The News

THE NEWS

A new study claims to resolve a longstanding debate: Does money buy you happiness? In 2010, Daniel Kahneman and Angus Deaton, two Princeton-based economics Nobel laureates, published a study saying that it did, but only up to an income of about $75,000. In 2021, research by the economist Michael Killingsworth seemed to contradict those findings.

In the new paper, Killingsworth and Kahneman worked together to find out where their findings differed. They established that, apart from a subset of unhappier people, happiness really does increase with more wealth — or, more accurately, unhappiness decreases — even for the rich.

In this article:

Tom’s view

The idea that money can’t buy happiness is one of those counterintuitive “facts” that everyone seems to know. Partly, I suspect, it’s a comforting thing to tell ourselves, when we look at the lives of other, richer people: Sure, they might have a yacht, but are they truly happy? And it’s sneaking its way into policy, with governments buying into this idea that wealth isn’t wellbeing.

In 2019, New Zealand introduced its “wellbeing budget,” intended to boost not national GDP but national happiness. After all, what’s the point in being rich if it doesn’t make you happy? The wellbeing budget tracked measures of health, safety, environmental impacts. The idea was that what we care about is human flourishing, not cold economic growth.

New Zealand wasn’t the first — Bhutan introduced a Gross National Happiness Index as a government target way back in 2008 -– and others may follow. The U.K.’s Labour Party, expected to form the next government, has floated similar ideas. India has started measuring quality of life in its Ease of Living Index. Canada is introducing a Quality of Life Strategy.

It’s an understandable move. GDP just measures how much money is spent or earnt in a country. Senator Ted Kennedy once said that GDP “counts air pollution and cigarette advertising [but] does not allow for the health of our children, the quality of their education, or the joy of their play.”

But I’m skeptical. GDP has two major advantages. One, everyone broadly agrees what it is. Wellbeing, on the other hand, can be measured in a number of ways. A 2016 study found 99 different measures, using 196 different inputs. Which do you choose? If you want to maximize “national wellbeing,” do the different measures imply different policies?

