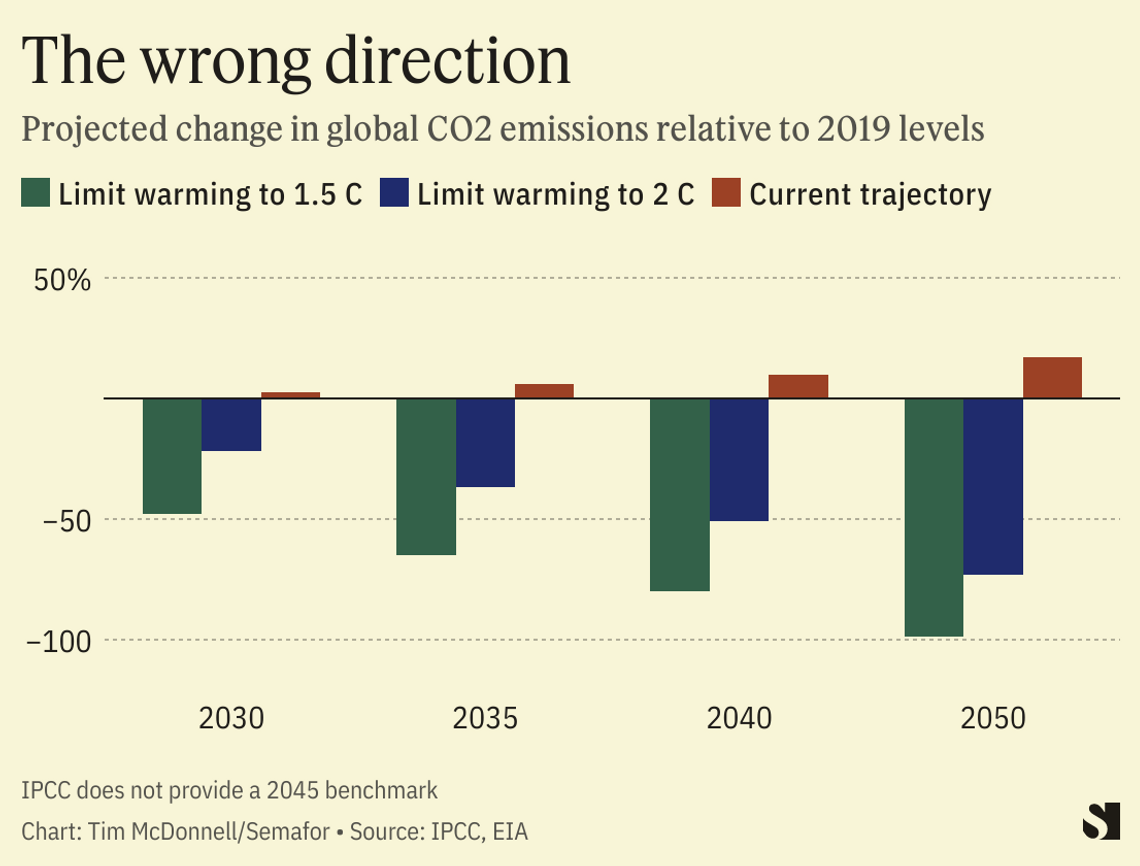

United Nations Photo/Flickr United Nations Photo/FlickrTHE SCOOP International climate negotiators are divided over key elements of a United Nations fund they’re creating to distribute financial resources from richer nations to low-income countries impacted by climate change, negotiators and observers told me this week. With eight months left before the COP28 climate summit in Dubai, two dozen delegates from a range of countries are scrambling to lay out rules for the “loss and damage” fund adopted at COP27 in Egypt last year, that summit’s biggest accomplishment. They have just three scheduled meetings before COP28, the first of which is next week in Egypt, to agree on essential details of how the fund may be accessed and where the money will come from. As talks begin, negotiators say they face steep odds of getting cash flowing soon. “As much as [the loss and damage fund] was a breakthrough, it felt like an empty wallet,” Sara Jane Ahmed, advisor to a group of finance ministers from 20 countries highly vulnerable to climate change, told me. TIM’S VIEW Some fault lines in these negotiations are familiar, while others are just emerging. Low-income countries, especially island nations, have been pushing for a loss and damage fund for years, on the theory that the high-emissions countries that have driven the climate crisis should bear more financial responsibility for the unavoidable climate impacts that are already happening worldwide and which poorer states are particularly vulnerable to. During COP27, delegates from the U.S. and EU were reluctant to agree to a loss and damage fund without a more detailed plan for how it would be capitalized, for fear of being stuck with the whole bill, and who would receive payouts. They eventually agreed once language was added mandating the fund seek “new and additional resources” beyond the traditional pool of climate finance. But they may push again now to narrow the pool of possible recipients to only the poorest countries — which would exclude most island nations — and to set a strict definition of “loss and damage” that could entangle future claims in red tape. The overall effect would be to limit the fund so that it can be covered by existing aid budgets, said Alpha Kaloga, a leading negotiator for the Africa Group, when in fact much more financing is needed. Total global aid spending is about $180 billion per year, while climate-related loss and damage is projected to exceed $500 billion annually by 2030 in developing countries alone. Instead, he said, negotiations should start from the other end of the funnel, with a wide-ranging assessment of unconventional funding streams that could be tapped straightaway. That could include sovereign debt cancellation, new taxes on fossil fuels, government-backed insurance networks, or reforming risk standards at multilateral development banks to