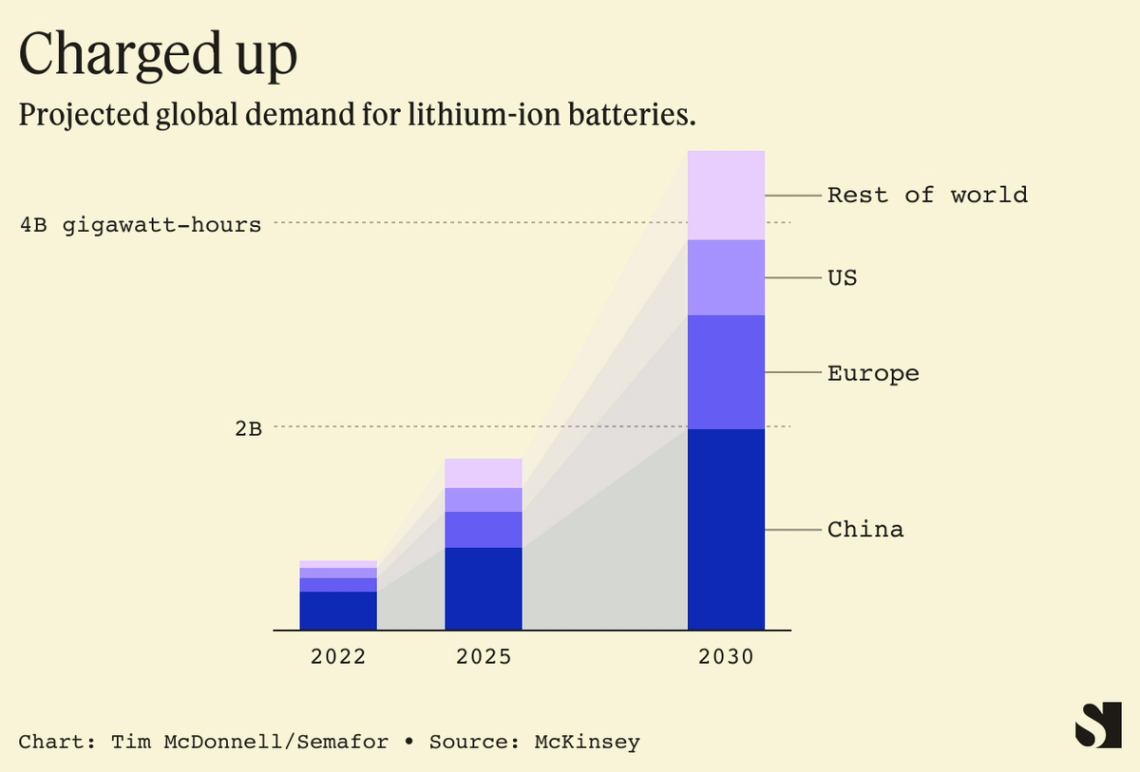

Pexels/Kindel Media Pexels/Kindel MediaTHE NEWS Climate tech investors in the U.S. are bullish on the year ahead, despite a potential looming recession and rising interest rates that could put a damper on fundraising for other startups. Those backing ventures targeting climate change are bolstered by an avalanche of new state and federal funding, largely thanks to the Inflation Reduction Act passed by Congress last year. That money will help defray the costs of scaling up manufacturing and lock in demand for low-carbon products and services. “Climate is definitely a bright spot in the tech VC world,” said Matt Petersen, president of the Los Angeles Cleantech Incubator. “All the right market signals are coming from policymakers, and we haven’t even seen the whole benefit of the Inflation Reduction Act on climate tech yet. Much of the opportunity is yet to be created.” In 2022, climate tech venture funding reached $70.1 billion, according to market data firm Holon IQ, up 89% from the year before even as overall VC funding contracted. The first few weeks of the year have already seen several multi-million dollar fundraising rounds for U.S. startups working on everything from battery recycling to solar energy storage to software for trading clean energy tax credits. European startups are also drawing high-dollar investments, and have their own raft of public funding to look forward to as EU policymakers craft a response to the IRA. TIM’S VIEW Climate tech is well-positioned at the nexus of a couple of key economic tailwinds. First there’s the $750 billion in federal loans, grants, and tax breaks made available by the IRA, and other recent U.S. legislation for clean tech R&D and the buildout of manufacturing facilities. That money is especially promising for hard-tech startups working on charging stations, batteries, and other gear for electric vehicles, and those working on low-carbon cement and other industrial processes. As for private funding, until the last few years, climate tech was the exclusive domain of a few narrowly-focused venture funds. Now the space is crowded. In addition to the growing number of traditional private equity and venture capital funds focused on climate, at least half a billion dollars have been channeled to climate tech from philanthropies since 2017. Mainstream banks and asset managers are putting together high-dollar climate tech investment funds, most recently a $1.6 billion fund announced by Goldman Sachs earlier this month and a $15 billion fund by Brookfield. The investment arms of legacy high-carbon companies, including utilities, and oil and gas majors, are also attracted to climate startups as a cost-effective means of developing the technology they need to reach their own decarbonization targets. In some cases, they have later acquired those companies, in some cases for pennies on the dollar after the startups lost value after going public, like Shell’s purchase last week of EV charging company Volta. As investors set ever-higher bars for traditional tech companies, there’s no shortage of appetite for potentially planet-saving technologies, even when profitability could be years away, said Albert Wenger, a partner at Union Square Ventures in New York: “There’s a rotation of capital away from software and into climate.” But what all this investment means for the climate remains unclear: Some of the technologies with the biggest carbon benefit per dollar, including food waste reduction and next-gen solar, remain underfunded relative to electric mobility. ROOM FOR DISAGREEMENT Given the momentum behind the global energy transition, a repeat of the climate tech bubble that tanked many early adopters a decade ago seems unlikely. But since so much cash has been plowed into startups in the last few years, and with even more coming from the IRA, a shakeout is probably inevitable soon, said Dan Goldman, managing director of Boston-based Clean Energy Ventures. “Some of these companies may not be performing,” he said. “So will they be supported by their existing investors, or are those going to say ‘We’re not throwing good money after bad.’ I think 2023 could be a year of reckoning.” That’s especially true as climate tech startups funded a few years ago start to compete directly not against legacy tech rivals but against new startups with more cost-efficient versions of similar technology, said Po Bronson, a general partner at venture capitalist SOSV. THE VIEW FROM DETROIT The peccadilloes of high-carbon legacy companies will be decisive for which climate startups rise above the pack. U.S. automakers, for example, are carefully deliberating which battery and charging technologies to use in their expanding EV fleets — fateful decisions that could transform the fortunes of an emerging company overnight and ice rivals out of the market. |