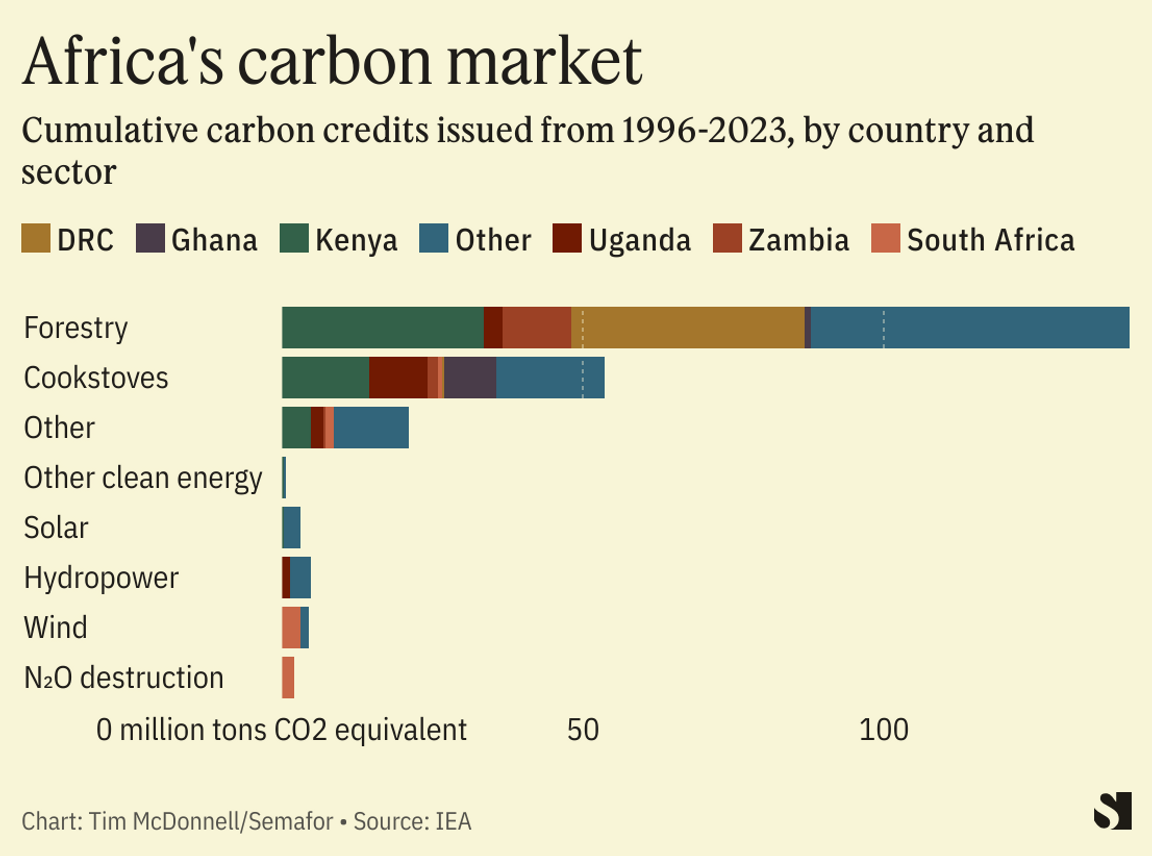

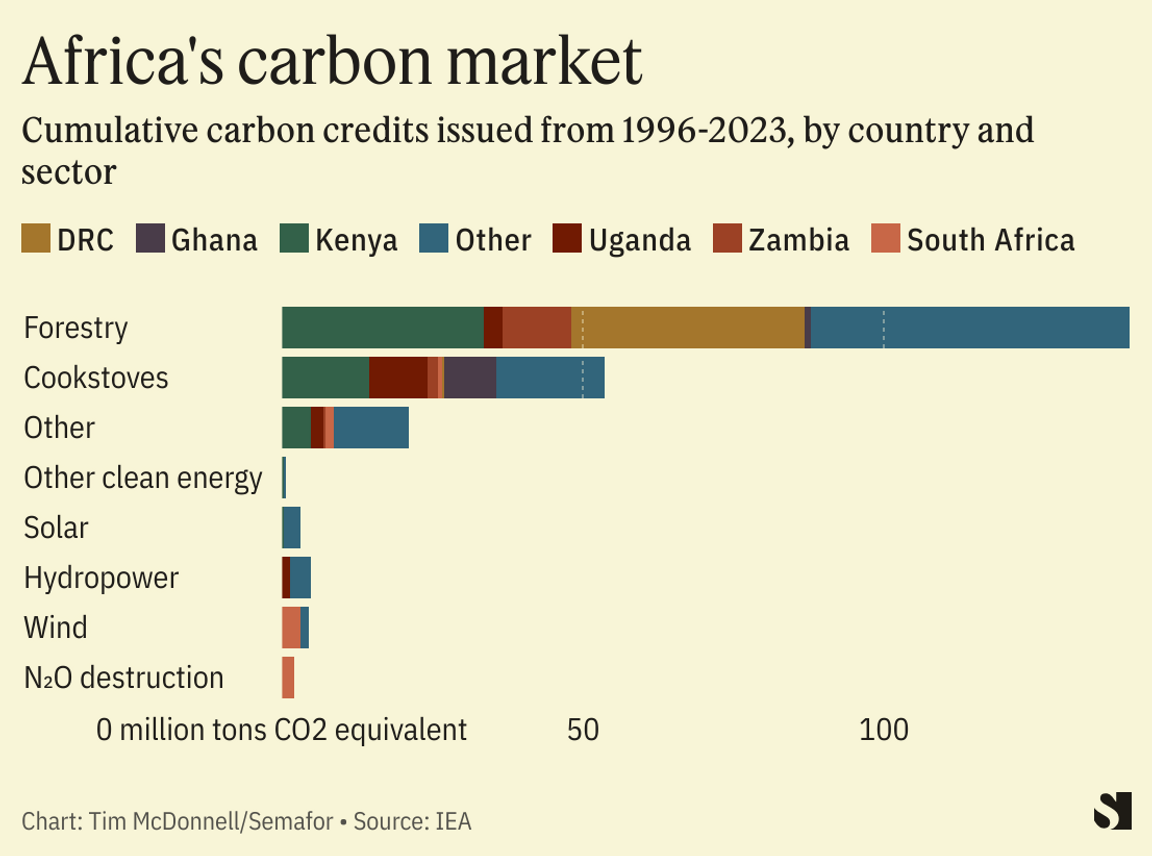

REUTERS/Monicah Mwangi REUTERS/Monicah MwangiBy Tim McDonnell THE NEWS A major climate summit in Nairobi this week zeroed in on how Africa can raise the tens of billions of dollars it needs to adopt clean energy and adapt to the impacts of climate change. One option drawing an increasing amount of attention, money, and criticism: Selling carbon offsets. On Monday, an investor group from the United Arab Emirates said it would buy $450 million in carbon credits via the African Carbon Markets Initiative, a nonprofit launched last year to facilitate the sale of credits derived from Africa-based carbon-cutting projects. A separate group led by HSBC Asset Management committed to buy $200 million in credits from ACMI. Africa-based carbon projects — including renewable energy, forest conservation, replacing charcoal cookstoves with clean alternatives, among others — could be “an unparalleled economic goldmine,” Kenyan President William Ruto said in a speech Monday. “GDP is about capitalizing on what you have,” he said. “We have the carbon sinks that serve the world.” TIM’S VIEW On the surface, carbon credits may make sense as a way to raise climate finance for African countries, especially since other sources, whether via private investors or foreign aid donors, are far behind where they need to be. But the existing carbon market is riddled with accounting and social justice problems, and requires more stringent oversight to avoid becoming a contributor to the climate crisis rather than a solution to it. Africa has a huge climate finance deficit. The continent requires at least $250 billion per year in private investment and foreign aid to beef up its energy system and address climate impacts, but currently