The News

Starting a decade ago, a generation of new-money billionaires rode to the rescue of American journalism:

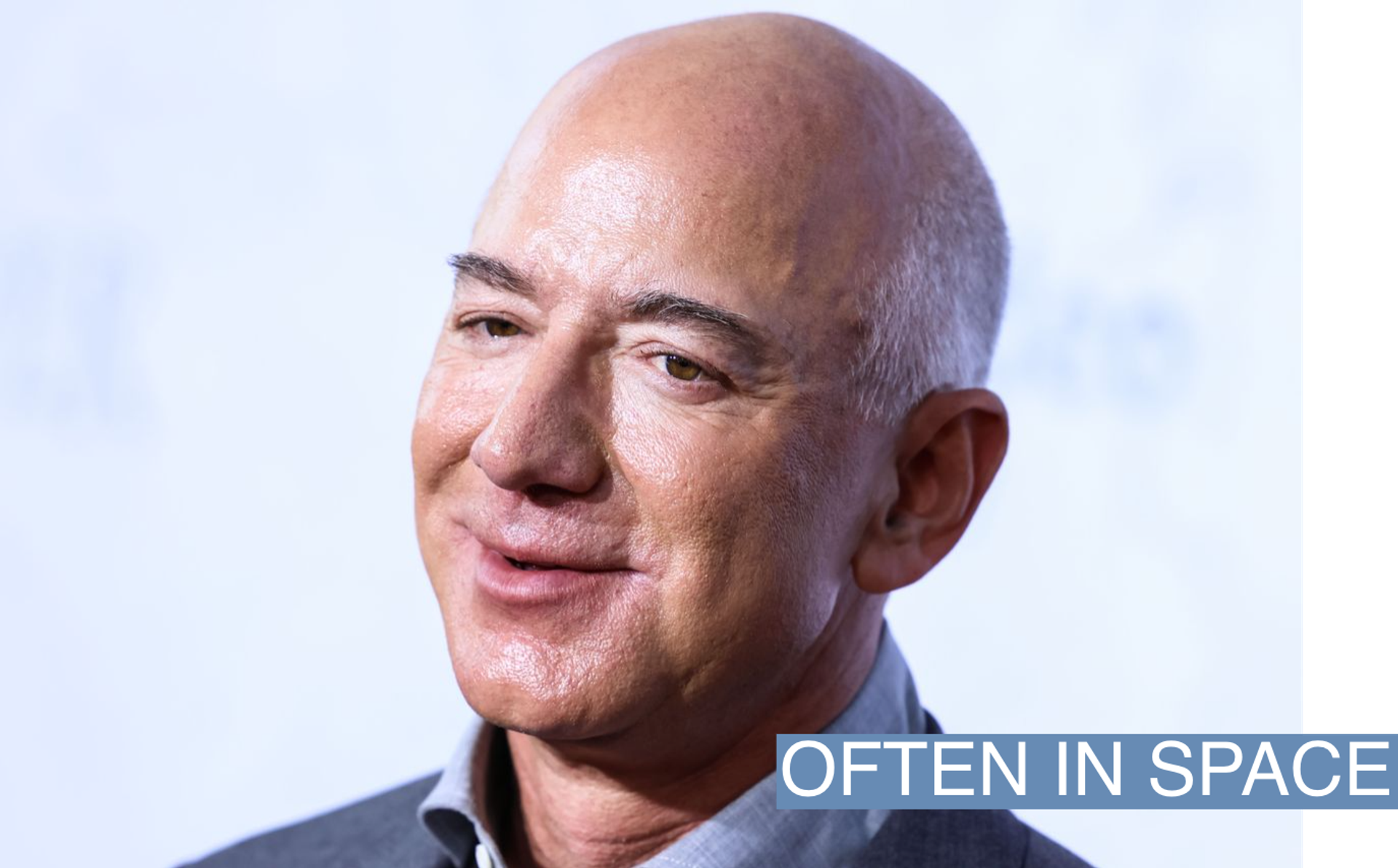

- 2013: Amazon founder Jeff Bezos bought the Washington Post in 2013 for $250 million

- 2014: eBay founder Pierre Omidyar granted First Look Media, including The Intercept, $250 million

- 2017: Apple billionaire Laurene Powell Jobs bought 70% of The Atlantic in a deal valuing the company at about $160 million, according to a person close to the deal

- 2018: Biotech billionaire Dr. Patrick Soon-Shiong bought assets including the Los Angeles Times for $500 million

- 2018: Salesforce Founder Marc Benioff bought Time for $190 million

The new owners promised both to support the journalism and help revolutionize business models.

The billionaires have mostly kept half of that promise, protecting journalists’ jobs and meddling little. But the other half of the plan — to find new models — has remained largely unfulfilled, as the money-losing outlets all continue to rely on their owners’ goodwill for survival, according to people at each outlet. And now all face questions of strategy and morale that are the flip side of dependence on a wealthy benefactor.