encourage lending. If countries can agree to put all these on the table for loss and damage, he said, the fund itself can be more expansive and operationalized more quickly. Another fracture is within the G-77 developing countries grouping, which is usually unified in climate diplomacy. Expanding the loss and damage donor pool isn’t popular with some members of the bloc that are arguably next in line to pay up, including China, India, and several Gulf countries (which needless to say don’t support oil and gas taxes either). These questions won’t be easily resolved. Ultimately, the U.N. can’t compel any country to pay. But the longer the distribution of loss and damage is delayed, the more economic damages will accumulate in developing countries. QUOTABLE “If we have to borrow money every time we get hit by a hurricane, we’ll be sinking under oceans of debt long before the seas rise up.” — Avinash Persaud, negotiator on the loss and damage committee and special advisor on finance to the Prime Minister of Barbados. KNOW MORE Loss and damage has always been among the most contentious fronts in climate diplomacy, because the concept of climate reparations forces thorny debates about how to assign historic responsibility for emissions and how to quantify damages and attribute them to climate change. But this week’s Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change report emphasizes repeatedly that loss and damage is occurring today, and that it traps the poorest countries in a cycle of debt that, in turn, restricts their ability to invest in proactive climate adaptation. ROOM FOR DISAGREEMENT One problem with a loss and damage fund is that the U.N. doesn’t have a sterling track record of administering climate funds. The $12 billion Green Climate Fund, which was created in 2010 to provide grants and concessionary loans to climate adaptation and clean energy projects, is notoriously tedious for developing country government agencies to access, requiring mountains of paperwork and financial auditing handled from its central office in South Korea. In some cases, projects backed by the fund have been linked to land disputes and human rights abuses. “Many agencies don’t even engage with the GCF because it’s so cumbersome,” said Michai Robertson, research associate at the global affairs think tank ODI and a senior advisor to the Alliance Of Small Island States negotiating bloc. THE VIEW FROM DUBAI The loss and damage negotiations are an early test for Ahmed Al Jaber, the Emirati energy executive who will preside over COP28, and his chief negotiator Hana AlHashimi, who will attend next week’s meeting in Luxor, Egypt. COP presidents are meant to remain neutral, but wield a lot of control of the agenda. And as a country with ambitions to increase its oil and gas production, the United Arab Emirates has an interest in limiting the scope of loss and damage liability. NOTABLE |