receives just 12% of that, according to the Climate Policy Initiative, a U.S. think tank. African countries draw just 2% of global annual investment in clean energy, in part because Western investors see the region as a risky environment. Carbon credits could fill this gap and lower the high cost of capital for African clean energy projects by giving U.S. and European companies, and even governments, an added incentive to put their money into African climate projects: the ability to write down their own emissions. Africa-based carbon credits — predominantly from forest conservation projects — are already routinely sold to Western airlines, energy companies, and other big emitters, although they account for only about 11% of credits on the market globally, according to the International Energy Agency.  Growing that share could effectively convert Africa’s green development into one of its most lucrative export commodities. The ACMI estimates that African countries currently use less than 2% of their annual carbon credit production potential, and could raise $100 billion per year by 2050 through carbon credit sales. That idea was endorsed at the Nairobi summit by European Commission President Ursula von der Leyen and by U.S. climate envoy John Kerry. Private companies aren’t the only potential buyers: The Paris Agreement allows carbon project developers to sell credits to foreign governments that they can apply toward their national decarbonization goals. Ghana was the first country to pioneer this strategy, with a carbon credit deal with Switzerland it organized last year. According to the IEA, sovereign carbon credit sales by African countries could raise even more money than sales to companies. — For more — including a Room for Disagreement and a View from Gabon — click here. |