In this article:

Ben’s view

To be a billionaire is to be immune from failure in any normal sense.

So it can be difficult to judge the outcomes of these acquisitions, except by comparison.

The clearest struggles are at the Washington Post, which effectively admitted defeat last year in its attempts to rebuild its core as a scalable tech business with products called Zeus and Arc. Now it’s simply a media company that battled The New York Times for Trump scoops but has no answer to its rival’s success in other areas, such as cooking, audio, and games. Bezos visited last week to calm a restive newsroom.

The others follow a similar,if less publicly painful, pattern. The Los Angeles Times has rebuilt its newsroom and improved its local lifestyle coverage, but its strategy remains adrift under Soon-Shiong, who has taken the title of “Executive Chairman” and has not appointed a CEO.

Time has morphed into a global events business with a studio that, I’m told, accounts for about a third of its revenue, and which hopes to break even this year. It’s gradually converting its print product to a US News-style compendium of lists. But it has struggled for relevance in national news — it ranks 43rd in Memeorandum’s analysis of presence in the political conversation, and in December had just over a third of the traffic of another shaky brand of its era, Newsweek, according to Comscore.

Two journalists said they were relieved when editor-in-chief Edward Felsenthal, who had been the company’s CEO since Benioff acquired it, returned full-time to the newsroom late last year.

Omidyar is the only one of the group so far to exit the business entirely. He bet on a fantasy that a movie studio would subsidize his news business at First Look, but finally gave up and this year — with the support of the journalists at the Intercept — cut the outsidery news organization loose and handed it over to its general counsel, David Bralow and editor, Roger Hodge, as an independent nonprofit.

“I’m guessing that it’s proven difficult for them all because it is the sort of business that needs and deserves full attention,” said Craigslist founder Craig Newmark, a tycoon who has given much of his wealth to journalistic causes, including nonprofit local news organizations and reporters’ security. Newmark said he had never seriously considered taking over a media company himself. “People in business who don’t know anything about media might perceive it as easy — in that case they just haven’t done their homework.”

The challenge is in part that during the period when the billionaires emerged as white knights, alternate models seemed hopeless, with print in ruins and the promise of social media collapsing. (I was the editor-in-chief of BuzzFeed News at the time, and we too dreamed of a billionaire savior.)

But since then, distinct models have emerged. Local nonprofits have begun to serve some of the functions of accountability and state government news from Sacramento to Mississippi, seeking billionaires’ — and the other 99.99%’s — money, but little else. The emergence of digital subscriptions gave organizations from the Times to tiny Substacks a stable source of revenue, provided they could connect intensely with an audience. Washington proved a fruitful starting point for a new generation of companies including Politico, Axios, and Punchbowl News. (Semafor is riding some of the same currents.)

Survival without a billionaire requires the kind of obsessive execution and low-key panic that Benioff, Bezos, Omidyar, and Soon-Shiong brought to the early days of the companies that made them rich. Now they own the only news organizations that aren’t running scared.

“Everyone thought the billionaires could save us — clearly, they’re not engaged,” grumbled one executive at a billionaire-owned newsroom. “It’s not a good model because they lose interest or they get pissy.”

Building — or reinventing — a brand in the shadow of a billionaire has its challenges, too. Benioff was the only one of the group to attend the World Economic Forum in Davos last week, a place where, as CNBC’s Joe Kiernan groused, billionaires tell millionaires what regular people think.

Time was the beneficiary of his second-hottest party in the Swiss ski town, a Monday evening affair that didn’t rival the week’s hottest ticket, the Thursday night Salesforce party, with surprise guest The Pretenders.

Benioff said in a text message that he’s committed to the media outlet. “We just had a great Davos with Time,” he said.

Room for Disagreement

The exception that proves, or maybe discredits, the argument I’m making is The Atlantic, which spent its way into becoming a clear rival to The New Yorker for the first time since Conde Nast was alive. Laurene Powell Jobs has done that by spending heavily on journalism without any particular pretense of re-inventing the business of news. She is said to be unworried that The Atlantic is now losing money on nearly 900,000 subscriptions, and excited about a side-project run by her CEO, Nick Thompson, a Twitter rival called Narwhal.

“Laurene loves our journalists and our journalism. We’re very lucky, because it all has to start with deep enthusiasm for the work and for the people, and with a genuine belief that stewardship of a 165-year-old American institution is a hugely important generational responsibility,” said its editor-in-chief Jeffrey Goldberg, who added that Powell Jobs “wants a highest-quality Atlantic that is profitable, constantly growing, and that truly serves the reader.”

The View From INDIA

The US moguls, have so far, kept their regulatory interests out of the newsroom, but the world is full of cautionary tales. One of the richest men in India, Gautam Adani, took control of a crucial outlet for independent journalism, NDTV, last year.

“How can a channel, bought by a corporat[ion] whose success is seen to be linked to contracts granted by the government, now criticise the government?,” said one of its best-known broadcasters, Ravish Kumar. “It was clear to me I had to quit.”