The News

A new generation of African solar power entrepreneurs is finding ways to work around the market barriers — including high capital costs, gun-shy banks, and faltering utilities — that have prevented the sun-drenched continent from embracing its most obvious solution to energy poverty.

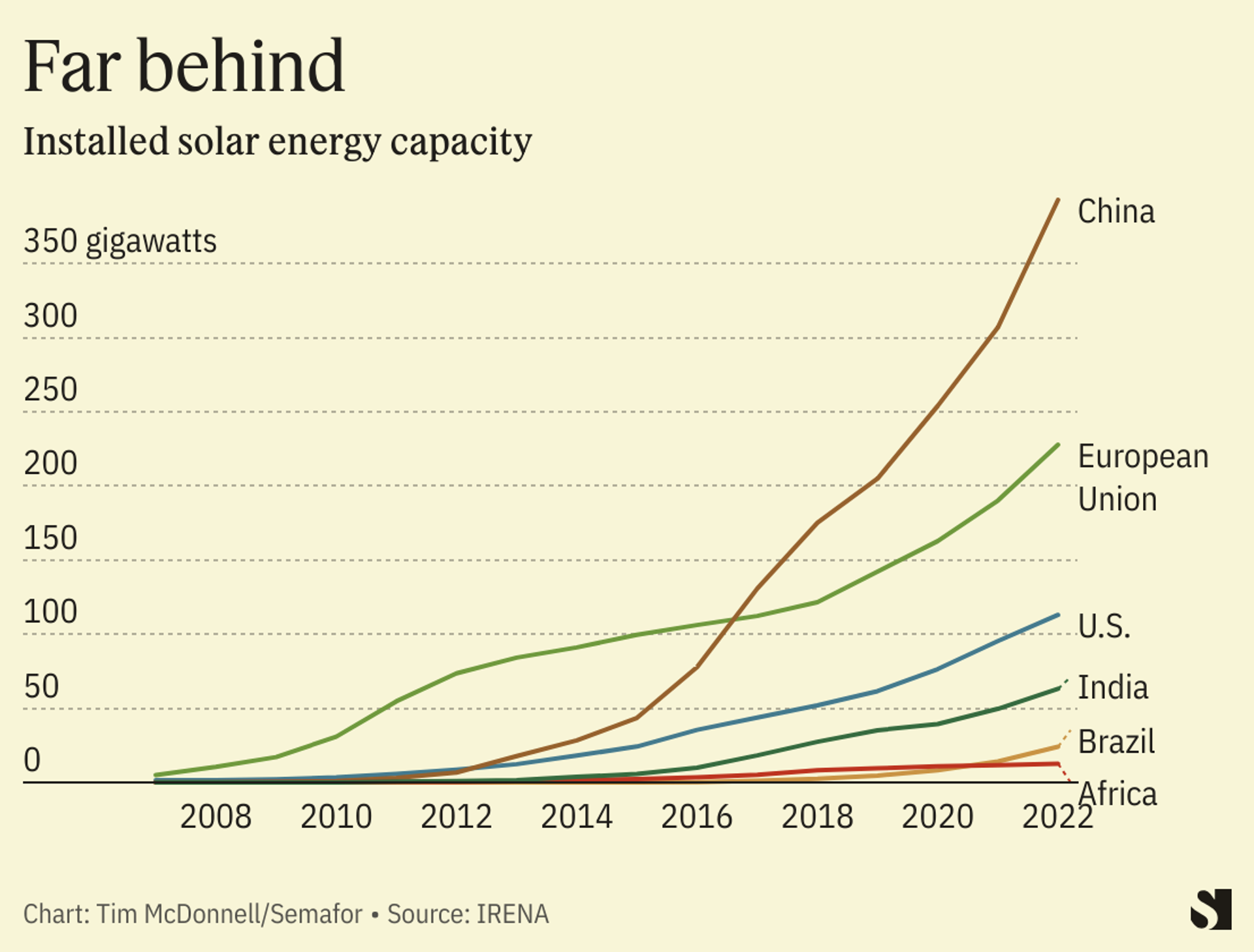

While solar adoption is soaring in wealthier regions, it remains startlingly low in Africa. As of 2022, only about 13 gigawatts of solar capacity had been installed across the entire continent, a tenth of U.S. capacity and nearly 10 times less than what China installed in that year alone. Of that amount, two-thirds is concentrated in just three of the richest countries: South Africa, Egypt, and Morocco. The region’s solar shortfall is a missed opportunity to solve not only its small carbon footprint, but also the fact that half the population remains without any access to electricity at all. And for those that have access, it tends to be expensive and unreliable. But as the cost of solar panels reaches record lows, companies are experimenting with new financial models that could finally turn the situation around. That includes AI-enabled fintech, development bank-assisted utility reform, and old-fashioned M&A.