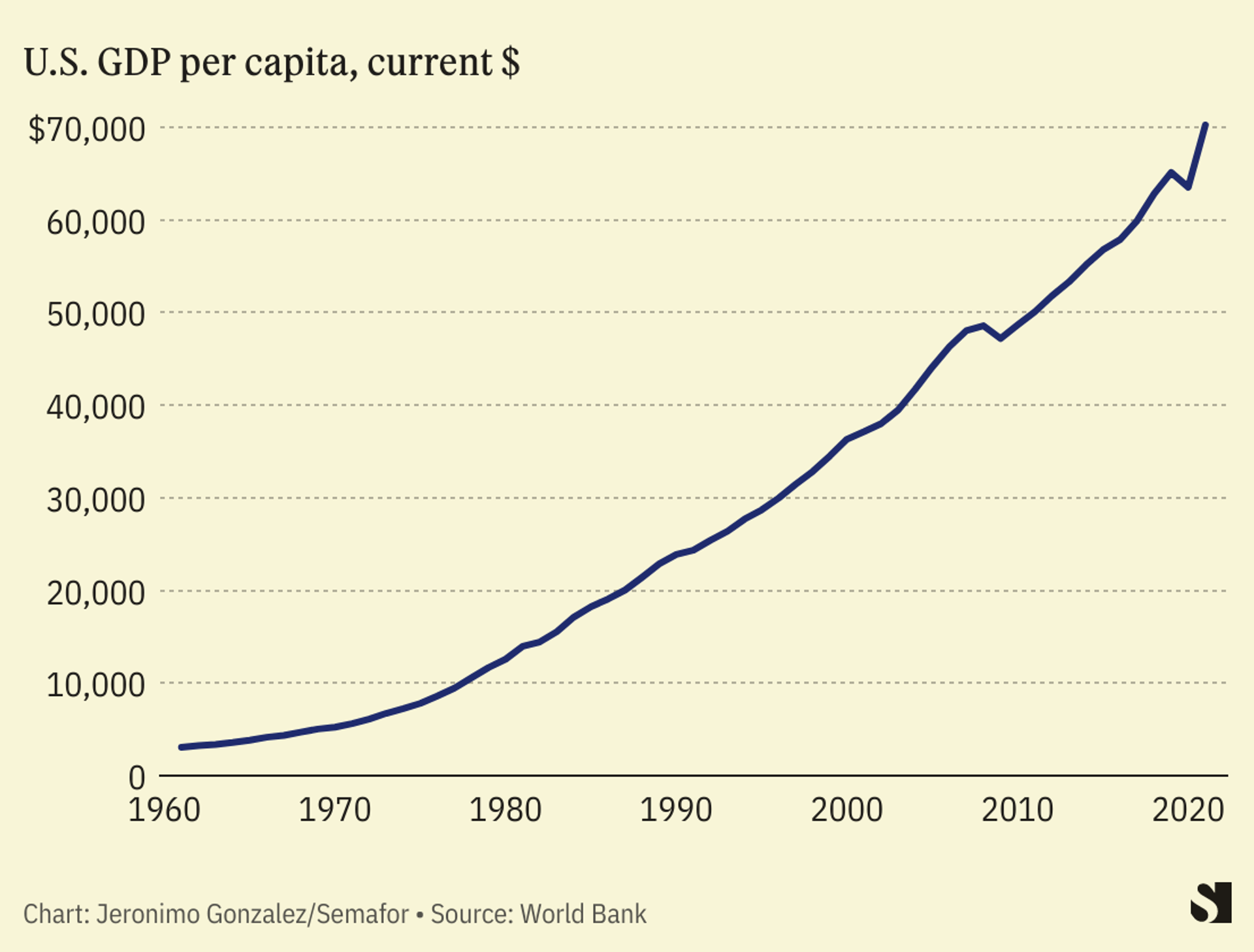

And two, GDP correlates quite well with national happiness. You can see it at a glance on a chart: Poorer countries tend to have lower reported happiness, as measured by the World Bank, while richer ones tend to have higher. It’s not uniform — some countries (Mozambique, Nicaragua) are happier than their income would predict; others (Botswana, Lebanon) are sadder. But on the whole, the story is pretty clear.

And it shouldn’t be surprising, really. Not having enough money is stressful. Money isn’t some abstract thing, it’s our ability to do things in the world: Owning a home, starting a business, paying for our children’s education. It’d be crazy to suggest that GDP is the only thing that matters, but all else being equal, if you make your population richer, you can expect that it will get happier.

And when you look at human history, almost all the things that we care about — life expectancy, education levels, health, gender equality, nutrition — have gone up as GDP has gone up. It really does seem like being wealthier is better.

We knew all that before the new study, of course. The new study simply confirms that we continue to get happier, even if we’re rich by the standards of rich countries. But it’s a nice reminder that making the world a richer place will also make it a happier one.

Know More

I’ve been talking about “happiness” as though it’s a simple thing. But researchers usually look at two major aspects of it — life satisfaction, and subjective wellbeing. Wellbeing is how you feel right now: How you’d answer questions like “Do you feel cheerful?” or “Do you feel good about yourself?” Life satisfaction is a wider-angle thing, the answer to questions like “If you lived your life over again, would you change very much?”

They don’t always go up together. People who have been made unemployed are often likely to report that their life satisfaction is down. But their subjective wellbeing sometimes goes up, because work isn’t always fun. Conversely, new parents often report reduced wellbeing, because having a toddler is rough. But their life satisfaction often goes up, because kids can add meaning to some people’s lives.

Lots of other things influence both aspects. The most crucial one is probably our genes: We are genetically predisposed to optimism and pessimism, happiness and sadness. At least 50% of the variation in people’s reported happiness scores, both wellbeing and life satisfaction, can be explained by genetics. Another is age: We get sadder as we age, on average, up until our middle years, when our happiness starts to go up again.

Room for Disagreement

GDP skeptics worry that economic growth is bad for the environment: That we can’t have infinite growth on a finite planet. That’s the thinking behind the “degrowth” movement. The good news is that economic growth is slowly decoupling from resource use and carbon emissions, even accounting for “offshoring” of carbon-intensive industries.

Notable

- The science journalist Ehsan Masood, author of GDP: the World’s Most Powerful Formula and Why It Must Now Change, talked to the Atlantic journalist Helen Lewis about GDP’s shortcomings as a measure of progress.