Tim’s view

For African countries, the biggest obstacle to building out the solar industry is that the financing tricks used in China, Europe, and the U.S. to clear the way for widespread solar adoption — government subsidies and utility payments to solar-equipped customers — can’t work in places where states, utilities, and households are all chronically strapped for cash. At the same time, supply chain problems and the widespread perception by financial institutions that investments in Africa are high-risk mean that the cost of solar is far higher than in other places — the same solar system costs twice as much in Ghana as in the U.S. Bringing down the cost of capital requires a stronger track record of profitable investments than what the industry has been able to show so far. That means new business models are needed to make solar affordable for a broader base of customers.

The View From South Africa

South Africa’s perennial blackouts — the product of aging, mismanaged grids and coal-fired power plants — are driving a rush to rooftop solar. Retail banks that were previously averse to writing loans for solar projects are now setting aside a lot of money to do so, said Tim Ohlsen, co-founder of Johannesburg fintech startup Hohm Energy. But the gold-rush mentality around solar has launched a cottage industry of ad-hoc, mom-and-pop installation companies that have earned a reputation for shoddy work. As a result, Ohlsen said, banks require a mountain of paperwork for solar loans that can make a loan as cumbersome as getting a mortgage: “There’s a lot of unnecessary friction in the system.”

Hohm, which last week closed an $8 million seed fundraising round, spotted an opportunity in smoothing some of that friction. The company uses AI-based design software to plan rooftop solar projects for its clients, and then streamlines the loan paperwork and connects the homeowners to lenders. To set the lenders at ease, the company also keeps tabs on construction and will intervene with installers that do poor-quality work. Last year, the company processed 13,000 applications. “We’re a software business when everyone else in the space today is still very much a hardware construction company,” Ohlsen said. Hohm is now developing a new financial service that will allow low-income households to have solar installed on a lease-to-own basis, essentially replacing their monthly electric bill with a lower payment to a solar company.

The View From Madagascar

For Groupe Filatex, the largest private power producer in Madagascar, scaling up solar has meant re-engineering the company’s relationship with its main customer, the national electric utility. Hasnaine Yavarhoussen, the company’s CEO, set out in 2019 to supplement some of its traditional power plants, which run on expensive, highly polluting heavy fuel oil, with large-scale solar. But financing for the project proved difficult — a commitment by the utility to buy power from him was worth little because the utilities’ own finances were so troubled.

Yavarhoussen was eventually able to raise enough capital for an initial small solar installation, which replaced 10% of the company’s heavy fuel consumption. But to reach his longer-term goal to cut fuel consumption by 80%, he needed help from the World Bank. The bank is working on reforms at the utility that should improve its credit rating, which should in turn make it easier for Filatex to get loans. Yavarhoussen is also working to expand his customer base, by building solar panels at an industrial manufacturing center the company operates and selling the power to the companies that lease space there. Solar farms that can sell power on-site have the advantage of avoiding the costs and complications of the grid. Yavarhoussen’s advice for other power project developers in Africa looking to break into solar farms is to start small, even if the returns on the first project aren’t ideal: “If you can demonstrate real impact with a small phase, then it’s hard for the utility, the government, or the World Bank to not support you.”

The View From Rwanda

Yariv Cohen sees the biggest opportunities in the smallest market: Remote, off-grid villages, where even a solar panel small enough to power just a few lights and phone chargers can have a huge impact on residents’ quality of life. His company, Ignite, is one of the continent’s top retailers of small-scale solar and has sold panels on a $1-per-month subscription basis in 15,000 villages across eight countries. Africa’s small-scale solar industry is crowded with companies like Ignite, but the costs of distributing and maintaining a “last-mile” solar network are high. The only way to make it pencil out, Cohen said, is to reach the scale of selling at least 50,000 systems per year. Ignite is on a spree of acquisitions, snapping up smaller rivals that can’t compete with its scale; it recently bought two solar companies in Kenya, is about to close another in an undisclosed West African country, and is in negotiations on at least six more, he said.

Room for Disagreement

In some cases, development banks are still part of the problem, said Todd Moss, executive director of the Energy for Growth Hub, a nonprofit think tank. Over the last decade, high-profile solar programs led by the International Finance Corporation and U.S. State Department have made little progress on the continent because they have obscured how much they subsidized the projects they worked on. That has left private investors with a warped perspective of how much it should cost to build solar, and driven them away from sensible projects that weren’t quite as cheap to build, per kilowatt-hour, as what the IFC advertised it had accomplished in one-off projects in Zambia, Senegal, and elsewhere.

“There’s no way we’re going to scale clean energy if every contract is tailor-written behind closed doors,” Moss said. “And unfortunately, that’s the status quo in many countries.”